spawning carp

the homeland

I’ve been dropped down here into the metastasized suburban wasteland of Mississauga, where I happened to grow up. Ask anyone who lived in the area 30 or so years ago, and you will likely hear a familiar litany about how beautiful and buccolic this Southern Ontario landscape once was and how post-industrially bleak it now is, having been almost completely tiled over in endlessly repeating fractal undulations of suburban sprawl. Mississauga has become the ultimate edge city, comparable perhaps only to California’s San Fernando valley in the scale of its architectural stultification. Yet there is something touching about this suburban landscape’s role as a kind of failed utopia. As in a new geological epoch, Mississauga’s vanished cornfields, orchards and leafy ravines, are now smothered by a layer of concrete freeway decking and aluminum siding, the new mineral manifestation of the hopes and dreams of its million immigrants, for whom perhaps the very vastness of its banality promises some refuge from a far too turbulent world. Palestinian community centres now stand cheek-to-jowl with Guyanese restaurants and Chinese supermarkets and everyone’s children groove to the thudding beat of hip-hop as they wait on bleak streets for the buses to take them to a *home*, at once everywhere and nowhere.

Mississauga’s *placelessness* is most easily negotiated in an automobile and one feels constantly as if one is inhabiting some massive Yutaka Sone sculpture, for example when hurtling down its (increasingly arteriosclerotic) aorta, the venerable 401, which at one point splays out into 16 lanes, knotting and un-knotting like some kind of dystopian asphalt pasta. The traffic never stops and the 401’s incessant howling penetrates one’s very dreams. The harshness of Mississauga’s blue-white continental sky is attenuated by a fine sepia mist, which hangs everywhere. Composed of particulate rubber, pulverized brake linings and diesel soot, it makes everything look like some post-industrial Canaletto painting, at which someone had thrown a cup of tea.

Of course, I had to get into the Mississauga mood by re-reading j.g. ballard’s Concrete Island, in which the protagonist becomes stranded like Robinson Crusoe on a grassy traffic island, surrounded by freeways that he is unable to cross. While rooting around slobber-space, I came upon Pippa Tandy’s interesting exposition, The DNA of the Present in the Fossil Record of the Cold War(through the imagery of JG Ballard Related sources and Documents in Various Media), on the very cool Sleepy Brain site. Tandy notes that she originally presented this work in Microsoft PowerPoint, which makes it the most brilliant subversion of tedious and dumbed-down business software that I have ever seen.

For a relief from *mall-aria” we drove to the only intact marsh left on Lake Ontario’s heavily developed north shore, which is a tiny yet biologically diverse ecosystem, tucked between the monster homes and mini-malls. Remarkably, it was carp spawning season and dozens of thes ponderous, muscular fish were busily engaged in bouts of noisy, vigorous nuptial thrashing that churned up the marsh’s silty waters in a flash of metallic scales and blood-red fins. The carp themselves are immigrants to these New World waters and displayed such *eagerness to achieve their goal* (the carpish quality most admired by the Japanese) that they seemed oblivious to the rusted out shopping carts and tattered plastic bags littering the cossetting mud of their new found spawning beds.

Of course growing up in suburbia meant that I watched tons of TV, because (let’s face it) there was not much else to do. In fact, my crib was frequently parked up against the television so I could absorb English, which was not my first language. One of my earliest memories is of gazing, through feverish eyes, at the phosphorescence of an early 1960’s, radiation spewing, black and white picture tube that showed an animated image of three pairs of tapping, shoe-clad feet; one of them in a pair of brogues, the kind with numerous little round perforations in the leather. Of course it was the opening credits for the quintessentially saccharine, haute Cold War programme, My Three Sons.. This image was burned into my visual cortex so early, that it has become effectively indelible. The tapping shoes are what I see, when I manage to strip from my mind all other thoughts and images, in deep sleep, in meditation, in fevers. Thee shoes (for better or worse) have become my mantra.

Television was the she-wolf that suckled the spawn of the suburbs, and the opening credits held a particular fascination for us because they marked the transition from one state of *TV mind* to another – full of latent possibility, of narrative as yet untold: “Is it a re-run?” “Which Star Treck or Flintstones episode was it going to be?”, we wondered catatonically as we gazed at the glaring cathode oracle, through the swirling blue smoke haze of our parents’ Craven A Menthols, our bivouacs on the avocado green shag carpet reeking of nicotine and the rye and ginger cocktail sloshings of their boozy weekend afternoons.

