|

|

North Troy NY brownfield savanna

safari into the Williamette Cove brownfields

Those of who call ourselves ‘environmentalists’ have a tendency to imagine a prelapsarian wilderness that once was pristine and then became progressively defiled and diminished through the carelessness of humankind. But the earth had been through many environmental catastrophes long before we came along– though this doesn’t exactly excuse us from our manifold sins. The infamous Chixculub asteroid impact suddenly ended the long reign of the dinosaurs and the more insidious yet equally catastrophic evolution of photosynthesis deep within the cells of certain cyanobacteria contaminated the earth’s early biosphere with oxygen– a fatal poison to the majority of organisms present at the time, resulting in what is now known as the oxygen catastrophe, a mass die-off of the earth’s biodiversity and a climate change event that froze the planet in the longest snowball earth episode in geologic history.

What is unique in the present (Anthropocenic) moment is that we know we are causing a massive and likely suicidal ecological crisis and yet choose not to do anything about it. Here we are at the tail end of 2014 with atmospheric CO2 levels higher than they’ve been for 800,000 years and the 6th mass extinction accelerating to the point where the earth has lost half of its wildlife species in the past 40 years. Political leaders, particularly those of oil rich countries like my native Canada either willfully ignore the scientific consensus or in the most egregious cases, (again Canada), actively censor the findings of scientists and even weather forecasters. Because a little knowledge can be a dangerous thing. Or is it?

In a recent video, Žižek makes the perhaps startling case that there is considerable poetry in our present situation, that is to say, our disavowal, our state of knowing that something is true and yet acting as if it wasn’t. He argues that to “truly love the world, we must love its imperfections,” including, presumably, the ones for which we are directly responsible. “In trash,” he declares “is the true love of the world,” a sentiment similarly observed by a Zen priest in the masterful little documentary, Tokyo Waka, which explores the world of Tokyo’s ubiquitous and trash loving crows. To be more precise the priest observes: “In trash is the residue of desire,” a sentiment perhaps less direct but still elevating garbage to a kind of reified affection.

To follow that logic, when an entire landscape becomes trashed, it should be particularly worthy of our love and it was in this spirit that I embarked upon my summer explorations…

But first some background: The Superfund was originally set up in the America in 1980 to identify and facilitate the cleaning up of the country’s most hazardous waste sites. In theory this might have created sufficient funding and legislative willpower to deal with this dangerous and unhealthy problem but between partisan politics and bureaucratic ineptitude, implementation fell far short of what was needed.

Though most people would want steer clear of toxic wastelands, I wanted to see if there were any adaptive ecological processes operating there that might be transforming these zones of exclusion into useable habitats. I had the strong sense that conventional ecologists and environmentalists might be missing something very important, that nature was capable of doing an end run around our destruction, if only we would get out of the way. My summer safari took me to sites on both sides of the continent–Troy, NY and Portland, Oregon–and what I observed there gave me some hope and insight into nature’s surprising ability to colonize the messes we have left behind.

I was invited to Troy by my pal Kathy High for a collaborative investigation into the area’s extensive brownfields. Once known as the ‘collar city’ for its shirt, collar and textile production, Troy is considered the birthplace (and graveyard?) of the American industrial revolution. A fortuitous confluence of rivers made it possible for early factories to harness abundant mechanical (and eventually hydroelectric) power as well as to cheaply transport products and raw materials. Like so much of America’s industrial heartland, the area has suffered from economic decline and many of its once thrumming factories lie in ruin in within highly contaminated terrain.

Some of the worst sites are situated along the banks of the picturesque Hudson River, which transitions here from tidal to freshwater, the end of a long estuary. Downstream, all of the Hudson is classed as a Superfund site because of extensive contamination by PCBs, a potent carcinogen, dumped for decades by the General Electric Corporation as a byproduct of manufacturing transformers and other electrical components. PCB’s are a persistent organic pollutant (POP) that bioaccumulate in the river’s fish, making many species unsafe to eat–including the reputedly delicious striped bass that spawns nearby at the junction of the Hudson and Mohawk rivers.

