|

|

North Troy NY brownfield savanna

safari into the Williamette Cove brownfields

Those of who call ourselves ‘environmentalists’ have a tendency to imagine a prelapsarian wilderness that once was pristine and then became progressively defiled and diminished through the carelessness of humankind. But the earth had been through many environmental catastrophes long before we came along– though this doesn’t exactly excuse us from our manifold sins. The infamous Chixculub asteroid impact suddenly ended the long reign of the dinosaurs and the more insidious yet equally catastrophic evolution of photosynthesis deep within the cells of certain cyanobacteria contaminated the earth’s early biosphere with oxygen– a fatal poison to the majority of organisms present at the time, resulting in what is now known as the oxygen catastrophe, a mass die-off of the earth’s biodiversity and a climate change event that froze the planet in the longest snowball earth episode in geologic history.

What is unique in the present (Anthropocenic) moment is that we know we are causing a massive and likely suicidal ecological crisis and yet choose not to do anything about it. Here we are at the tail end of 2014 with atmospheric CO2 levels higher than they’ve been for 800,000 years and the 6th mass extinction accelerating to the point where the earth has lost half of its wildlife species in the past 40 years. Political leaders, particularly those of oil rich countries like my native Canada either willfully ignore the scientific consensus or in the most egregious cases, (again Canada), actively censor the findings of scientists and even weather forecasters. Because a little knowledge can be a dangerous thing. Or is it?

In a recent video, Žižek makes the perhaps startling case that there is considerable poetry in our present situation, that is to say, our disavowal, our state of knowing that something is true and yet acting as if it wasn’t. He argues that to “truly love the world, we must love its imperfections,” including, presumably, the ones for which we are directly responsible. “In trash,” he declares “is the true love of the world,” a sentiment similarly observed by a Zen priest in the masterful little documentary, Tokyo Waka, which explores the world of Tokyo’s ubiquitous and trash loving crows. To be more precise the priest observes: “In trash is the residue of desire,” a sentiment perhaps less direct but still elevating garbage to a kind of reified affection.

To follow that logic, when an entire landscape becomes trashed, it should be particularly worthy of our love and it was in this spirit that I embarked upon my summer explorations…

But first some background: The Superfund was originally set up in the America in 1980 to identify and facilitate the cleaning up of the country’s most hazardous waste sites. In theory this might have created sufficient funding and legislative willpower to deal with this dangerous and unhealthy problem but between partisan politics and bureaucratic ineptitude, implementation fell far short of what was needed.

Though most people would want steer clear of toxic wastelands, I wanted to see if there were any adaptive ecological processes operating there that might be transforming these zones of exclusion into useable habitats. I had the strong sense that conventional ecologists and environmentalists might be missing something very important, that nature was capable of doing an end run around our destruction, if only we would get out of the way. My summer safari took me to sites on both sides of the continent–Troy, NY and Portland, Oregon–and what I observed there gave me some hope and insight into nature’s surprising ability to colonize the messes we have left behind.

I was invited to Troy by my pal Kathy High for a collaborative investigation into the area’s extensive brownfields. Once known as the ‘collar city’ for its shirt, collar and textile production, Troy is considered the birthplace (and graveyard?) of the American industrial revolution. A fortuitous confluence of rivers made it possible for early factories to harness abundant mechanical (and eventually hydroelectric) power as well as to cheaply transport products and raw materials. Like so much of America’s industrial heartland, the area has suffered from economic decline and many of its once thrumming factories lie in ruin in within highly contaminated terrain.

Some of the worst sites are situated along the banks of the picturesque Hudson River, which transitions here from tidal to freshwater, the end of a long estuary. Downstream, all of the Hudson is classed as a Superfund site because of extensive contamination by PCBs, a potent carcinogen, dumped for decades by the General Electric Corporation as a byproduct of manufacturing transformers and other electrical components. PCB’s are a persistent organic pollutant (POP) that bioaccumulate in the river’s fish, making many species unsafe to eat–including the reputedly delicious striped bass that spawns nearby at the junction of the Hudson and Mohawk rivers.

chimney swifts over North Troy Despite being a very degraded ecosystem Troy’s former industrial landsa are full of surprises. As part of a summer youth program, I led a ‘bio blitz’ of a community garden that had been established on a brownfield site near the Sanctuary for Independent Media. It wasn’t long before we found a magnificent stag beetle hiding in the rotting stump of an (invasive! exotic!) Ailanthus tree. High overhead, chimney swifts traced their invisible arabesques into the topaz air of the summer evening. This species, has long adapted to human presence and as indicated by its common name, makes its nests in disused chimneys. The chimney swift is a close relative of the Vaux’s swift, which puts up a spectacular display every evening as great clouds of the birds funnel into in a large chimney at the Chapman School in Portland, Oregon.

A local Troy resident told me she had recently found red-backed salamanders under debris in her backyard yard, situated quite near some of city’s most contaminated industrial sites, with nothing that might be deemed ‘intact’ woodland anywhere in the vicinity. With the sharp decline of amphibians worldwide, even in protected national parks, it might seem surprising to find them surviving in such anthropogenically disturbed habitats but this is consistent with findings in the UK where rare newts and other amphibians as well as lizards, slow-worms and grass snakes make their last stands in these unprepossessing environs, among the trash, eroding pavements and ruined buildings. In fact brownfields turn out to be far more suitable habitat for these delicate little creatures than is the intensively managed agricultural landscape that has obliterated large tracts of Europes’s biologically diverse ‘Kulturlandschaft’.

stag beetle in Ailanthus stump At a Superfund site at the foot of Troy’s Ingalls Ave, I watched turkey vultures soar over an edenic looking mosaic of meadowy expanses that have cloaked the heavily contaminated soil. These neo-savannahs are punctuated by lush groves–a botanical mosh pit of weedy natives like box elder, black locust and cottonwood mixed in with exotic Ailanthus and Paulownia. All of this is gloriously unmanaged, left to its own rampancy, and though the species constituting this habitat are largely considered ‘invasive,’ they embody a new kind of ecological becoming, their novel juxtapositionings and processes of succession–a ‘Nature 2.0′ in the making.

If we put aside our purist bias, we might celebrate brownfields as territories of regeneration and marvel at how they adapt to the disturbances and wastes we leave in our wake. One might even regard them as ‘wilderness’ of a certain kind as they are one of the few ecological realms we have let slip from our control–leaving them free to reconfigure themselves and follow independent trajectories of neo-evolution.

Troy NY’s future brownfield rangers The collapse of industry though, leaves more than just picturesque ruins and novel habitat in its wake. For human communities,‘Detroitization’ means decaying infrastructure, diminished economic opportunity and the adverse health effects of pervasive chemical contamination. If sufficiently de-toxified, these lands can be rehabilitated as perfectly reasonable urban nature parks (see my previous posting on Berlin’s Templehof airport) but the challenge is to do so without diminishing their often surprising biodiversity.

Troy might be an ideal location for a Brownfields National Park, where local youth could work as ‘brownfield rangers,’ leading tours of the area’s ecological and historical heritage as well as doing field studies and cataloging the species to be found there. Though this necessitates a change of perspective in what we North Americans typically think of as a ‘natural’ park experience, it is high time we open our minds to such opportunities. Brownfields are the future. Brownfields are us!

Over on the other side of the continent, I met up with artist Marina Zurkow in Portland, Oregon. Together, we led artistic incursions into a Superfund site on the edge of the Williamette River. We explored first by water, using a flotilla of kayaks peopled by an intrepid collection of individuals who responded to our call for participation in what (to the less adventurous) might have seemed an arcane enterprise. We conceived our expedition as a kind of group imagination exercise and christened it -“IF YOU SEE IT–BE IT!” in the spirit of the biosemiotician Jacob Von Uexküll, who did such groundbreaking research on the spatio-temporal worlds of animals, which he termed the ‘Umwelt.’ Aboard our tiny craft, we collectively tried to imagine/channel what it might have been like to navigate the contaminated and disturbed riparian environment from an animal’s point of view (water striders, otters, sturgeons, etc.) – inhabiting (in our mind’s eye) their biosemiotic state, ‘becoming’ them, as it were, in a collective thought exercise.

