Sometimes a bad idea just won’t go away. Though Vancouver’s future has been looking a lot greener lately, with the expansion of bike lanes and improved municipal composting, I was dismayed to learn that a city-proposed road expansion is threatening to wipe out Cottonwood Community Gardens, one of the Vancouver’s best-known examples of citizen-initiated urban greening. As a founder of Cottonwood, twenty-one years ago, I have fought this fight before.

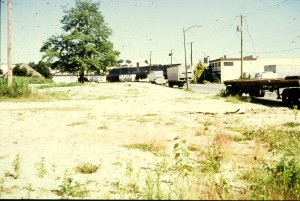

Back in 1991, I started a campaign with a rag-tag group of East Vancouver residents to take over a three acre strip of city land on the southern perimeter of Strathcona Park, which had become a study in urban blight. The city had stopped enforcing anti-dumping bylaws in this industrial neighbourhood and mountains of jettisoned construction debris, landscaping waste, rotten furniture and junked cars were continuing to accumulate on the property with no end in sight, accompanied, unsurprisingly, by an increase in the rat population and the incidence of petty crime.

Tired of this officially sanctioned neglect, our little group of volunteers rolled up its collective sleeves, borrowed some wheelbarrows and shovels and got busy. With an enormous amount of hard work and a sense of community pride, we gradually transformed this unprepossessing piece of urban wasteland into an award-winning public garden and arboretum. It is without doubt one of the things in my life I am most proud of having done.

We called the place ‘Cottonwood Community Gardens’ as a nod to the giant cottonwood trees that tower over its northern edge, their rustling foliage a reminder of the area’s rich ecological past, when it was the marshy edge of False Creek, which once extended as far east as Clark Drive.

When word of our initiative got up to City Hall, we were informed that City Engineering had made plans to turn the dusty lot into a heavy equipment training area, despite being right beside a major park with heavily used playing fields, to which the dust churned up by the machinery would surely have drifted.

But those were the days of ‘recreational apartheid’ in East Vancouver, when the right-wing, Non-Partisan Alliance dominated city council and played favourites with the prosperous areas of the city that voted for them while turning their backs on neighbourhoods (like ours) that didn’t. The NPA dominated Parks Board was at that time busy assembling million dollar beachfront properties for parks in Point Grey and Kitsilano, while neighbourhoods on the East Side had to grovel to get broken teeter-totters replaced in their over-used inner-city playgrounds.

And if that wasn’t enough reason to continue with our intervention, a friendly Vancouver Sun reporter had tipped us off that City Engineering was quietly hatching a plan to build a major new truck route through the nearby Grandview Cut and run it right through this ignominious little property, funneling yet more smoke-belching transport trucks into our already polluted and congested environs.

Clearly City Hall was making some terrible decisions at the expense of the neighbourhood, so we needed to act fast. Whatever automatic legitimacy they may once have had was eroded by the pernicious neglect with which they treated the area, offering it up as a kind of sacrifice zone for their 1950’s vision of a vehicle-dominated city.

The ensuing work was very hard. We pulled out dumpster loads of every kind of disgusting trash imaginable – piles of moldy drywall, engine blocks, bloody syringes, used condoms – even a dead cat in a plastic bag – before we could do much actual gardening. And once we had dealt with all that insalubrious garbage, we hauled in wheelbarrow loads of rotten vegetables, gleaned from the produce warehouses on nearby Malkin Avenue, to make compost to enliven the impoverished soil. To water our initially meager crops, we had to haul buckets from the public washrooms in the park or wait for the rain to eventually fill them.

Yet we persisted, and despite some initial push-back from a few NPA councilors and some grumbling from City Engineering, we managed to prevail and marshaled the considerable public support we had been generating into a long-term lease. This gave us the security and the legitimacy we needed to get some small grants, with which we bought a few tools, installed an irrigation system, a greenhouse and a garden shed. The Environmental Youth Alliance joined our effort and soon started transforming the eastern flank of the property that had been covered in dense, trash-filled thickets, into what would become a thriving centre for youth-focused environmental education.

Gradually but steadily, the sun-baked and squalid expanse of dust and garbage we started out with gave way to groves of exotic trees and carefully tended allotments. The sounds of unfamiliar birds started to fill the morning air and there were cool pockets of shade with benches, where weary passers-by could sit and enjoy the slow resurgence of nature.