chimney swifts over North Troy Despite being a very degraded ecosystem Troy’s former industrial landsa are full of surprises. As part of a summer youth program, I led a ‘bio blitz’ of a community garden that had been established on a brownfield site near the Sanctuary for Independent Media. It wasn’t long before we found a magnificent stag beetle hiding in the rotting stump of an (invasive! exotic!) Ailanthus tree. High overhead, chimney swifts traced their invisible arabesques into the topaz air of the summer evening. This species, has long adapted to human presence and as indicated by its common name, makes its nests in disused chimneys. The chimney swift is a close relative of the Vaux’s swift, which puts up a spectacular display every evening as great clouds of the birds funnel into in a large chimney at the Chapman School in Portland, Oregon.

A local Troy resident told me she had recently found red-backed salamanders under debris in her backyard yard, situated quite near some of city’s most contaminated industrial sites, with nothing that might be deemed ‘intact’ woodland anywhere in the vicinity. With the sharp decline of amphibians worldwide, even in protected national parks, it might seem surprising to find them surviving in such anthropogenically disturbed habitats but this is consistent with findings in the UK where rare newts and other amphibians as well as lizards, slow-worms and grass snakes make their last stands in these unprepossessing environs, among the trash, eroding pavements and ruined buildings. In fact brownfields turn out to be far more suitable habitat for these delicate little creatures than is the intensively managed agricultural landscape that has obliterated large tracts of Europes’s biologically diverse ‘Kulturlandschaft’.

stag beetle in Ailanthus stump At a Superfund site at the foot of Troy’s Ingalls Ave, I watched turkey vultures soar over an edenic looking mosaic of meadowy expanses that have cloaked the heavily contaminated soil. These neo-savannahs are punctuated by lush groves–a botanical mosh pit of weedy natives like box elder, black locust and cottonwood mixed in with exotic Ailanthus and Paulownia. All of this is gloriously unmanaged, left to its own rampancy, and though the species constituting this habitat are largely considered ‘invasive,’ they embody a new kind of ecological becoming, their novel juxtapositionings and processes of succession–a ‘Nature 2.0′ in the making.

If we put aside our purist bias, we might celebrate brownfields as territories of regeneration and marvel at how they adapt to the disturbances and wastes we leave in our wake. One might even regard them as ‘wilderness’ of a certain kind as they are one of the few ecological realms we have let slip from our control–leaving them free to reconfigure themselves and follow independent trajectories of neo-evolution.

Troy NY’s future brownfield rangers The collapse of industry though, leaves more than just picturesque ruins and novel habitat in its wake. For human communities,‘Detroitization’ means decaying infrastructure, diminished economic opportunity and the adverse health effects of pervasive chemical contamination. If sufficiently de-toxified, these lands can be rehabilitated as perfectly reasonable urban nature parks (see my previous posting on Berlin’s Templehof airport) but the challenge is to do so without diminishing their often surprising biodiversity.

Troy might be an ideal location for a Brownfields National Park, where local youth could work as ‘brownfield rangers,’ leading tours of the area’s ecological and historical heritage as well as doing field studies and cataloging the species to be found there. Though this necessitates a change of perspective in what we North Americans typically think of as a ‘natural’ park experience, it is high time we open our minds to such opportunities. Brownfields are the future. Brownfields are us!

Over on the other side of the continent, I met up with artist Marina Zurkow in Portland, Oregon. Together, we led artistic incursions into a Superfund site on the edge of the Williamette River. We explored first by water, using a flotilla of kayaks peopled by an intrepid collection of individuals who responded to our call for participation in what (to the less adventurous) might have seemed an arcane enterprise. We conceived our expedition as a kind of group imagination exercise and christened it -“IF YOU SEE IT–BE IT!” in the spirit of the biosemiotician Jacob Von Uexküll, who did such groundbreaking research on the spatio-temporal worlds of animals, which he termed the ‘Umwelt.’ Aboard our tiny craft, we collectively tried to imagine/channel what it might have been like to navigate the contaminated and disturbed riparian environment from an animal’s point of view (water striders, otters, sturgeons, etc.) – inhabiting (in our mind’s eye) their biosemiotic state, ‘becoming’ them, as it were, in a collective thought exercise.