Marina’s long term plan is to construct a raft-like roving laboratory she calls the Floating Studio for Dark Ecology, on which artists and researchers ply the river, exploring its narratives of contamination and recovery as well as disseminating practices of contemplation and engagement between its human and non-human communities.

Our early evening voyage proved suitably anthropocenic: a bald eagle gliding through the shimmering cottonwoods of Ross Island–a section of river whose bed is being continually scoured by heavy gravel mining machinery–the blue tarp and scrap lumber bricolage of homeless encampments festooning the banks of the Williamette–the third world within the first world, the metabolic waste of neoliberal capitalism as it eats its way through our material reality.

Neo-ecologies of Williamette Cove Once again there were fascinating and new ecological assemblage in these zones of dereliction and abandonment. Washed up on the industrial shore of a former shipyard–exquisite hydrozoans of a type I have never seen before:

hydrozoan The brownfields of the former factory site at Williamette Cove, though dangerously contaminated with heavy metals, wood preservatives and organic pollutants, proved not so ‘brown’ after all and were resplendent with novel botanical groupings–neo-succession! Native species like Arbutus menziesii (Madrone) formed habitat groupings with such hardy exotics as Paulownia tomentosa (princess or empress Tree) and Crataegus monogyna (European hawthorn). It is thought the empress trees made their original landfall in North America via their fluffy seeds, once used as a packing material for porcelain and other fragile goods originating in China and Japan. A gust of wind and an open crate at the dockside and their botanical colonization of the continent would have been begun.

In addition to brownfield neo-ecologies there is a parallel and equally fascinating neo-geology emerging from the material detritus of our age. Mineralogically, these are mostly composites and conglomerates or pyrolized residues of industrial processes such as coke and slag, as well as ceramics that have been fired into the form of brick, tile and pipe, much of it broken up into rubble. This so-called ‘urbanite’ is dominated by concrete and ferro-cement in various states of decay and petrochemically based asphalt and asphalt concrete, widely used in paving.

Sometimes though, a geologic object occurs that is of more obscure though still clearly anthropogenic provenance. At Williamette Cove, we came upon an exquisite specimen–a fossil of sorts–consisting of a fused mass of ribbed metal fragments, the armouring of industrial electrical cable, set within a matrix of a more indeterminate material, which might have been partially incinerated plastic. Perhaps this mystery mineral was formed when some itinerant metal collector tried to salvage copper wire by throwing scrounged cable into a campfire to melt off its rubber insulation and loosen the metal cladding. I may never discover this exquisite object’s true origin and it might well become the topic of frenzied conjecture to some future archeologist, wondering what our experience was like as we drifted deeper into the fraught and turbulent horizon of our anthropocenic future.

neo-geological form

zone of alienation

zone of regeneration

In Tarkovsky’s 1979 film Stalker, a mysterious guide leads a couple of characters known only as ‘the writer’ and the ‘professor’ into a post industrial ‘zone of alienation’ where it is promised one’s innermost wishes can be granted and where the rules of physics no longer apply. The ‘Zone’ is completely abject, a place of weeds, broken machinery and the ruins of factories and yet it is hauntingly beautiful in a way that is triggered (perhaps) by our deep yet unconscious familiarity with such landscapes –the places Walter Benjamin called the optical subconscious, the quotidian zones in which we are so fully at home we don’t even realize we live there.

These aren’t the iconic, aspirational landscapes of snow-capped mountains, palm fringed coral beaches and glittering urban skylines –the stuff of screen savers and photo murals in tacky restaurants, but rather the prosaic localities we continuously experience, perceiving them peripherally, from the corners of our eyes yet rarely explicitly acknowledging. The French term ‘terrain vague’ comes closest to the way these places feel and they might take the form of a trash-strewn railway embankment or an abandoned car park with rank vegetation coming up through the broken pavement or perhaps one of those forlorn, zones of contamination we refer to as brownfields, which have become the global hallmark of industrial decline.

I think back on my Amtrak journeys through the rust belt of America, marvelling at the Piranesian grandeur of once opulent railway stations left to crumble at the trackside, the ruined vaults now sheltering only birds which dart in and out of the shattered arrays of windows. The train keeps chugging lethargically (it is Amtrak after all, itself a symbol of decline in American technological ambition) through dour, neglected expanses, prosaic, ugly, endless –you can’t really call it ‘countryside’ exactly– but for the occasional scruffy woodlot and oily wetland which passes between the wrecking yards, quonset huts and derelict factories. This is (as Deleuze might call it) a ‘striated’ landscape that interleaves the decaying residue of a once prosperous age of material production with a resurgent, weedy nature –an ecology of discard, a ‘zone of alienation’ where anything might appear– a muddy field strewn with bone white shards of dishes and upturned toilet bowls, the twisted wreckage of a carnival rides left over from, what? A tornado? Perhaps, even–though I did not experience it–the fulfillment of one’s deepest wishes…

But is this not the state of the world as we all now know it? It’s the Anthropocene, baby, and collectively we’ve chewed up every inch of biosphere; extirpating, contaminating and cultivating ourselves into this, the global ‘Nature 2.0’ reality, where even the unfolding of weather and the chemistry of the oceans have become extensions, artifacts of human existence. So past the point of no return are we that we might as well discard nostalgic notions of ‘wilderness’ and adopt a new, Anthropocenic grammar, already envisioned by the likes of Žižek and Morton, which more aptly describes the hybridized, pervasively humanized environment in which we now live.

terrain vague Our planet has essentially become one, big ruderal ecology (from the Latin ‘rudus’ meaning rubble), characterized by the large-scale extinction of species–passenger pigeons, big cats, rhinos–as well as entire ecosystems–Madagascar, the Arctic, coral reefs. And yet there is a curious, parallel process of adaptive evolution occurring in the disturbance ecologies and debris fields (called anthromes) we leave in our wake.

At Chernobyl (one of the greatest ecological and social messes we have ever been responsible for, a byword for lethal, irreparable contamination and epic technological failure) some bird species–and by no means all of them, as many kinds there have significantly declined–but certain bird species seem to be surviving by evolving a tendency to produce more cancer-fighting antioxidants which help resist the effects of the pervasive radiation. Scientists are calling this “unnatural selection” and it is already driving evolutionary change.

canid hyperorganism In much of eastern North America, the wolf was largely wiped out during European colonization but it has recently come back not as a wolf exactly, but a kind of hyperorganism–a three way hybrid between wolf, dog and coyote that pushes the boundaries of what it even means to be a species. With the precipitous decline of the ancestral wolf, an ‘eye of the needle’ effect ensued in which wolf genetics became more ‘soluble,’ more open to other singularities and contagions, a necessary precondition for the evolution of a new, protean canid, able to prosper in the niche now available for some canny predator able to exploit the pervasively humanized and ecologically degraded environment of second growth forest and exurban sprawl–the kind of places that are an anathema to the so-called ‘pure’ wolves of the primeval wilderness but which offer abundant prey resources of lawn-fed deer and genetically moronic pets. Enter the ‘Coywolf’ or Eastern coyote. They might be a product of ‘unnatural’ selection, but they sure are hungry!

Such novel recombining is occurring at a multi-species level too, with entirely new hyperecologies evolving as weedy, native species commingle with invasive exotics, all of them jostling and repositioning themselves into configurations that never would have existed ‘naturally’ but which now comprises recognizable and widespread landscapes of brownfield savannah and emergent, wasteland forest that are found throughout the world in pretty much any place we have exploited and then turned our back on. Many of these organisms are the hardy cosmopolitan nomads we are all used to seeing, such as tree of heaven (also known as the ’garbage palm’), black locust, pigeons and rats, but perhaps surprisingly these unprepossessing assemblages can support a diverse array of other species, some exceedingly rare, which hail from habitats like gravelly steam banks and dry heaths now largely obliterated from a hinterland dominated by chemical intensive farming and vast, ecologically sterile acreages of housing developments and big box stores.