Two decades later, Cottonwood Gardens stands out from its surroundings as an oasis of biodiversity, a verdant interruption to an otherwise dreary vista of sterile playing fields and low-rise industrial buildings. A few years into our project, a pair red-tailed hawks built a nest in one of the large cottonwoods only to get evicted, a few seasons later, by a pair of bald eagles that still are there today, their sprawling twig nest and squeaking eaglets adding to the Edenic vibe of the place. I’ve often caught sight of visitors to the garden stopping and staring, incredulously, as these majestic raptors soar over the heat haze that simmers up from the factory roofs and then alight high on one of the cottonwoods to feed their young. It’s just not what you’d expect to see in what was long one of the city’s most deprived and green-space deficient districts, and yet even this is still relatively early in the long process of ecological recovery and one can only wonder what might eventually be possible – if, that is, we are allowed to continue with our long-running experiment in community ecological repair.

The seedlings and saplings we fussed over and watered all those years are now mature trees – a rich variety of them such as the blue-flowered Empress trees I grew from minuscule, milkweed pod-like seeds I picked up from under a gnarled, old specimen that still survives in Thornton Park. There are multiple kinds of mulberries, edible chestnuts, persimmons, Asian pears and groves of rare bamboo, along with extensive plantings of native species; all of them chosen for their ethno-botanical significance to the diverse heritage of the surrounding neighbourhoods.

In their well-tended garden plots, people from all walks of life coax forth a bounty of blooms, fruits and vegetables from what was once sterile rubble, sharing the food and recipes with their friends and neighbours in a living paradigm of what a green, inclusive city is supposed to be. This is an ‘open-source landscape’ that continuously evolves as a function of those who participate in it, with no real need for the top-down ministrations of bureaucrats, engineers and other members of the professional class. Cottonwood has always just run itself, a self-declared ‘autonomous zone,’ which is its true beauty but also makes it a threat to those who have a vested interest in maintaining the traditional power relationships that have controlled the evolution of the city.

Despite some headwinds at the start, Cottonwood has mostly had a cordial relations with civic politicians of all political stripes, and it didn’t take too long for even our foes to realize that the garden, which is essentially self-maintaining, creates environmental benefits and opportunities for community-building far beyond what is possible within the traditional parks system – at almost no cost. Cottonwood has been a very good deal for the city. With the rise of Vision Vancouver and their explicit advocacy of urban agriculture, I thought we were home free. During the last civic election, they even featured Cottonwood on their party web site as a prime example of a successful policy.

Imagine my shock then, when I found out last month that Cottonwood – despite all the accolades, the myriad hours of embodied volunteer energy and the many politicians who have schmoozed with us there, getting their pictures taken with babies and flowers – is once again on the chopping block, threatened by the same road, (though it’s now called a ‘super road’) we fought off all those many years ago. I was doubly surprised to learn that Vision Vancouver was behind the new spin on this same bad, old idea.

So how did we get into this ‘déja vu all over again’ situation?

Over the past year, Mayor Robertson and the rest of the Vision organization have been publicly promoting the removal of the Georgia and Dunsmuir Viaducts, a pair of concrete flyovers that are architectural relics of a proposed downtown freeway that got quashed by public outcry during the 1970’s. Though ridding the city of these monuments to twentieth century car culture might seem like a swell idea, (I got so excited about it, I even proposed to re-purpose them into a Highline style elevated garden), their removal will initiate a cascade of outcomes, not the least of which is that a substantial acreage of valuable real estate, now languishing as parking lots beneath the viaducts’ perpetual shadow, will get ‘day-lighted’ and hence available for development.

The viaducts, though not a freeway as such, do convey a substantial amount of traffic via Prior Street, a busy arterial that runs through the rapidly gentrifying Strathcona neighbourhood. Against the background of the viaducts’ proposed removal, the Strathcona Residents Association initiated a vociferous media campaign to get traffic calmed on Prior, to which the mayor responded with a proposal to build a so-called ‘super street’ that would divert much of Prior’s volume onto a newly widened Malkin Ave, whose right-of-way happens to pass right through the middle of Cottonwood Gardens. So we’re right back where we started from 21 years ago, only this time with a lot more to lose.

It has to be said though, the SRA has some valid arguments about the perils of Prior. It is a fast moving, high volume street with all the attendant traffic casualties, pollution and noise one might expect; hazards it shares with other high volume arterials in the area, where commuter and commercial traffic is routed through residential zones, as is the case with 1st Ave., 12th Ave., and a large section of Knight Street. To add to the complexity, the Province newspaper reported that traffic calming on Prior could add an average of $100,000 to the property values there, a not inconsequential outcome in a neighbourhood where real-estate prices have already skyrocketed.