Sometimes the opening credits, like oracle bones, could give the keen observer a clue as to what was in store. A case in point was the Dick Van Dyke show, which Super 8mm rebel genius John Porter once beautifully deconstructed in a 3 projecter piece, I saw him screen at Toronto’s (now sadly defunct) Funnel. Each simultaneously projected film contains an endless, carefully archived sequence of all the possible permutations and combinations of Dick Van Dyke’s interaction with the foot stool in the show’s opening sequence, which Porter had obsessively filmed with his Super 8 camera in late night sessions off his television screen. Sometimes Dick trips over the foot stool, sometimes he sidesteps it, sometimes he misses it entirely. Occasionally Porter’s hand enters the frame, pointing to the screen and on the soundtrack warns Dick(?) to “Watch that foot stool!” In its absurd depiction of a TV viewer attempting to affect a show’s outcome, Porter’s film serves as brilliant comment on how, for my generation of Cold War suburbanites, the lives of the ersatz families we watched on television, began in some way to replace our own. In their glibness and relaxed Americanism, this pantheon of electric shadows promised us a way through the landscape of cultural displacement and collapsing consensus that lay under the carbon-copy streets of our treeless neighbourhoods.

I miss the Funnel and all of the hi-jinx that happened there. It is where I first saw the films of tENTATIVELY, a cONVENIENCE and Jack Smith and countless other zealots of the underground. We all made films in those days, usually with thrift store Super 8 cameras and short-dated stock. We would film everything and anything, feverishly splicing together our little ribbons of pictures at late night kitchen tables, and sometimes developing our black and white stock in buckets in our bathtubs, so we could present the following day. The collection of non-sequitorious, *stream of consciousness* movies that I shot in those frenetic days, seem like magic to me now and I will continue posting the occasional digitized still to this weblog.

an old film

Garden Ornaments, Loisaida, NYC

Glass diatom, American Museum of Natural History NYC

Well, here I am, having arrived in the Lower East Side with a *sudden streaming cold*, confirming my long held suspicion that airplanes are toxic metal test tubes, rife with festering disease. So I’ve been spending my time schnuffling around the (once) mean streets in a kind of mucosal delirium, punctuated (thankfully) by moments of sheer Manhattan bliss.

I’ve always had a kind of twisted relationship with this dementedly dense, skyscraper encrusted island, ever since the first time I came here on the day John Lennon was shot, now over 23 years ago. On that day, I beheld a very different city, the gritty old, pre theme-parked New York of graffitied subway trains and an ubiquitous sense of transgressiveness. I must say I share a bit of nostalgia for the lost (old) New York of Lou Reed and Taxi Driver but despite systemic gentrification, the city hasn’t yet seemed to have lost its rampant life force. For a window on how some of the edgier New Yorkers feel about the gradual blanding down of its urban bohemia, check out Bruce Benderson’s fascinating (1994) essay Toward a New Degeneracy.

Ghetto palms, Ailanthus altissima

Bonsai, Brooklyn Botanical Gardens

To me, this city’s protean unstopability is epitomized by its Ailanthus trees, which people here call *ghetto palms*, which seem to erupt from nearly every crack in the concrete continuum, bursting through the pavement of litter-strewn parking lots and jamming themselves up against buildings, defiantly waving their absurdly rampant plume-like leaves in a mockery of human order.

The class war has indeed taken its toll here, but I was pleased to see that some of my favorite Lower East Side guerrilla gardens have managed to survive. In fact these survivors seem to be thriving more than ever, as their caretakers tend them with a new fervor.

Of course being the inveterate botano-phile I had to make an obligatory pilgrimage to the New York Botanical Garden in the Bronx and to the Brooklyn Botanical Garden. These large botanical gardens are veritable Wunderkammern for me, mapping out the vast domains of the botanically possible. At the moment, New York is seething at the cusp of a humid East Coast summer. Every shrub and tree seems to be exploding into flower and leaf at a pace that I find quite unnerving, compared to the more sedate, quietly incremental seasonal transitions of my mossy, drippy West Coast rain forest home.

