The British Museum is astonishing, housing some of humanity’s most culturally significant objects, more than a few of which found their way there under what one might now call dubious circumstances.

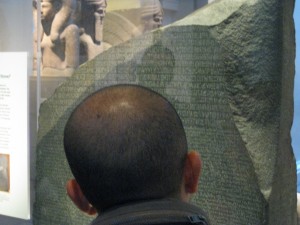

Either through the machinations of a once vast and pervasive empire or more directly through the spoils of war, precious objects converged here in unprecedented quantity, particularly during the 19th century. The Rosetta Stone is a case in point. A dark, dull slab of a thing, it is the museum’s most visited object, not because it is particularly beautiful but because the text inscribed into it was written in three languages – Ancient Egyptian, Demotic and Ancient Greek, which gave scholars a key to decoding the vast compendium of Egyptian hieroglyphs, which they had been badly mistranslated since at least the fifth century. It was re-discovered in Egypt by the French in 1799 but then wrested away to Britain, along with other antiquities, as part of the French Capitulation of Alexandria a few years later.

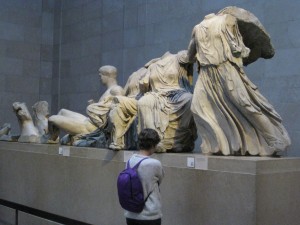

The museum’s acquisition of the so called Parthenon or ‘Elgin’ Marbles, (depending on what side of the fence you are on as to their rightful ownership), has been a source of controversy since their arrival during the first decade of the nineteenth century. They were brought to London by Lord Thomas Elgin, who had them pried from the Parthenon, while Athens was under occupation by the Ottoman Empire, who allegedly issued a permit to him, though this still can’t be entirely corroborated. Lord Elgin, who was there originally there simply to document the Marbles and take plaster casts of them claimed he had to act to save the works from destruction as some sculptures nearby were said to have been burned into lime for construction. In the end, despite shipwrecks, massive personal expense and the initial failure of negotiations with the British Museum to pay for them, the Marbles ended up where they are now and the Greeks have been trying to get them back ever since.

And it is no wonder.

The Marbles are utterly magnificent. Despite their great age (dating from circa 447 – 438 BCE) and the many bits that have fallen off over the intervening millenia, they seem somehow to have transcended both time and material. The British Museum is chock-a-block full of some of the finest examples of stone sculpture mankind has ever produced, yet the Marbles, particularly the figures of the three goddesses from the East Pediment, are in a class by themselves. Their clothing seems to float over the bodies, each muscle, nipple and fold of flesh looking like it might suddenly shift beneath diaphanous cloth that alternately clings and billows in a way that is uncannily and rapturously alive. One has to remind oneself one is looking at cold, hard stone. The dissonance between the obvious materiality and the skill of the artifice creates something truly transcendent.

Despite the endless evil our species has promulgated, the existence of such objects gives me hope. Being in the presence of them, if only for a short while, is a privilege that should be available to all. It is to the credit of the British Museum (and many of the other major London institutions) that they open their doors free of charge. This is something that has always irked me about many museums in North America, particularly those of my native Canada where the collections tend to be pretty mediocre to begin with. To put humanity’s cultural heritage behind a pay-wall entrenches a kind of petty elitism that distances us from the hope and inspiration that cost-free access makes possible. With their focus on admission receipts, too many of our North American museums have slid into the shrill, overly mediated territory of theme park(ism) and ‘edutainment,’ robbing visitors of the simple pleasure of enjoying objects of beauty, antiquity or scientific interest and experiencing them on their own terms.