Marina’s long term plan is to construct a raft-like roving laboratory she calls the Floating Studio for Dark Ecology, on which artists and researchers ply the river, exploring its narratives of contamination and recovery as well as disseminating practices of contemplation and engagement between its human and non-human communities.

Our early evening voyage proved suitably anthropocenic: a bald eagle gliding through the shimmering cottonwoods of Ross Island–a section of river whose bed is being continually scoured by heavy gravel mining machinery–the blue tarp and scrap lumber bricolage of homeless encampments festooning the banks of the Williamette–the third world within the first world, the metabolic waste of neoliberal capitalism as it eats its way through our material reality.

Neo-ecologies of Williamette Cove Once again there were fascinating and new ecological assemblage in these zones of dereliction and abandonment. Washed up on the industrial shore of a former shipyard–exquisite hydrozoans of a type I have never seen before:

hydrozoan The brownfields of the former factory site at Williamette Cove, though dangerously contaminated with heavy metals, wood preservatives and organic pollutants, proved not so ‘brown’ after all and were resplendent with novel botanical groupings–neo-succession! Native species like Arbutus menziesii (Madrone) formed habitat groupings with such hardy exotics as Paulownia tomentosa (princess or empress Tree) and Crataegus monogyna (European hawthorn). It is thought the empress trees made their original landfall in North America via their fluffy seeds, once used as a packing material for porcelain and other fragile goods originating in China and Japan. A gust of wind and an open crate at the dockside and their botanical colonization of the continent would have been begun.

In addition to brownfield neo-ecologies there is a parallel and equally fascinating neo-geology emerging from the material detritus of our age. Mineralogically, these are mostly composites and conglomerates or pyrolized residues of industrial processes such as coke and slag, as well as ceramics that have been fired into the form of brick, tile and pipe, much of it broken up into rubble. This so-called ‘urbanite’ is dominated by concrete and ferro-cement in various states of decay and petrochemically based asphalt and asphalt concrete, widely used in paving.

Sometimes though, a geologic object occurs that is of more obscure though still clearly anthropogenic provenance. At Williamette Cove, we came upon an exquisite specimen–a fossil of sorts–consisting of a fused mass of ribbed metal fragments, the armouring of industrial electrical cable, set within a matrix of a more indeterminate material, which might have been partially incinerated plastic. Perhaps this mystery mineral was formed when some itinerant metal collector tried to salvage copper wire by throwing scrounged cable into a campfire to melt off its rubber insulation and loosen the metal cladding. I may never discover this exquisite object’s true origin and it might well become the topic of frenzied conjecture to some future archeologist, wondering what our experience was like as we drifted deeper into the fraught and turbulent horizon of our anthropocenic future.

neo-geological form

zone of alienation

zone of regeneration

In Tarkovsky’s 1979 film Stalker, a mysterious guide leads a couple of characters known only as ‘the writer’ and the ‘professor’ into a post industrial ‘zone of alienation’ where it is promised one’s innermost wishes can be granted and where the rules of physics no longer apply. The ‘Zone’ is completely abject, a place of weeds, broken machinery and the ruins of factories and yet it is hauntingly beautiful in a way that is triggered (perhaps) by our deep yet unconscious familiarity with such landscapes –the places Walter Benjamin called the optical subconscious, the quotidian zones in which we are so fully at home we don’t even realize we live there.

These aren’t the iconic, aspirational landscapes of snow-capped mountains, palm fringed coral beaches and glittering urban skylines –the stuff of screen savers and photo murals in tacky restaurants, but rather the prosaic localities we continuously experience, perceiving them peripherally, from the corners of our eyes yet rarely explicitly acknowledging. The French term ‘terrain vague’ comes closest to the way these places feel and they might take the form of a trash-strewn railway embankment or an abandoned car park with rank vegetation coming up through the broken pavement or perhaps one of those forlorn, zones of contamination we refer to as brownfields, which have become the global hallmark of industrial decline.