The New York Botanical Garden has within it an incongruous patch of old deciduous forest along the Bronx River in which grow oaks and tulip trees that have attained great size. We came upon a cross section of a really old tulip tree and of course I had to take a picture to pay homage to Hitchcock’s Vertigo and Chris Marker’s La jetee. Apparently there are a few giant, old growth tulip trees hidden throughout the New York area, broodily biding their time within the city’s overlooked peripheries. The venerable Queens Giant looms over 134 feet high, a stone’s throw from the Long Island Expressway, having miraculously survived close to four centuries of pervasive urbanization.

|

|

tulip tree time travel in the Bronx |

And what would New York be without art? I went to my friend Marina Zurkow’s opening at The Kitchen this week where she showed *Braingirl* (which is webcast on the Kitchen’s site) and her amazing interactive installation, *Little NO*, which is (to quote Marina):

a non-linear allegory with a circular structure, inspired by the Tibetan Buddhist Wheel of Life. In a psychedelic, animated, animal-filled world, a young girl enacts the Wheel’s emotional states of selfhood, through her physical gestures and surreal circumstance

The installation induced in me a wonderful kind of hypnotic synergy in which my mind oscillated between being caught in an endless Powerpuff Girls episode and some kind of demented Tibetan Thangka. The haunting soundtrack made it even more evocative.

The Guggenheim offered up some rather interesting exhibitions, notably Singular Forms Sometimes Repeated which presents a kind of historical survey of of Minimalism, from 1951 till present. Now I have to admit, I have always struggled with appreciating Minimalism which can seem strangely *aura-less*,

adhering to the High Modernist principle that judges an artwork’s validity by its adherence to fundamental properties of its specific medium.

or to quote Frank Stella:

“What you see is what you see.”

Singular Forms Sometimes Repeated largely reinforced this perception with a few *delightful* exceptions such as Wolfgang Leib’s The Five Mountains not to Climb on, exquisite in its vulnerability, being composed entirely of little mounds of hazel tree pollen. A trio of pieces (“Cross”, “Museum piece” and “Star”) by Walter DeMaria, creator of the famous Lightning Field, presented an oddly poignant critique of perhaps the most powerful (and destructive) icons of Western Civilization. The security around some of these *Singular Forms* at times seemed almost ludicrous and for most of the lay public, completely confusing. For example, Jackie Winsor’s (1972) *Sheetrock Piece*, (literally a pile of sheet rock adorned with staples with some square holes cut into it), was zealously defended by its own security guard who constantly admonished the curious throngs to “stand behind the line.” On the other hand, the viewers of Felix Gonzalez Torres’ (1991)Untitled (Public Opinion) (basically an 800 lb pile of neatly wrapped pieces of black rod licorice candy), were encouraged to take pieces of it home with them. For me, the highlight of the show was the most recent work, Damian Hirst’s (2002) Armageddon, which consisted of a thick layer of dead house flies stuck to a large canvas. The effect was beautifully scintillating as the ambient light scattered from the millions of mute metallic blue exoskeletons.

Conceptually more remarkable was the Guggenheim’s exhibition Seeing Double- Emulation in Theory and Practice which poses the interesting question of “Does a computer-based artwork remain the same piece, if it is exhibited on a more recent platform?” While, frankly, I personally haven’t lost a lot of sleep over this issue, it has become a serious concern, given the rapid pace of technological development. A case in point, is Mary Flanagan’s [phage], which mines data from the user’s hard drive, mixing HTML with e-mail, images, help files etc. and displays them slowly and randomly across a blank screen. Now, if the work is shown on a late model computer, it runs too quickly and isn’t as beautiful as in its original version, but if the work’s *code* has to be changed to slow it down, *is it still the same?* Seeing Double exhibits [phage]’s varying incarnations (Windows 98, Windows XP, Windows emulator on Mac OSX) along with similarly phylogenetic displays of other computer artists’ work, allowing viewers to explore this issue first hand. Once again, much of the work left me feeling a bit *aura-deprived* in its complete absence of materiality or sense of the personality of the maker, but also very much in awe of the cleverness apparent in both concept and execution.

The Whitney Biennial was on the other hand, for the most part *stultifyingly bad* with the exception of brilliant drawings by Amy Cutler, Zac Smith, Ernesto Caivano, as well as some beautiful offerings by old war horses, David Hockney and Robert Longo.

But despite all of the art and cultural foment, at the end of a long and sweltering Manhattan day, I remain most enchanted by the giant elm trees in Tompkins Square Park. Their enormous vaulted, umbrella-shaped canopies shimmer golden green in the evening sun, bring me back to distant memories of long vanished childhood summers. I remember gazing up into the crowns of similar elms , (it seems an eternity ago), as I lay on my back in Toronto’s cool suburban grass and watched orange orioles flitting through the leaves. Sadly, Tompkins Square’s stately elms are relics of an extirpitated race. The elms of my childhood are no more, wiped out by an apocalypse of Dutch Elm disease , which has left the eastern North American landscape studded with their mute skeletons.

|

|

Tompkins Square Park Elm Trees |

Sequoia scene in La Jetée (1962)

– an homage to Hitchcock’s Vertigo (1958)

They walk. They look at the trunk of a sequoia tree covered with historical dates. She pronounces an English name he doesn’t understand. As in a dream, he shows her a point beyond the tree and hears himself say, “this is where I come from,” and falls back exhausted. Chris Marker La Jetée 1962

Counting the growth rings of a tree allows us to cycle backwards through time. If a tree is old enough we can travel further and further backward beyond our own time, until we are in a place of imagined memory.