In the UK, where humanized landscapes are particularly well studied, it is estimated that up to 15% of the nationally rare insects and spiders are dependent on brownfields for their survival as do several species of reptiles, orchids and other rare plants.

I was delighted last March to visit the grounds of the now disused Templehof Airport in Berlin, which as a result of citizen pressure has been set aside as a kind of publicly accessible ruderal ecology park. Here one is greeted by the incongruous site of windsurfers careening along miles of abandoned runways while skylarks hover high over vast swathes of tawny grassland, singing and establishing territory in their annual rite of spring.

Along with a surprising diversity of meadow dependent birds – wheatears, shrikes, whinchats and so on, 236 bee and wasp species have been recorded on the grounds, more than 40 of them endangered or near extinction, particularly those dependent on the open, sandy microhabitats that have all but vanished in the over-managed environs of the countryside.

gestapo prison excavations

airfield meadows

This wonderful interleaving, this striation, this ‘to-ing and fro-ing’, between architectural ruin and ecological renewal is to my mind a tremendously optimistic model for the future of parks in general and for our appreciation of landscape as a whole and it is in promoting this aesthetic that Berlin is very much at the fore. The Templehof park doesn’t try to paper over its problematic Nazi past but lets us grapple with it by preserving the forbidding Fascist architecture and letting us watch archeological excavations of Gestapo prisons and slave labour camps taking place on on its grounds.

At the same time we are offered profound hope by witnessing innate processes of ecological and cultural regeneration get encouraged, not in an over-planned or commercialized way, but from the ground up, in a way that is distinct from the banal, generic late capitalist aesthetic that so frequently defines urban renewal initiatives elsewhere. By being leaving it alone, Templehof is able to renew itself.

Though the global ecological crisis is deep and inestimably tragic, we can perhaps allow ourselves to cautious celebrate the evolution of a new kind of nature, a ruderal nature, where kestrels soar across the heat haze of abandoned runways that are slowly becoming encrusted with lichens and grasses and where rare wild flowers can find a toehold among the rubble of some of history’s worst crimes against humanity. The sky is filled with the coloured sails of paragliders and a bumblebee is making its first foray into the vast warm vault of another spring.

sailing the runways

skylarks nest here

dwarf birches and tundra  suddenly – reindeer!

The morning broke grey and brooding outside the Kilpisjärvi Biological Station and after a quick breakfast, we were on the trail, hiking up Saana Fjell, guided by Erich Berger of the Finnish Bioart Society. The idea was to familiarize ourselves with the geology, ecology and cultural history of the vicinity so we could dive into our research plans as soon as possible.

The Australian bio-hacker, Oron Catts had already been here for a week to do some scouting for his group’s ‘Journey to the Post-Anthropogenic’ project. They planned to perform a comprehensive bio-archeological survey of the crash site of a German Junkers 88 bomber that came down on Saana in 1942, which included a metagenomic analysis of the plane’s debris field and a recreation of the crash trajectory using a remote-controlled drone.

debris field It wasn’t long before we passed the tree line where the mountain birches gave way to an expanse of open tundra sweeping out before us in a swath of russet heath and exposed rock, with quivering patches of silver cloud here and there snagged on the crenellations of the topography. As if on cue, a small herd of reindeer appeared over the crest of a nearby hill and galloped across our field of view, cocking their heads as they past us and then just as quickly melting into the gloom of the opposite horizon. It is hard to judge distances here in this cold desert. An unusual rock formation in the distance might be small and quite close by or enormous and very far away.

I felt for a moment as if I had been transported back to the Pleistocene, as the landscape I was looking at was what much of Europe and North America would have been like at the end of the last Ice Age, though (other than the reindeer) there wasn’t any of the charismatic megafauna such as the woolly mammoth and the cave lions I would have had to concern myself with back then. Semi-domesticated, reindeer have sustained the local Sami people since ancient times and they are of the few creatures (other than snails) to manufacture the enzyme lichenase, enabling them to survive on lichen during the winter months.

How this delicate ecological balance will be affected by climate change is unclear but to my mind it doesn’t look good. Lichens exist in fairly specific temperature and humidity conditions and in Kilpisjärvi many are symbiotic with the birch trees, themselves a cold-dependent species. A continued warming trend in this region is bound to mean diminishment of suitable reindeer habitat. This has already occurred in North America, where the closely related Woodland Caribou has steadily disappeared from the southern portions of its range.

Standing in the middle of this iconic subarctic landscape, it is hard to imagine rapid changes occurring. For thousands of years, the processes shaping it have been gradual and incremental – the slow scouring of glaciers advancing and retreating, the infiltration of frost with its insidious heaving and splitting, the seasonal flows of meltwater into the lakes and rivers. The cold accentuates the sense of Deep Time here. Rocks dragged by ancient ice flows sit solemnly in place as if they stopped moving only yesterday. The sparse, slow growing vegetation is no match for the overwhelmingly geologic feeling of the place. Even minor disturbances stay visible for centuries.

But add even a small degree of warming and there would be potentially huge changes. Vegetative growth would ramp up, allowing trees to flourish in areas that were once windswept barrens. It is easy to imagine the slopes of Saana darkening as the Scotch Pine (Pinus sylvestris), now found only intermittently in the Kilpisjärvi area but quite common further south, finds conditions more suitable to it and becomes a dominant species. True tundra and the flora and fauna that depend on it could disappear from the area entirely.

lone Scots pine Fast-forward a little further and there could be a whole host of new species that find the once frigid environs of Kilpisjärvi newly tolerable. A good many of these are likely to be weeds, which thrive on man-made disturbance. Investigating the grounds around the research station, I soon found a small clump of English plantain (Plantago major) a cosmopolitan weed, dubbed the ‘white man’s footprint’ by North American First Nations, who noticed it growing wherever European colonizers had disturbed the original ecosystem. The humble plantain is just the beginning. I predict that larger weed species will soon be gaining a foothold at Kilpisjärvi; their seeds imported on tire treads or blown in with the wind.

I wondered how it might look here when Ailanthus altissima, a tree variously known as the ‘Ghetto Palm’ or ‘Tree of Heaven,’ moves into the Finnish subarctic. Originally from China, Ailanthus is exuberantly invasive, and has already moved into ruderal (ruin) ecologies throughout the world without any signs of stopping. This tree has the astounding ability to feed off concrete, allowing it to thrive in cracks in pavement, the roofs and facades of under-maintained buildings and pretty much any other place its myriad seeds are able to lodge themselves long enough to germinate.

Ailanthus trees As the global south becomes uninhabitable due to increasing drought, wildfire and relentless heat, it isn’t hard to imagine a newly temperate Kilpisjärvi becoming a major magnet for climate refugees, human and non-human. Higher annual temperatures, as well as attracting different flora and fauna, could make the cultivation of cereal crops a possibility and perhaps other kinds of intensive agriculture, now more characteristic of Central Europe. This could transform the wild, transhumance landscape into a ‘Kulturlandschaft,’ the subarctic wilderness giving way to ploughed fields, perhaps even orchards. There might be a property boom as the open range lands once suitable only for reindeer husbandry become hosts to cash crops and housing estates. The effect on the traditional Sami lifestyle would be incalculable.

A climate-changed Kilpisjärvi would be a kind of ‘hyperecology’– a co-mingling of adaptive, cosmopolitan weeds, perhaps a few resilient local organisms and a steady in-migration of biota from the south. Outside the national parks and reserves, post-climate change nature will have even less of a free hand. There is massive industrial development afoot for Lapland, particularly mining and its ancillary industries which threaten to blight vast tracts of the relatively pristine landscape with open pit mines, tailings ponds and processing infrastructure, which, as well as inevitably introducing all sorts of pollution will create a new terrain vague of slag heaps and factory wastelands. These ‘brownfields,’ ubiquitous in much of the industrialized world are the preferred habitats of the globally distributed ragamuffin flora: Ailanthus, Buddlea and Robinia, which find the toxic and impoverished soils to their liking.

Industrialized, intensely cultivated and densely populated, the Kilpisjärvi of the not-to-distant future might look strangely familiar to any present day resident of a more temperate latitude. Yet what has been predictable there for so long will soon become much more extreme. We may all find ourselves moving north.

