Fire scarred Douglas Fir

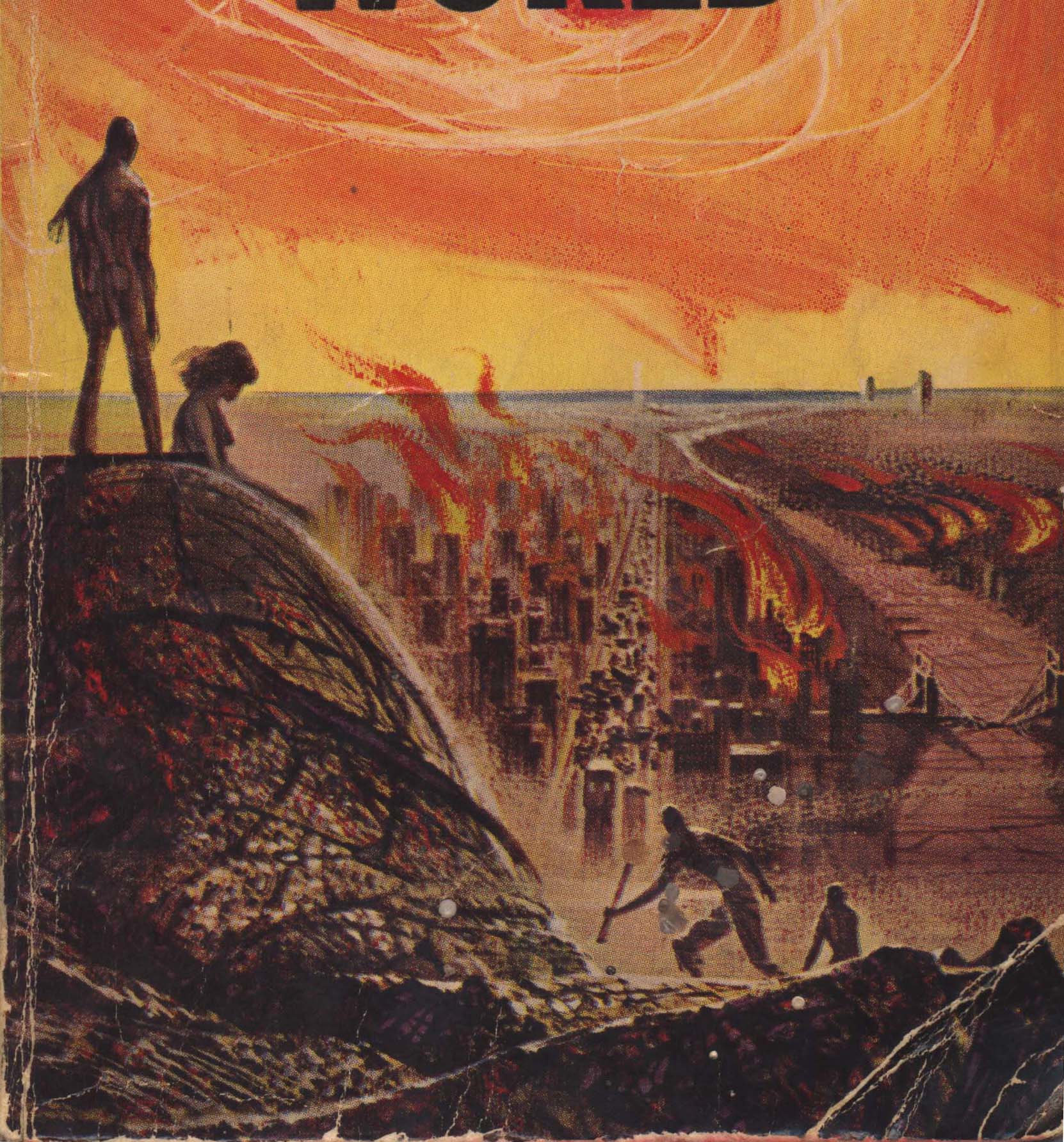

Cover art from “Burning World”

Opuntia cactus, Mittlenatch Island, BC

Fifteen minutes of insipid rain has come and gone, as if to tease the parched grasses, shriveled mosses and cracked earth. It was a tiny punctuation to a relentless and roastingly radioactive marathon of sun.

There has been a palpable feeling of *imminence* for the past two months, as the hot winds blast through the scorched conifers, ready to fan the slightest wayward spark into catastrophic conflagration. Twice in the past week, earthquakes have rumbled along the great seam that joins us to the Pacific’s tectonic plate, as if to remind us we could be heaved from the earth into the roiling seas at a moment’s notice. Scores of snakes lie crushed to death, their last anguished writhings baked into the bubbling asphalt of the melting roads. Fifty-year old Douglas fir trees are turning brown and dying under the nuclear furnace of this unstoppable hyper-summer. Are we on the brink of epic disaster? We are, according to one expert, withering through the worst drought of the past 400 years.