The great conifers of North America’s west coast have become icons of time and sadly of modernity’s fascination and loathing of beings that might outlive us. Perhaps we think that by cutting the oldest trees down, we can somehow stop time and by putting their mute stumps in our museums, assert our dominance over it. What is such a tree after all but a very large, very slow clock, inexorably marking off each passing year with a new ring? For some, it might be too much to contemplate that one day the time of our own death will be fixed – just another spot in an expanding continuum of cells, within the trunk of some giant, whispering evergreen.

Hitchcock uses the sequoia tree as a trope for memory in his (1958) Vertigo. Mackenzie Wark, in his fascinating essay on vectoral cinema, asserts that in Vertigo,

the sequoia tree is to time what moving pictures are to space.

Wark goes on to describe:

In one of Hitchcock’s strangest scenes, Kim Novak, who is playing Judy, who is playing Madeleine, who is playing Carlotta, looks at the cross section of an ancient sequoia tree and pinpoints the rings in the wood when she, Carlotta, was born and died. These trees, she says, are “the oldest living things”. Scotty, played by James Stewart, explains their name. It means, “always green, ever living.” “I don’t like it”, retorts Madeleine, or maybe Judy. “Why?” Scotty asks. “Knowing I have to die”, says Judy, as Madeleine, possessed by the dead Carlotta. Or maybe its Kim Novak who says this. Or maybe Hitchcock.

Chris Marker riffs on Vertigo in his amazing (1962) film La Jetée in which the protagonist actually travels *backwards and forwards* through time from a post apocalyptic Paris “rotten with radioactivity” and at one point, poignantly tries to use a sequoia’s cross section to explain to the love of his *past* life, his achingly tragic *chronosthesia*

Sadly, filmmakers have been trying to remake Marker’s magic and essentially unrepeatable film again and again and they inevitably fail, the fragile aura somehow evaporating under the glare of transparent intentions. A case in point is Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, the latest Jim Carrey vehicle. While competently acted, it is kind of *dumb*, not in an absolute sense, as it is in fact quite cerebral by Hollywood standards, but *dumber* than La Jetée, on which it seems quite clearly to have been based. In Spotless Mind both protagonists opt to have the memories of their love affair artificially erased. At the last minute, the Jim Carrey character has a change of heart and tries to abort the procedure from within his own subconscious. The result is a rapid race though his own memory, in which he literally tries to outrun the neural evaporation of his recent past. Spotless Mind’s borrows heavily from La Jetee’s notion of the emergence subterranean, gray market neural re-programming services, allowing the protagonist with his deep and overriding sense of anomie, to journey back in time and memory to reconcile a lost relationship. But Spotless Mind is a much less elegiac and more manic kind of film, irreconcilably freighted with ego and lacking the cool post-apocalyptic resignation of La Jetee. It almost seems that director Michael Gondry may have somehow erased his own memory of having seen Marker’s film. At least Terry Gilliam cops to the source material in his (1995) 12 Monkeys . Here Bruce Willis is sent back through time to stop the outbreak of a catastrophic pandemic and winds up being put in a mental hospital when he realizes he has been sent back slightly too far. The problem with this film is (well) Bruce Willis, but Gilliam’s overt, (albeit slightly ham-fisted) homage to La Jetée, at least seems to have steered audiences to seek out the original. And, most disappointingly for me, both Gilliam or Gondry fail to cast the venerable sequoia. Of course the sequoia itself has a way of burrowing itself into my subconscious. The saddest sequoia I ever encountered, was housed in a peculiar, dusty old private museum on the Canadian side of Niagara Falls. Instead of historical dates, the massive stump was completely covered with the *business cards* of museum visitors, many of them disgustingly affixed with wads of used chewing gum. It’s a tragic image that I have never quite gotten out of my head. . . Was it the last shrine to Capitalism? In a perhaps futile gesture of atonement for my species, I recently planted a couple of sequoia saplings in the rain forest outside my house, albeit well north of their Californian home. They seem to be growing quite lustily and one can only hope they will in the fullness of time be allowed to gain the girth of their ancient brethren, perhaps to enthrall some future, more enlightened generation, able to appreciate them in life rather than in death.