I think back on my Amtrak journeys through the rust belt of America, marvelling at the Piranesian grandeur of once opulent railway stations left to crumble at the trackside, the ruined vaults now sheltering only birds which dart in and out of the shattered arrays of windows. The train keeps chugging lethargically (it is Amtrak after all, itself a symbol of decline in American technological ambition) through dour, neglected expanses, prosaic, ugly, endless –you can’t really call it ‘countryside’ exactly– but for the occasional scruffy woodlot and oily wetland which passes between the wrecking yards, quonset huts and derelict factories. This is (as Deleuze might call it) a ‘striated’ landscape that interleaves the decaying residue of a once prosperous age of material production with a resurgent, weedy nature –an ecology of discard, a ‘zone of alienation’ where anything might appear– a muddy field strewn with bone white shards of dishes and upturned toilet bowls, the twisted wreckage of a carnival rides left over from, what? A tornado? Perhaps, even–though I did not experience it–the fulfillment of one’s deepest wishes…

But is this not the state of the world as we all now know it? It’s the Anthropocene, baby, and collectively we’ve chewed up every inch of biosphere; extirpating, contaminating and cultivating ourselves into this, the global ‘Nature 2.0’ reality, where even the unfolding of weather and the chemistry of the oceans have become extensions, artifacts of human existence. So past the point of no return are we that we might as well discard nostalgic notions of ‘wilderness’ and adopt a new, Anthropocenic grammar, already envisioned by the likes of Žižek and Morton, which more aptly describes the hybridized, pervasively humanized environment in which we now live.

terrain vague Our planet has essentially become one, big ruderal ecology (from the Latin ‘rudus’ meaning rubble), characterized by the large-scale extinction of species–passenger pigeons, big cats, rhinos–as well as entire ecosystems–Madagascar, the Arctic, coral reefs. And yet there is a curious, parallel process of adaptive evolution occurring in the disturbance ecologies and debris fields (called anthromes) we leave in our wake.

At Chernobyl (one of the greatest ecological and social messes we have ever been responsible for, a byword for lethal, irreparable contamination and epic technological failure) some bird species–and by no means all of them, as many kinds there have significantly declined–but certain bird species seem to be surviving by evolving a tendency to produce more cancer-fighting antioxidants which help resist the effects of the pervasive radiation. Scientists are calling this “unnatural selection” and it is already driving evolutionary change.

canid hyperorganism In much of eastern North America, the wolf was largely wiped out during European colonization but it has recently come back not as a wolf exactly, but a kind of hyperorganism–a three way hybrid between wolf, dog and coyote that pushes the boundaries of what it even means to be a species. With the precipitous decline of the ancestral wolf, an ‘eye of the needle’ effect ensued in which wolf genetics became more ‘soluble,’ more open to other singularities and contagions, a necessary precondition for the evolution of a new, protean canid, able to prosper in the niche now available for some canny predator able to exploit the pervasively humanized and ecologically degraded environment of second growth forest and exurban sprawl–the kind of places that are an anathema to the so-called ‘pure’ wolves of the primeval wilderness but which offer abundant prey resources of lawn-fed deer and genetically moronic pets. Enter the ‘Coywolf’ or Eastern coyote. They might be a product of ‘unnatural’ selection, but they sure are hungry!

Such novel recombining is occurring at a multi-species level too, with entirely new hyperecologies evolving as weedy, native species commingle with invasive exotics, all of them jostling and repositioning themselves into configurations that never would have existed ‘naturally’ but which now comprises recognizable and widespread landscapes of brownfield savannah and emergent, wasteland forest that are found throughout the world in pretty much any place we have exploited and then turned our back on. Many of these organisms are the hardy cosmopolitan nomads we are all used to seeing, such as tree of heaven (also known as the ’garbage palm’), black locust, pigeons and rats, but perhaps surprisingly these unprepossessing assemblages can support a diverse array of other species, some exceedingly rare, which hail from habitats like gravelly steam banks and dry heaths now largely obliterated from a hinterland dominated by chemical intensive farming and vast, ecologically sterile acreages of housing developments and big box stores.

In the UK, where humanized landscapes are particularly well studied, it is estimated that up to 15% of the nationally rare insects and spiders are dependent on brownfields for their survival as do several species of reptiles, orchids and other rare plants.