But climate change isn’t likely to stop at this arbitrary point. The heat will likely continue to build, especially if mankind continues dumping carbon into the atmosphere and particularly if the much feared ‘runaway greenhouse’ effect kicks in. What then for Kilpisjärvi? The Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum that happened some 55 million years ago gives us a clue. In those days, the weather north of the Arctic circle was sultry and humid the year round. In addition to the Sciadopitys trees I described in my previous posting, vast swamp forests of Metasequoia and Taxodium spread out across the far north of Eurasia and North America, with turtles and crocodiles plying through the black water and mire. It would have resembled the bayou country of Louisiana or subtropical China, with snow and ice pretty much non-existent, a far cry from the frigid Kilpisjärvi of today, which can be icebound 200 days a year.

Eocene landscape Northern regions are well on track for a repeat of these subtropical conditions according to the most agreed upon climate change models, which predict an up to 4 degree Celsius rise globally by the end of the century, with a strong likelihood that changes in high latitudes will be more extreme. Though the biota will surely be more impoverished than it was in the Eocene, not having had anywhere near as much time to evolve, an anthropogenically tropical Lapland would be a mind-boggling yet disturbingly real possibility.

Though our species’ effect on climate can (and will) precipitate far-reaching changes in areas like Kilpisjärvi, there are many planetary processes playing out over which we have no control. The evolution of biota over Deep Time is as much happenstance as forward movement, with periods of great flourishing such as the infamous ‘Cambrian Explosion’ interspersed with ‘reversal’ or mass extinction, either organically or extraterrestrially engendered, which often obliterate whole classes of once dominant organisms and provide opportunities for minor ones to come out of the wings.

Past instigators of mass extinction have included: asteroid impacts, widespread volcanic eruptions with concomitant ocean acidification, even the evolution of photosynthesis by cyanobacteria, which released the toxic gas oxygen into the atmosphere to the detriment of the once dominant anaerobes. Any and all of these scenarios will likely play out again somewhere in the fullness of Deep Time, but barring the elimination of all life on the planet, it is worth speculating on the impact such upheavals would have on the vegetated landscape.

For example, what would happen if flowering plants, also known as angiosperms, dramatically declined, perhaps taken out by some pandemic or selective evolutionary pressure? They’ve really only been common since the Cretaceous and it isn’t hard to imagine Kilpisjärvi’s abundant so-called ‘lower’ plants – mosses, club mosses and liverworts, moving into the vacuum and attaining gigantic proportions, as was the case during in the coal swamps of the Carboniferous Period.

Neo-Kilpisjärvi with giant club mosses A reduction in the availability of sunlight due to volcanic ash or widespread dust storms could have equally bizarre consequences. With green plants and algea in decline because of the challenge to photosynthesis, there would be a selective advantage for fungi, which might take over Kilpisjärvi forming bizarre, colossal structures as they did during the Devonian Period, some 400 million years ago, and again during the mayhem of the Permian mass extinction. Whether our own species would survive under such extreme and alien conditions is an open question, but life of some sort is almost certain to find a way. Perhaps fungi will regroup to form the planet’s supreme intelligence. Some would say, they already have!

It is this last point that gives me a vestige of hope. We Homo sapiens are a problematic creature, a classic, invasive species that thrives on disturbance, tends toward monoculture and displaces competing biota from its habitat. Yet in the overall scheme of things we are likely to be a transient phenomenon. We will either precipitate our own extinction, (and if the surviving ecosystems of the planet could sigh in relief, they surely would!), or we will find a way to live within our ecological means and develop a more equitable arrangement with the fellow denizens of the biosphere. My stay at the Kilpisjärvi Biological Station offered me the ideal vantage point to consider this conundrum. What we are in now is not so much of a ‘watershed’ moment but more of a ‘timeshed’ moment!

Neo-Kilpisjärvi with giant fungi

Vancouver Island highway scene At this ardently bright juncture of the year, there is something quite delightful about gazing up into the cool, rustling canopy of overhanging trees. It is a very deep memory for me. I must have been an infant, lying on the back bench seat of my parents’ old Buick, gazing up through the rear window at the dark tunnel of foliage billowing overhead, flashing here and there with orange bursts of interpenetrating sunlight. The dust from the road was starting to smell like the softer evening version of itself and the roadside insects, cicadas probably, hissed in their enormous, invisible numbers.

In my recent journeys between England and Canada, I have been struck by the contrast in attitudes toward what one might call ‘arboreal heritage’ between the two places. When driving on Vancouver Island I am inevitably torn between throwing up and crying whenever I see, as I almost always do, some of the last old growth Douglas firs (Pseudotsuga menziesii) getting hauled down the highway on some logging truck. Their rate of felling has been accelerated recently by a growth in demand from overseas, particularly Chinese, markets and the provincial government’s stupendously short-sighted decision to relax restrictions on the exporting of raw logs.

Each one of these ancient trees is a monument to the passing of centuries, a lynchpin around which complex ecological processes have evolved and yet we are losing the last primeval stands right at this very moment. To see one of those loaded trucks is like witnessing the carcass of a blue whale or a rhinoceros trucked off to a dog food factory but what more is there to be said? We have pointed our fingers yet the market economy has triumphed and the trees continue to fall. Soon all there will be left is a lingering sense of shame until that too eventually disappears. Outside a few relic specimens that happen to find themselves inside parks, the ancient fir groves of Vancouver Island will soon be obliterated. The Island Timberlands company continues to be a key player in this campaign of ecological extermination and is specifically targeting the large old trees on its vast private holdings to service an international market growing all the more lucrative as the global supply of first growth trees plummets.

this linden (lime) tree has been coppiced since at least the 13th century! While British Columbia has been embarrassingly and heartbreakingly remiss in its protection of Vancouver Island’s ancient firs, there are pockets of silvicultural enlightenment elsewhere in the world that can restore one’s faith in humanity. Last month Ruth and I spent a memorable afternoon at the Westonbirt Arboretum and got introduced to some of its innovative programs by director Simon Toomer. It may sound odd, but one of the highlights of our tour was seeing the manifold stumps of a recently harvested lime (Tilia sp.) tree, which has been harvested using the coppicing technique since at least the 13th century. The tree itself, which has spread out into about 60 individual stems, could be over a thousand years old! Coppicing (periodic cutting from regrowth regenerated from stumps or ‘stools’) is an ancient technique, suitable for a variety of mostly broadleaf trees, which paradoxically causes them to live much longer than if they were allowed to grow uncut. The practice periodically opens up parts of the forest canopy, allowing for an influx of light and a host of species dependent on brighter conditons, which enhances diversity in the forest, without massacring the entire structure over a large landscape as is done during industrial clear cutting. In British Columbia, it would definitely be worth testing out large-scale coppice management of Big-leafed maple (Acer macrophyllum) and Red Alder (Alnus rubra), both of which are capable of rapid regeneration from stumps and which have the potential to produce a range of sustainable wood products.

Westonbirt is also engaged in pioneering research on how forests will be affected by climate change and have initiated a series of long term trials of trees, hailing from a spectrum of locations, from the southern to northern parts of their present day ranges. If conditions continue to heat up, it is likely that trees evolving in more southerly latitudes will increasingly thrive within the British landscape, while more cold-adapted ones will only do well at higher latitudes and altitudes.

Back in British Columbia, I am beginning to draw similar conclusions. Though still in its early stages, the initial results of my Cortes Island ‘Neo-Eocene’ project indicate that some tree species now native to more southerly latitudes, such as Coast Redwood (Sequoia sempervirens) and Metasequoia (Metasequoia glyptostroboides) might actually grow faster under West Coast Canadian conditions than varieties currently prescribed for re-forestation, such as Western Red cedar (Thuja plicata). The difference is likely to intensify as northern climates continue to heat up. Climate warming is already causing massive mortality in northern populations of the native yellow cypress/cedar (Cupressus nootkatensis), because spring snow cover is no longer thick enough to protect their delicate roots from late frosts.