Perhaps this is a harbinger for a period of Triassic like global dryness, with melted icecaps and vast, dusty burning continents as Ballard imagined in his (1964) Burning World.

“The drought” everyone called it, as day after day after day went by with no rain. All over the world it was still ” the drought,” though the rivers had turned to trickles and the trickles to mud as the earth dried, cracked open, and crumbled into dust. Dust that was at first ankle-deep, then calf-deep, then knee-deep . . .

What would it be like if the Pacific Northwest turned to desert? Will we all, as Ballard suggests, wind up sitting on the roofs of our cars staring out from the smoke of a burning landscape at a vast and bitter sea?

In The Ecology of Fear, Mike Davis describes just such a scenario in his essay, “The Case for Letting Malibu Burn,” where he points out the insanity of siting human habitations in the fire ecologies of Southern California, as evidenced by the disastrous firestorms that occurred there during the 1990’s. Apparently several movie stars, (including Dick Van Dyke) became temporarily homeless during these epic fires. Will global warming make the coast of British Columbia an extension of Davis’ “fire coast”? Only time will tell.

The trouble with rapid climate change is that it will likely lead to a biodiversity meltdown. Most species just can’t adapt quickly enough to the changing conditions and ancient ecosystems such as coastal rainforests will inevitably become impoverished. There are some interesting indications to the contrary, however, as a recent Reuter’s article suggests, that describes the recent colonization of the newly heated up Netherlands by plants from Africa. Perhaps here too, some new hothouse flowers will move in to replace the whispering ferns and cedars. Global warming is sure to usher in a strange and frightening new world. Still as an inveterate botanophile, I have to ask myself, “Can I surf global warming (or to quote Amory Lovins, ‘global weirding’)?” Can I populate my immediate vicinity with plants already adapted to the new climatalogical order, with the aim of maximizing instead of minimizing biodiversity? So far, I’ve had good luck with some of the hardier thermophiles such as Opuntia cacti, which seem to do fine in the increasingly arid conditions of coastal British Columbia’s summers. Other surprising botanical survivors (given the fact that I live at the latitude of Quebec City) include, Eucalyptus, Japanese Camphor tree, Chinese fan palm, Szechuan pepper tree, Paulownia elongata and several magnificent bamboos including my current favourite, the exquisite Himalayan, Yushania anceps, resplendent in it’s featheriness. Still, it is deeply tragic that despite my minute “botanical interventions” the misty, mystic, boreal stateliness of my mossy rainforest home will likely soon crash and burn, reduced to an over lit, melanoma-inducing, aridity with the collapsed trunks of massive conifers, charred and petrified in the heat haze and dust to form the next geological palimpsest. Some years ago, I walked through the blinding heat of eastern Washington’s volcanic scablands and got a glimpse of the future in the Gingko Petrified forest. In this otherworldly landscape, the silicated trunks of fossil trees lay strewn about a barren sagebrush steppe, like the fallen columns of some long abandoned temple to botanical antiquity. Many of the petrified logs were ignominiously encased in welded steel cages, presumably to prevent them from suffering the final indignity of defacement by the Quaternary’s ubiquitous upstart hairless primate. While pondering the ruined and withered landscape of our unmitigated internal combustion addiction, we might take comfort in our amazing ingenuity. The US army has recently invented a type of ration package that can be rehydrated by pissing on it. No need to waste valuable water.

If it ever does start to rain again, I know just who I’d like to hang out with. Paul Stamets has been inoculating the man-made deserts left on our island by industrial logging, with a cocktail of mycorrhizal fungi, which he says will form symbiotic associations with baby trees and make them grow faster Stamets is planting a 1000 year forest, a kind of deep time carbon bank against ecological apocalypse, to be protected in perpetuity by a cage of covenants . Stamets theorizes that mycorhizal fungi form a kind of mycelial Internet, transmitting information and nutrients through great distances beneath the forest floor, connecting the roots of trees, even of different species to create a kind of sentience.

Stametsians inoculating a clearcut

This subterranean inter-connectivity has resulted in the world’s largest organism a 3.5 mile wide honey mushroom growing underneath a dry forest in eastern Oregon, estimated to be over 2,400 years old.

And mushrooms can definitely talk. I remember once, over 20 years ago, crawling through the long dewy grass of a September pasture, on Vancouver Island, searching for elusive psilocybes (pronounced sil-(ah)-ci-bees, according to Stamets). After finally finding one, and consuming it, dozens of others, (and this is the only way to describe it), made themselves *known* to me, having found some direct conduit to my visual cortex, of which I had been previously unaware. It’s almost as if they were saying, “Here I am, Here I am!