I was delighted last March to visit the grounds of the now disused Templehof Airport in Berlin, which as a result of citizen pressure has been set aside as a kind of publicly accessible ruderal ecology park. Here one is greeted by the incongruous site of windsurfers careening along miles of abandoned runways while skylarks hover high over vast swathes of tawny grassland, singing and establishing territory in their annual rite of spring.

Along with a surprising diversity of meadow dependent birds – wheatears, shrikes, whinchats and so on, 236 bee and wasp species have been recorded on the grounds, more than 40 of them endangered or near extinction, particularly those dependent on the open, sandy microhabitats that have all but vanished in the over-managed environs of the countryside.

gestapo prison excavations

airfield meadows

This wonderful interleaving, this striation, this ‘to-ing and fro-ing’, between architectural ruin and ecological renewal is to my mind a tremendously optimistic model for the future of parks in general and for our appreciation of landscape as a whole and it is in promoting this aesthetic that Berlin is very much at the fore. The Templehof park doesn’t try to paper over its problematic Nazi past but lets us grapple with it by preserving the forbidding Fascist architecture and letting us watch archeological excavations of Gestapo prisons and slave labour camps taking place on on its grounds.

At the same time we are offered profound hope by witnessing innate processes of ecological and cultural regeneration get encouraged, not in an over-planned or commercialized way, but from the ground up, in a way that is distinct from the banal, generic late capitalist aesthetic that so frequently defines urban renewal initiatives elsewhere. By being leaving it alone, Templehof is able to renew itself.

Though the global ecological crisis is deep and inestimably tragic, we can perhaps allow ourselves to cautious celebrate the evolution of a new kind of nature, a ruderal nature, where kestrels soar across the heat haze of abandoned runways that are slowly becoming encrusted with lichens and grasses and where rare wild flowers can find a toehold among the rubble of some of history’s worst crimes against humanity. The sky is filled with the coloured sails of paragliders and a bumblebee is making its first foray into the vast warm vault of another spring.

sailing the runways

skylarks nest here

where it all went down… The great blue bowl of the California sky has doubtlessly presided over some strange affairs, but perhaps none is stranger than the serial cycle of entrapment and petrification that started around 38,000 years ago in a collection of deceptively limpid ponds in what is now a quiet park in downtown Los Angeles. After it rains here, the play of sunlight and clouds is mirrored on their lambent surfaces, beneath which lies a menacing secret: for what first might appear to be a refreshing pool in an arid terrain is only a thin film of water obscuring an abyss of sticky bitumen, which has been oozing steadily from petroleum-bearing rock formations deep beneath the earth.

These are the notorious La Brea Tar Pits and since the days of the Pleistocene their peculiar configuration has served as both death trap and mausoleum for thousands of creatures–great and small, thirsty and merely curious–who venture into them and get stuck in their viscous pitch. Like a giant version of the ‘cockroach motel,’ once they ‘check in’ they never ‘check out’ and indeed the thrashing and bellowing of trapped victims attracts predators, whose natural wariness proves no match for the promise of an easy meal, ensuring they too are quickly doomed after jumping in for the kill. And so for thousands of years, whole conglomerations, entire food chains of animals have met their ends here: predators and prey sinking down alongside each other, each creature naïvely repeating the fatal mistakes of its predecessor: sabre-toothed cats and Dire wolves, with fangs and claws sunk into the contorted bodies of mastodons and camels, all of them frozen in elemental struggle as if in some Classical frieze. Not even the carrion eaters escaped the gruesome fate. Outsized vultures, giant condors and hideous, meat-eating storks, wheeling and squabbling for landing rights on the bloated corpses and almost corpses, snagged themselves when a carelessly extended talon or trailing pinion made contact with the merciless tar, that pulled them in, flapping and screeching , never to fly again. As well as being deadly, the tar has miraculous powers of preservation. The seething, interconnected beds of bone that have accumulated there have kept scientists busy ever since they first started excavating back in the early 1900s. Many of the rich paleontological finds are on display at the adjacent George C. Page Museum.