Though this muddies the waters somewhat, it doesn’t negate the SRA’s safety concerns, but further underscores the need for Vision to step up with a much more innovative solution than the robbing Peter to pay Paul approach they have thus far hinted at, sacrificing Cottonwood, by now one of the city’s best-known ecological landmarks, for the uncertain outcome of traffic re-routing. Even without the Malkin ‘super street,’ the city itself anticipates the removal of the viaducts alone could actually contribute to a moderate decline in vehicles on Prior St.

as today (they) act as a magnet for commuter traffic with some commuters going ‘out of their way’ to access the viaducts via Prior St. With (their) removal, a significant proportion of commuters will naturally redistribute to other routes.

So the entire Prior issue may in fact be a red herring, with no real connection to what happens along Malkin except to add an unwarranted hysteria to the decision making process that plays nicely into the hands of the pro-development lobby.

Along with the local concern about the viaduct removal and its effect on Prior, there is massive pressure being exerted by the federal and provincial governments, who are pushing a multi-billion dollar ‘Pacific Gateway’ program to expedite truck and rail traffic into and out of Vancouver’s port, with the aim of facilitating Canada’s growing trade with the Pacific Rim. The widening of Malkin has already been floated by City Engineering as a desirable way to meet these goals along with an overpass to ease the indignity of traffic jams at the at level crossing on Prior.

While Vision has not yet announced a decision on what they have already christened the ‘Malkin Connector,’ there is a creeping air of inevitability to their public communication on the subject. Mayor Robertson has made it clear he wants to expedite the matter and on a recent CBC ‘Early Edition’ interview, Vision councilor Geoff Meggs showed an alarmingly wishy-washy attitude toward Cottonwood and its future, telling his audience that Malkin has ‘always been seen as a future major arterial’ for ‘improving goods movement, (and that) ‘there will be impacts’ so that ‘the area can be set up properly (emphasis mine) to support jobs and development opportunities.’ These are the chosen words of an individual who has already made up his mind, though Meggs did add, rather noncommittally, the garden will be given ‘serious consideration,’ which is not, on its own, hugely encouraging.

In the end though, what we have here is not so much of a political issue, but a problem of urban design, which therefore should be solvable, if enough creativity and resources are directed at it. A ‘win-win’ outcome here would be a huge boost to Vision’s green credibility and give a clear signal they were serious about moving away from the traffic-centric, development driven, business-as-usual approach to running the city that has been so prevalent in the past.

Conversely, it would be wrong-headed in the extreme for Vision to sacrifice Cottonwood for the sake of a ‘super roadway,’ no matter how highly the engineering department recommended it. Given the by now iconic nature of this garden, I can pretty much guarantee there would be massive protest should it come down to the bulldozers moving in, and the spectre of photogenic young environmentalists and outraged senior citizens chaining themselves to the garden’s greenery to ward off city road-building crews would be death to Vision’s green brand and a gift to the right-wing forces so eager to unseat them.

So Vision had better come up with a solution that lives up to its party name – an imaginative solution that doesn’t pit neighbour against neighbour or trash this beloved oasis of urban nature – for the sake of vehicles. A world-class, ‘green’ city deserves world-class design that is both environmentally and socially at the cutting edge – a standard that may be beyond the tired, old orthodoxies the traffic engineers have had to offer. We can’t let Vision cut corners here, despite mounting pressures on them to do so from some very powerful players. But will they have the foresight and creativity to get this right? There is a lot riding on the outcome. Vision got a substantial mandate on their pledge to make Vancouver ‘the greenest city in the world.’ How they deal with Cottonwood will show us all how committed to their values they truly are. I for one will be watching very closely.

If you’d like to weigh in on this issue and help prevent Vision from making a terrible mistake, here are some links:

‘Save Cottonwood’ Facebook group:

http://www.facebook.com/SaveCottonwoodCommunityGarden

‘Save Cottonwood’ Twitter feed:

https://twitter.com/SaveCottonwood

Geoff Meggs e-mail:

clrmeggs@vancouver.ca

Gregor Robertson e-mail:

gregor.robertson@vancouver.ca

Mayor and Council e-mail:

mayorandcouncil@vancouver.ca

(this isn’t the greatest way to get attention. It’s much more useful to e-mail individual councillors directly)

Here is a link to all the individual City Council contacts:

http://vancouver.ca/your-government/city-councillors.aspx

Also here is a link to my own history of Cottonwood:

http://www.oliverk.org/page/cottonwood-community-gardens