The premise of ‘Neo-Eocene’ is that we need to examine longer, more geologic time spans for guidance on how ecosystems might deal with the rapidly unfolding effects of anthropogenic climate change. During the Eocene Thermal Maximum, some 55 million years ago, taxa such as Sequoia, Metasequoia and Gingko, which are now extremely limited in natural distribution, did in fact range far into northern latitudes; so it makes sense to experimentally reintroduce them, especially to areas where the extant forest has been compromised by industrial logging or climate-change induced die-offs. Our concept of what is considered ‘native’ needs to be rethought, and we’ll have to expand our definition to encompass organisms that have been ‘prehistorically native.’ So bring on the Giant Ground Sloths! If only we could!

Apropos of the topic of ‘Deep Time,’ I have been invited to Finland this September to participate in the Field_Notes – Deep Time residency in subarctic Kilpisjärvi Finland. Along with the Smudge Studio folks and a bunch of other amazing people, I’ll be considering how developing a more ‘geologic’ perspective might help assess our trajectory into the deep future. As the world heats up again to levels seen only in the geologic, pre-human past, how will we cope? How long will it take for a subarctic place like Kilpisjärvi to feel like Lisbon or Lagos? Will more southerly latitudes, once temperate and agriculturally productive, become thermally uninhabitable? Will climate refugees, human and non-human, flood into the formally frigid northland? How might the northern biota adapt? Or can it? Anyway, I am endlessly excited.

Davidia tree in Wiltshire Another refugee from deep time is the wonderfully flamboyant Davidia tree, which dates back all the way to the Miocene, when it was much more widely distributed. Miraculously, a few groves somehow survived the intervening millennia deep within the gorges of Szechuan China. The tree with its magnificent, floppy white bracts, which some liken to handkerchiefs or doves, caught the attention of a French missionary, Abbé Armand David. He sent some dried samples back to Europe and a botanical sensation promptly ensued. It wasn’t long before a plant hunters from England and the United States were dispatched to what was then a very remote area, charged with collecting Davidia seeds for cultivation. In the Davidia’s case, this proved to be a boon for the global population as there are now fine specimens of the tree flourishing in parks and gardens throughout the temperate zones of the world, thanks to those early batches of seed. Davidia, as is the case with Metasequoia and Gingko are considered vulnerable in their native habitat, and it is only through their widespread cultivation outside the small territories in which they still naturally occur that their future remains assured. Yet who knows? These curious and obscure trees might contain within them a genetic willingness to reestablish themselves in vast swathes of the northern hemisphere, as the climate of the distant geologic past becomes the climate of the not so distant future. Here is a picture of the biggest Davidia I have ever seen. It was in full, glorious bloom, when I visited the the grounds of a lovely Wiltshire property, owned by the Guinness family. Judging by its size, this specimen seems likely to have been one of the first ones propagated – an ambassador of sorts from the distant geologic past that once again has a role to play in the beauty of the wider world.

a flurry of doves or handkerchiefs!

a green oasis Sometimes a bad idea just won’t go away. Though Vancouver’s future has been looking a lot greener lately, with the expansion of bike lanes and improved municipal composting, I was dismayed to learn that a city-proposed road expansion is threatening to wipe out Cottonwood Community Gardens, one of the Vancouver’s best-known examples of citizen-initiated urban greening. As a founder of Cottonwood, twenty-one years ago, I have fought this fight before.

Back in 1991, I started a campaign with a rag-tag group of East Vancouver residents to take over a three acre strip of city land on the southern perimeter of Strathcona Park, which had become a study in urban blight. The city had stopped enforcing anti-dumping bylaws in this industrial neighbourhood and mountains of jettisoned construction debris, landscaping waste, rotten furniture and junked cars were continuing to accumulate on the property with no end in sight, accompanied, unsurprisingly, by an increase in the rat population and the incidence of petty crime.

Tired of this officially sanctioned neglect, our little group of volunteers rolled up its collective sleeves, borrowed some wheelbarrows and shovels and got busy. With an enormous amount of hard work and a sense of community pride, we gradually transformed this unprepossessing piece of urban wasteland into an award-winning public garden and arboretum. It is without doubt one of the things in my life I am most proud of having done.

We called the place ‘Cottonwood Community Gardens’ as a nod to the giant cottonwood trees that tower over its northern edge, their rustling foliage a reminder of the area’s rich ecological past, when it was the marshy edge of False Creek, which once extended as far east as Clark Drive.

When word of our initiative got up to City Hall, we were informed that City Engineering had made plans to turn the dusty lot into a heavy equipment training area, despite being right beside a major park with heavily used playing fields, to which the dust churned up by the machinery would surely have drifted.

But those were the days of ‘recreational apartheid’ in East Vancouver, when the right-wing, Non-Partisan Alliance dominated city council and played favourites with the prosperous areas of the city that voted for them while turning their backs on neighbourhoods (like ours) that didn’t. The NPA dominated Parks Board was at that time busy assembling million dollar beachfront properties for parks in Point Grey and Kitsilano, while neighbourhoods on the East Side had to grovel to get broken teeter-totters replaced in their over-used inner-city playgrounds.

What we started out with

cleaning up

And if that wasn’t enough reason to continue with our intervention, a friendly Vancouver Sun reporter had tipped us off that City Engineering was quietly hatching a plan to build a major new truck route through the nearby Grandview Cut and run it right through this ignominious little property, funneling yet more smoke-belching transport trucks into our already polluted and congested environs.

Clearly City Hall was making some terrible decisions at the expense of the neighbourhood, so we needed to act fast. Whatever automatic legitimacy they may once have had was eroded by the pernicious neglect with which they treated the area, offering it up as a kind of sacrifice zone for their 1950’s vision of a vehicle-dominated city.

The ensuing work was very hard. We pulled out dumpster loads of every kind of disgusting trash imaginable – piles of moldy drywall, engine blocks, bloody syringes, used condoms – even a dead cat in a plastic bag – before we could do much actual gardening. And once we had dealt with all that insalubrious garbage, we hauled in wheelbarrow loads of rotten vegetables, gleaned from the produce warehouses on nearby Malkin Avenue, to make compost to enliven the impoverished soil. To water our initially meager crops, we had to haul buckets from the public washrooms in the park or wait for the rain to eventually fill them.

building the garden

composting with salvaged tofu

Yet we persisted, and despite some initial push-back from a few NPA councilors and some grumbling from City Engineering, we managed to prevail and marshaled the considerable public support we had been generating into a long-term lease. This gave us the security and the legitimacy we needed to get some small grants, with which we bought a few tools, installed an irrigation system, a greenhouse and a garden shed. The Environmental Youth Alliance joined our effort and soon started transforming the eastern flank of the property that had been covered in dense, trash-filled thickets, into what would become a thriving centre for youth-focused environmental education.

Gradually but steadily, the sun-baked and squalid expanse of dust and garbage we started out with gave way to groves of exotic trees and carefully tended allotments. The sounds of unfamiliar birds started to fill the morning air and there were cool pockets of shade with benches, where weary passers-by could sit and enjoy the slow resurgence of nature.

Two decades later, Cottonwood Gardens stands out from its surroundings as an oasis of biodiversity, a verdant interruption to an otherwise dreary vista of sterile playing fields and low-rise industrial buildings. A few years into our project, a pair red-tailed hawks built a nest in one of the large cottonwoods only to get evicted, a few seasons later, by a pair of bald eagles that still are there today, their sprawling twig nest and squeaking eaglets adding to the Edenic vibe of the place. I’ve often caught sight of visitors to the garden stopping and staring, incredulously, as these majestic raptors soar over the heat haze that simmers up from the factory roofs and then alight high on one of the cottonwoods to feed their young. It’s just not what you’d expect to see in what was long one of the city’s most deprived and green-space deficient districts, and yet even this is still relatively early in the long process of ecological recovery and one can only wonder what might eventually be possible – if, that is, we are allowed to continue with our long-running experiment in community ecological repair.

eagle’s nest

The seedlings and saplings we fussed over and watered all those years are now mature trees – a rich variety of them such as the blue-flowered Empress trees I grew from minuscule, milkweed pod-like seeds I picked up from under a gnarled, old specimen that still survives in Thornton Park. There are multiple kinds of mulberries, edible chestnuts, persimmons, Asian pears and groves of rare bamboo, along with extensive plantings of native species; all of them chosen for their ethno-botanical significance to the diverse heritage of the surrounding neighbourhoods.