sequoia stump, gum and business cards

-Niagara Falls Museum circa 1989

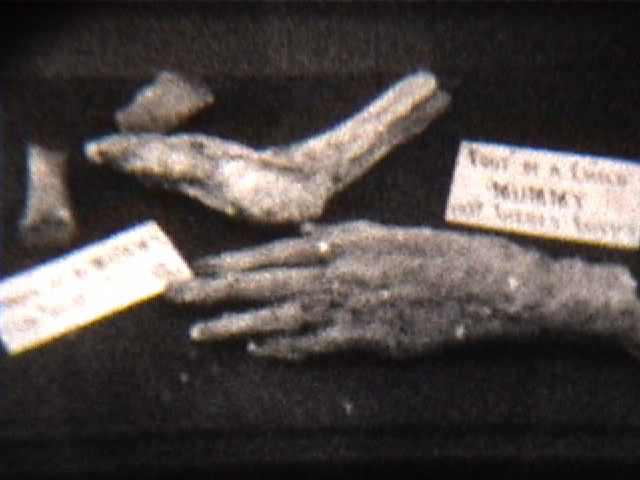

The same museum had some other equally horrific displays which where at once fascinating and deeply disturbing. There was, for example, a complete skeleton of the now largely extirpitated Atlantic Right Whale, on which every bone had been covered with graffiti. I had with me a small super 8mm camera, which I had purchased at a thrift store, loaded with about 3 minutes worth of film. I tried to capture all of the demented images, wildly panning through the exhibit halls, to prove to myself that I wasn’t dreaming, and somehow to later understand what I had just seen. The resulting, haunting, individual frames of black and white movie film, are all that remain for me of this brief visit. I had the overriding (and as it later turned out *correct* sense) that this old museum wouldn’t last much longer, itself a relic of a vanished age. Among the dusty vitrines lay a remarkable collection of Egyptian and aboriginal North American mummies, which apparently been at one time been commonly offered for sale as freak show curios. Perhaps because of the decades of indignity to which they had been subjected, the mummies, gave off a palpable, strangely beautiful aura of anger. One of them had a mouth fixed in the rictus of a scream which no doubt could be heard through all eternity.

Display of mummies

– Niagara Falls Museum, circa 1989

An equal right to anger should be accorded the ancient bristlecone pine, probably *the oldest tree on earth*, which an intrepid and apparently guileless scientist recently cut down to *see how old it was*. PBS ran a documentary about these ancient trees ( at least the ones that are left), the locations of which have now thankfully now been largely made secret, to prevent further such acts of ad hoc public edification. PBS’s accompanying website has a nice VR panorama of the bristlecones *in situ*, whiling away the aeons in their bleak windswept alpine saddles, dreading perhaps most of all not the blast of storms or the heat of the withering sun, but the sound of an intrepid scientist scrabbling up the mountain. . .

Other *old* things to have caught my eye recently was this report on earth’s earliest wildfires, dating back to the Silurian era, barely after the appearance of the first terrestrial plants and just after the second most devastating mass extinction event in earth’s history, which had wiped out 60% of all marine species, planet wide. Apparently, scientists discovered some impossibly old charcoal, which formed even though the atmosphere at that time had significantly less oxygen than does ours today, which meant it was harder for fires to start. Even more fascinatingly, the scientists found a quantity of very old, very charred millipede feces, in the same (er) *deposit.*

Oh, and for those of us worried about the seemingly pervasive rise of Alzheimer’s disease in the *old* and the not-so-old, a recent book, Dying for a Hamburger, draws some interesting links between the occurence of Alzheimer’s and the practice of *batch processing* beef. CBC’s The Current, ran an interesting interview recently with the book’s author, Toronto coroner Dr. Murray Waldman, who noted the curious rarity of Alzheimer’s in countries such as India, (where modern factory farming and meat processing practices haven’t yet been systemically implemented), compared to North America and Western Europe, (where they have.)

BTW, I have left the mossy margins of my rainforest island for a short *field* trip and I am on a plane hurtling toward *old* New York right now, and (provided we miss any tall buildings on the way down), I will be blogging from there for the next few weeks.

Stay tuned . . .

Mummified hands and feet of a child, Niagara Falls Museum, circa 1989