In their well-tended garden plots, people from all walks of life coax forth a bounty of blooms, fruits and vegetables from what was once sterile rubble, sharing the food and recipes with their friends and neighbours in a living paradigm of what a green, inclusive city is supposed to be. This is an ‘open-source landscape’ that continuously evolves as a function of those who participate in it, with no real need for the top-down ministrations of bureaucrats, engineers and other members of the professional class. Cottonwood has always just run itself, a self-declared ‘autonomous zone,’ which is its true beauty but also makes it a threat to those who have a vested interest in maintaining the traditional power relationships that have controlled the evolution of the city.

Despite some headwinds at the start, Cottonwood has mostly had a cordial relations with civic politicians of all political stripes, and it didn’t take too long for even our foes to realize that the garden, which is essentially self-maintaining, creates environmental benefits and opportunities for community-building far beyond what is possible within the traditional parks system – at almost no cost. Cottonwood has been a very good deal for the city. With the rise of Vision Vancouver and their explicit advocacy of urban agriculture, I thought we were home free. During the last civic election, they even featured Cottonwood on their party web site as a prime example of a successful policy.

Imagine my shock then, when I found out last month that Cottonwood – despite all the accolades, the myriad hours of embodied volunteer energy and the many politicians who have schmoozed with us there, getting their pictures taken with babies and flowers – is once again on the chopping block, threatened by the same road, (though it’s now called a ‘super road’) we fought off all those many years ago. I was doubly surprised to learn that Vision Vancouver was behind the new spin on this same bad, old idea.

So how did we get into this ‘déja vu all over again’ situation?

Over the past year, Mayor Robertson and the rest of the Vision organization have been publicly promoting the removal of the Georgia and Dunsmuir Viaducts, a pair of concrete flyovers that are architectural relics of a proposed downtown freeway that got quashed by public outcry during the 1970’s. Though ridding the city of these monuments to twentieth century car culture might seem like a swell idea, (I got so excited about it, I even proposed to re-purpose them into a Highline style elevated garden), their removal will initiate a cascade of outcomes, not the least of which is that a substantial acreage of valuable real estate, now languishing as parking lots beneath the viaducts’ perpetual shadow, will get ‘day-lighted’ and hence available for development.

The viaducts, though not a freeway as such, do convey a substantial amount of traffic via Prior Street, a busy arterial that runs through the rapidly gentrifying Strathcona neighbourhood. Against the background of the viaducts’ proposed removal, the Strathcona Residents Association initiated a vociferous media campaign to get traffic calmed on Prior, to which the mayor responded with a proposal to build a so-called ‘super street’ that would divert much of Prior’s volume onto a newly widened Malkin Ave, whose right-of-way happens to pass right through the middle of Cottonwood Gardens. So we’re right back where we started from 21 years ago, only this time with a lot more to lose.

map showing road allowance

It has to be said though, the SRA has some valid arguments about the perils of Prior. It is a fast moving, high volume street with all the attendant traffic casualties, pollution and noise one might expect; hazards it shares with other high volume arterials in the area, where commuter and commercial traffic is routed through residential zones, as is the case with 1st Ave., 12th Ave., and a large section of Knight Street. To add to the complexity, the Province newspaper reported that traffic calming on Prior could add an average of $100,000 to the property values there, a not inconsequential outcome in a neighbourhood where real-estate prices have already skyrocketed.

Though this muddies the waters somewhat, it doesn’t negate the SRA’s safety concerns, but further underscores the need for Vision to step up with a much more innovative solution than the robbing Peter to pay Paul approach they have thus far hinted at, sacrificing Cottonwood, by now one of the city’s best-known ecological landmarks, for the uncertain outcome of traffic re-routing. Even without the Malkin ‘super street,’ the city itself anticipates the removal of the viaducts alone could actually contribute to a moderate decline in vehicles on Prior St.

as today (they) act as a magnet for commuter traffic with some commuters going ‘out of their way’ to access the viaducts via Prior St. With (their) removal, a significant proportion of commuters will naturally redistribute to other routes.

So the entire Prior issue may in fact be a red herring, with no real connection to what happens along Malkin except to add an unwarranted hysteria to the decision making process that plays nicely into the hands of the pro-development lobby.

a recent upgrade to enhance accessibility Along with the local concern about the viaduct removal and its effect on Prior, there is massive pressure being exerted by the federal and provincial governments, who are pushing a multi-billion dollar ‘Pacific Gateway’ program to expedite truck and rail traffic into and out of Vancouver’s port, with the aim of facilitating Canada’s growing trade with the Pacific Rim. The widening of Malkin has already been floated by City Engineering as a desirable way to meet these goals along with an overpass to ease the indignity of traffic jams at the at level crossing on Prior.

While Vision has not yet announced a decision on what they have already christened the ‘Malkin Connector,’ there is a creeping air of inevitability to their public communication on the subject. Mayor Robertson has made it clear he wants to expedite the matter and on a recent CBC ‘Early Edition’ interview, Vision councilor Geoff Meggs showed an alarmingly wishy-washy attitude toward Cottonwood and its future, telling his audience that Malkin has ‘always been seen as a future major arterial’ for ‘improving goods movement, (and that) ‘there will be impacts’ so that ‘the area can be set up properly (emphasis mine) to support jobs and development opportunities.’ These are the chosen words of an individual who has already made up his mind, though Meggs did add, rather noncommittally, the garden will be given ‘serious consideration,’ which is not, on its own, hugely encouraging.

In the end though, what we have here is not so much of a political issue, but a problem of urban design, which therefore should be solvable, if enough creativity and resources are directed at it. A ‘win-win’ outcome here would be a huge boost to Vision’s green credibility and give a clear signal they were serious about moving away from the traffic-centric, development driven, business-as-usual approach to running the city that has been so prevalent in the past.

Conversely, it would be wrong-headed in the extreme for Vision to sacrifice Cottonwood for the sake of a ‘super roadway,’ no matter how highly the engineering department recommended it. Given the by now iconic nature of this garden, I can pretty much guarantee there would be massive protest should it come down to the bulldozers moving in, and the spectre of photogenic young environmentalists and outraged senior citizens chaining themselves to the garden’s greenery to ward off city road-building crews would be death to Vision’s green brand and a gift to the right-wing forces so eager to unseat them.

So Vision had better come up with a solution that lives up to its party name – an imaginative solution that doesn’t pit neighbour against neighbour or trash this beloved oasis of urban nature – for the sake of vehicles. A world-class, ‘green’ city deserves world-class design that is both environmentally and socially at the cutting edge – a standard that may be beyond the tired, old orthodoxies the traffic engineers have had to offer. We can’t let Vision cut corners here, despite mounting pressures on them to do so from some very powerful players. But will they have the foresight and creativity to get this right? There is a lot riding on the outcome. Vision got a substantial mandate on their pledge to make Vancouver ‘the greenest city in the world.’ How they deal with Cottonwood will show us all how committed to their values they truly are. I for one will be watching very closely.

what we stand to lose If you’d like to weigh in on this issue and help prevent Vision from making a terrible mistake, here are some links:

‘Save Cottonwood’ Facebook group:

http://www.facebook.com/SaveCottonwoodCommunityGarden

‘Save Cottonwood’ Twitter feed:

https://twitter.com/SaveCottonwood

Geoff Meggs e-mail:

clrmeggs@vancouver.ca

Gregor Robertson e-mail:

gregor.robertson@vancouver.ca

Mayor and Council e-mail:

mayorandcouncil@vancouver.ca

(this isn’t the greatest way to get attention. It’s much more useful to e-mail individual councillors directly)

Here is a link to all the individual City Council contacts:

http://vancouver.ca/your-government/city-councillors.aspx

Also here is a link to my own history of Cottonwood:

http://www.oliverk.org/page/cottonwood-community-gardens

cherry blossoms at Brooklyn Botanical Gardens

Weeping cherries at Brooklyn Botanical Gardens

There are few things as lovely as the annual eruption of cherry blossoms – a time of year I very much look forward to on Canada’s West Coast. Vancouver is well known for its cherry-lined streets, which at this time of year can make moving through the city an almost psychedelic experience, with pink and white blossom clouds floating everywhere just overhead and petals drifting down to the rain-beaded pavement like kisses on tears.

Sakura zensen refers to the front of blooming cherry blossoms that creeps from south to north up the Japanese archipelago every spring. Blossom time is eagerly awaited all over the country and is marked by hanami celebrations, during which people eat and drink under the trees, whose short-lived flowers are revered as symbols of ephemeral existence. There is even a mathematical formula to predict blossoming time as a function of temperature and latitude, and the blooming is tracked with a precision that might elsewhere be accorded to dangerous weather systems.

For me, as for many others, the arrival of the cherry blossoms, no matter where I am, serves as a welcome harbinger of the season – a real sign the glumness of winter has been banished by the nascent radiance of spring. With this year’s unseasonably early warmth on North America’s east coast, the sakura zensen there seemed a little rushed. The Okame cherry sapling that had been planted a couple of years ago in front of Ruthie’s East 7th St. apartment was already sending out tendentious blooms by mid February, and by the time the end of March came around, the collection of weeping cherries at the Brooklyn Botanical Gardens was in full display. Laid out in the classical ‘hill and pond’ style, the BBG’s Japanese garden is one of the oldest of its kind in North America, having been established in 1914-1915 by the seminal Japanese landscape designer Takeo Shihota. By now, many of the trees are splendidly old and have a picturesqueness in their gnarled trunks and arching branches that contrasts beautifully with the delicacy of their pastel-hued, floral cascades that strew their petals onto the surface of the quiet pond, to be nuzzled by the whiskered snouts of carp.

In a kind of meditation on ephemerality, filmmaker Lucy Walker has released a most poignant movie she calls The Tsunami and the Cherry Blossom, which Ruth and I recently went to see at the Japan Society. Walker interleaves the joy of witnessing the cherry blossoms’ annual return with harrowing, first-person accounts by tsunami survivors who witnessed their friends and family get swept away to their deaths, and who must now manage somehow to get on with their lives. Though it is hard to see how anything good could come from such an epic disaster, Walker’s film gives us an insight into the Japanese sensibility of mono no aware; literally ‘the pathos of things,’ reminding us, even in the face of catastrophe, to love each other and to value each precious moment we are allotted, before it too drifts away like a petal on the wind.

Tompkins Square's American Elms

The hot breath of a globally-warmed, East Coast spring brings with it many surprises. A friend of mine, a young woman, writes to me from the surreal mid March heat of Montreal, the doors and windows of her apartment all open.

‘Is it you who once spoke of the new phenomenon of grieving natural landscapes? How about grieving a Season? Winter is a part of me. A genetic part I must say too!

Culturally, winter is at the center of so much life around here. So many memories about Winter. So long Winters. Skating on the river near my parents house when I was a kid… haven’t skated there since 1998…why? Because the ice hasn’t been thick enough to be safe to skate. Or there was just plain no ice at all. What about the ice fishing villages? What about hockey games outside? What about maple syrup…the sugar season has lost nearly a month in the past 10 years! This year it was a little more than 2 weeks. Spring won, Winter was too tired to fight back.’

Here in Manhattan, the leaves and flowers have been unfurling far, far ahead of schedule. The daffodils, usually in their prime by mid March have already come and gone in nearby Tompkins Square Park – a full month earlier than is usual. It didn’t take long for my sinuses to react to the the pollen billowing in from the park’s stately American Elm trees (Ulmus americana). These venerable giants, planted by the great Frederick Law Olmstead, still flourish in the city’s metropolitan parks long after their rural brethren have succumbed to the 20th century plague of Dutch Elm disease. On the island of Manhattan, the elms are protected by encircling rivers and a miles wide cordon sanitaire of buildings and pavement that prevents the elm bark beetle, which spreads the disease, from infecting them. It’s delightful to me that all those crushing tires and stomping feet are actually aiding conservation.

East Village spunk trees

As soon as the elm pollen fades, the cloying pong of Callery Pear (Pyrus calleryana) starts wafting through the East Village’s streets, the skeletal branches erupting into billowing, white flower clouds seemingly overnight, pushed into bloom by the strangely overheated breezes. Callery Pear is commonly known as the ‘spunk tree’ in these parts and the semen-like scent is strongest when the pollen starts going rancid after a bit of rain. The odor along St Mark’s place was particularly pungent this year, adding a whole other dimension to what some would say was an already rather skanky stretch of street. Once the trees stink themselves out, they become quite pleasant, bearing tiny Asian pears, from which my friend Marina Zurkow concocted a delicious alcoholic drink, after we foraged for the fruits on the shores of Brooklyn, last November.

A close second in the ejaculatory odor department is the Ghetto Palm, (Ailanthus altissima), which is found throughout the city’s waste places and terraines vagues. Thankfully it doesn’t flower till a fair bit later in the season!

How concerned should we be when the spring arrives so suddenly, so many weeks ahead of schedule? For someone like me, who hates extreme cold, this year’s eastern ‘non-winter’ should have seemed like a gift from the gods – a welcome break from the tedium of snow shoveling and galoshes. There have always been periods of aberrant weather – so why worry now?

The big picture on climate change is indeed concerning. Weather all over the planet has become increasingly extreme and records are being shattered left, right and center. The common denominator to all this chaos is global warming and it seems clear we are at the beginning of an epic shift. A recent study published in the New Scientist predicted an average 3 degrees C rise in global temperatures by 2050 – a scenario far worse than even the direst projections of a few years ago.

In addition to the ecological and economic effects, I wonder what will be the psychological outcomes of such aberrant weather? A certain predictability to the seasons seems necessary for our sense of well-being and if we can’t take some consistency for granted anymore, would it be any surprise if some of us go a little nuts?

Though we might be ‘grieving a season’ now, what will it be like when we forget completely what was once considered ‘normal’ and settle into a state of climate amnesia?

On a recent visit to suburban Toronto, I reminisced with my elderly parents over photos taken during my childhood. Forty years ago, we skated every winter on the ice of the nearby river. It was always thick enough to support the weight of snow clearing tractors and kiosks selling hot chocolate. Such reliably cold conditions seem almost inconceivable in that region now, a climate reality resigned to a distant past. An entire generation has grown up there since with no experience of the joys and tribulations of a reliably frigid winter. Perhaps the climate will someday settle into a newer, hotter ‘normal,’ but in the meantime it seems we’ll have to endure the instability of the current ‘abnormal,’ with plenty of unanticipated weirdness to come.

Vancouver Island style old growth forest liquidation

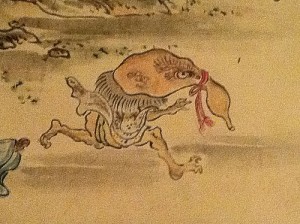

detail of a Japanese demon scroll from the Metropolitan Museum

I’m in New York again and have been here for a while. Right now, it’s about 3 pm, outside Washington Square Park, on the first day of 2012. A man wearing an expensive overcoat is projectile vomiting against a tree – a linden, I believe it is. An eager pug strains at its leash to lap up the mess, but the firm hand of his mistress snaps him back at the last instant.

New Year’s eve—the East Village was full of young women in spangly short skirts and tottery high heels, throwing up in the street and crying, while their boyfriends bellowed primal indignation at the indifferent, night air. Overhead, police helicopters rumbled and sirens caterwauled from all directions as Zuccotti Park, one of the city’s parsimoniously conceived ‘privately-owned public spaces’ got temporarily re-occupied by the anti-Wall Street protesters, before the riot-garbed might of New York’s finest wrested it back from the dangerous band of raw food enthusiasts and bicycle couriers (who posed such a clear and present threat to the security of this, the most powerful nation on earth), while each round of pepper spray and arm twist got live streamed into the ether by a hovering coterie of electro-pundits. All in all, it was a hell of an evening.

It’s been a long time since I’ve seen so much purging. It is said that Tibetan soothsayers and the Oracle of Delphi vomited after making their prognostications. The future made them sick, but then the past isn’t always so great either, and in 2011, the world seemed thoroughly to have gotten sick of itself. Though Occupy and the Arab Spring reminded us that entrenched, globalized systems of neo-Liberal economics and authoritarian government have (to quote Zizek) “lost their automatic legitimacy,” the outlook for the global environment has never, in the history of humanity, been so grim.

While some still pine for the evaporating American Dream, the opportunity to avert catastrophic climate change and forestall the extinction of countless fascinating species is slipping through our fingers like so many Styrofoam peanuts. Of course, at least subconsciously, we can all sense it, and to cope with the ubiquitous sensation of doom we sedate ourselves with apocalyptic pop culture, never more prevalent, as a casual perusal of Wikipedia’s listing on apocalyptically-themed video games will attest. These digital dystopias of burned out cities and smouldering, post-ecological terrains have infiltrated our optical-subconscious to the degree that we now feel increasingly at home in them, making the vestiges of the real, biological environment seem aberrant and atavistic.

You’re wondering now,

What to do,

Now you know,

This is the end.

Andy and Joey: Original Ska Version, 1964

Not to be outdone, I recently arranged my own ‘Apocalypse-athon’ watching Lars von Trier’s Melancholia and Jeff Nichols’ Take Shelter, more or less back-to-back, and I have to say the experience left me feeling strangely numb, as if someone had thoughtfully smeared Novocain on the insides of my wrists before handing me the X-acto knife to do myself in.

Let’s face it — contemplating the end of the world can give us a kind of frisson by stoking our anthropocentric egos, because after all, on some level, we would like to think the world will end with us. But that’s not likely to happen. There are plenty of tougher organisms out there who’d be happy to feed on our heaped, irradiated carcasses, while they watch us fade into geological history. Perhaps the rats and kudzu vines or whatever else moves in to take our place as the planet’s most visible organisms can work out a more sustainable contract with the planet than we did. One can only hope.

Barring all-out nuclear war or withering pandemic, our world, as we know it, will continue to diminish in increments —a forest here, a coral reef there, a watershed in some distant part of the world or maybe a bit closer to home.

A sad and perhaps typical small example of such ‘death by a thousand cuts,’ is taking place right now on Cortes Island— a mostly overlooked, densely forested blob of rock, off the inner coast of Vancouver Island, where I live part time. With its abundance of wild mushrooms, smurf-like New Age seniors and flaxen-haired hippie children, it can sometimes feel like living in the label of a Celestial Seasonings tea box, yet through good fortune and its reputation for a fierce culture of environmentalism, Cortes has been left with a few tracts of magnificent, old Coastal Douglas fir forest, a type of habitat largely extirpated from its former eastern Vancouver Island range. This enchanting ecosystem, where individual trees can tower to 200 feet, is the habitat of mountain lions, a unique maritime race of timber wolf, the endangered Queen Charlotte goshawk, rare bats, and an amazing diversity of fungi —some of them, such as the medicinally potent Agarikon, exclusively dependent on this age class and variety of tree.

Yet precisely because of their rarity, these large old trees are now valuable on the international timber market and have of late been under the acquisitive scrutiny of the corporate Eye of Sauron.

The Eye of Sauron In a twist of globalized connectivity, Brookfield Asset Management, the company behind the eviction of the Occupy Wall Street protestors from New York’s Zuccotti Park (which they own) recently bought up much of Cortes Island’s standing inventory of mature forest, which also contains most of island’s remaining old growth, particularly of Douglas fir.

Brookfield markets its Island Timberlands division to potential investors as:

One of the best sources of large Douglas fir, hemlock and cedar in North America for a broad customer base primarily located in Asia and North America…

Brookfield’s business model is perfectly clear: buy up the last commercially available pockets of ancient forest and liquidate them for maximum profit. This is eco-cide, pure and simple, but there may be little the good people of Cortes can do about it, save for physically blockading the logging equipment as it arrives in, to delay what perhaps is inevitable. In British Columbia’s privately owned forest lands, property rights trump all other environmental and social concerns, a status quo the forest industry lobbied hard to achieve, with substantial contributions to the governing Liberal party, who rewarded them by gutting regulation and oversight in a revised Private Managed Forest Land Act.

As outlined in their prospectus:

Brookfield focuses on investments in the region with a strongly embedded concept of private property rights generally supported by effective legal and land title systems.

By effective, they of course mean ‘industry friendly’ and the legal system in British Columbia is definitely that. Yet 2011 was the year people the world over stopped seeing the property rights of corporations as ‘self-evident’ and ‘automatically legitimate,’ when such rights override the well-being of communities and the environment. That is what the OWS movement was all about. What Cortes needs right now, is a massive ‘Forest Occupy’ response from those committed to maintaining the integrity of the vanishing ancient Coastal Douglas fir ecosystem in the face of a determined corporate assault. But will the islanders be able to muster the hundreds of occupiers it will take to pull this off? We’ll have to wait and see. Island Timberland plans to start its operations later this January.

What we will lose But what if Brookfield/IT prevails and logs off the venerable trees from its Cortes lands? To be sure, investors in its Timberlands private funds will get a little richer as the ships full of ancient logs ply their way across the Pacific and get fed into the maw of the Chinese construction industry. There is a painful symmetry in the fact that the profit squeezed from liquidating some of the last 1% of the original, ancient Douglas firs left on British Columbia’s coast will further line the pockets of society’s wealthiest 1%.

They probably won’t even notice. Environmentalists and bird-watchers will likely get a little more depressed as the sitings of Queen Charlotte goshawks and rare bats decline with the elimination of their prime breeding grounds, but even these people will start to focus on other things as the giant stumps sink slowly into the shrubby verdure of second growth. The timber company might even replant the ravaged land with industrially reared seedlings, each one secure under its own deer-resistant plastic cap. Gradually, what Jared Diamond calls ‘landscape amnesia’ will settle in and the degraded, industrially abused landscape will simply become ‘the new normal.’ And that to my mind is the greatest tragedy of all. We’ll lose something once basic to the human experience— the sense that a truly wild and ancient landscape can exist solely on its own terms, for everyone to appreciate, and not be sold out for the financial betterment of a wealthy few.

This is the way the world ends,

This is the way the world ends,

This is the way the world ends,

Not with a bang but a whimper…

T.S. Eliot – The Hollow Men

Scurrying demon

Euphorbia obesa

Haworthia truncata

I suppose you could say I am a patient man. I am fond of things that grow slowly like tortoises and ancient rainforest trees.

For the past couple of decades I have been absorbed in the hobby of growing various extremely slow growing plants from seed. These ones are from the driest parts of Southern Africa, an extreme environment in which they’ve evolved curious structural adaptations to survive during long periods of drought. Euphorbia obesa has done away with all manner of leaves or even spines and bides its time hunkering between the pebbles of its native Karoo region trying not to get noticed. Just in case, it protects itself with a toxic milky sap should anything want to give it an exploratory nibble. Once a year, toward the end of summer, a tiny cluster of flowers forms, male and female on different plants, and they await the visitation of some specially adapted insect to pollinate them. As these particular insects don’t inhabit the environs of my office, I hand pollinate the female flowers be means of a tiny sable paint brush which I carefully dust with pollen from the male one. Timing is everything and I have to be lucky enough to have a male and a female flowering simultaneously in my little collection. The result, over the past fifteen years, has been a number of bulbous progeny, and I feel proud to be propagating this strange little plant that is critically endangered in the wild and doing it right here on my Canadian windowsill.

Hailing from the same general area is the Haworthia truncata, whose contractile roots pull it down into its gravel habitat when things get a bit too hot. In order to absorb enough light for photosynthesis in its partially subterranean situation,H. truncata has evolved translucent windows at the end of its truncated leaves, which funnel light deep down into the plant.