When I was a boy in Toronto back in the early 1960s, a small piece of the La Brea Tar Pits was on display in a dusty diorama at the city’s Royal Ontario Museum. This was a few years before the ROM adopted the loathsome trend for ’interactivity’, which consigned much of the museum’s extensive palaeontology collection to back rooms, out of public view, and what we got instead was an ersatz mishmash of mood lighting, audio tape loops and fibreglass models of dinosaurs standing aura-less amid plastic palm trees. Anyway before all that stupidity, I remember how transfixed I was ‘just looking’ at the thing itself, without being told how to think about what was in front of me – the tea coloured skeleton of a sabre-toothed cat, its outsized canines filigreed with tiny age cracks, poised to stab the neck of a hapless ungulate (a proto-camel? an extinct horse?) which had already begun to sink. It was the futility of it I remember the most, that both animals died together in the same inescapable way, the first doomed by thirst (or bovine idiocy), the second by carnivorous savagery. And I knew this scenario was to play itself out again and again because it was elementally and inherently unavoidable. Presiding over the sad scene was a tromp-l’oeil painted backdrop of a clot of vultures, hanging like wind-ripped umbrellas in the branches of a skeletal tree, and in broad brush strokes, a distant herd of mammoths melting into the horizon.

When I finally, this spring, got to tour the La Brea tar pits firsthand, I couldn’t help but see them as a kind of trope for contemporary times.

LA is a strange enough place to begin with–its palm-studded freeways and rivers of twinkling windshields pouring into the heat haze of the hyper- illuminated horizon–a place at once banal and startling, the High Baroque of American drive-thru suburbia amid scintillating beaches flooded in a golden, Canaletto-esque light. There are people there, of a certain age, whose faces have been so surgically altered it is as if they’ve been sucked through a magic wind tunnel. The mismatch between their wrinkle-less heads and the sun-withered bodies is chimerical, as if bands of Surrealist ‘exquisite corpses’ had gone AWOL, pulling themselves off the canvases and walking around. Los Angeles is the very essence of the American Anthropocene and yet prehistory bubbles and belches everywhere just beneath the surface. The city sits astride a massive oil field, where serried ranks of mini malls and tract homes lie nestled in the napes of brown hills and rustling eucalyptus groves, the edges of which bleed into a kind of terrain vague of ponderously nodding pump jacks tirelessly sucking petroleum out of a deposit dating back to the Miocene– a geologic epoch already long gone by the time the first mammoths sank into the tar.

Wandering through the pleasant grounds of Hancock Park, the past becomes the present and one soon encounters a pair of giant, chocolate-coloured ground sloths, like outsized Easter confections, placid and dim-witted in expression, yet armed with menacing fore claws that could easily rip the face off almost any attacker. As late as 10,000 years ago, these ungainly beasts lumbered across what was a vast North American range – their remains having been found from the Yukon to Mexico. At La Brea, they were regular victims to the suffocating tar.

yours truly and the ground sloths

In a still bubbling tar pit encircled by construction fencing, a family replica of gigantic Columbian mammoths replays a pathetic tableau. An adult is hopelessly stuck in the pit, its mouth agape in panic, its trunk frozen between the great curved brackets of its tusks, frantically gesturing to its mate and calf who stand helplessly on shore. The theme of serial entrapment and the futility of instinct gets amplified as soon as one enters the museum, which is packed with reconstructed skeletons and glass cases full of phylogenetically arranged remains, memorializing the legions of hapless creatures who died there over thousands of years, who just couldn’t stop themselves from making the same fatal mistakes over and over, in a senseless and recurring cruelty against which no benevolent god or Walt Disney narrator would intervene to warn ‘Stay out of those pits, yo!’ If only Spielberg had been in charge…

In paleontological terms, the tar pits are what is known as an ‘evolutionary trap.’ These create a stimulus that certain species are unable to resist and the results are often fatal. A contemporary equivalent has been the sad epidemic of dying albatrosses we’ve been seeing on Pacific Islands, their body cavities packed with bits of plastic that they seem programmed to snatch up from the waves and swallow in place of their natural food. Like the victims of La Brea, they just can’t help themselves.

Back at the Tar Pits, the Dire wolf (Canis dirus) seems to have been a particularly slow learner. To date the remains of over four thousand of them have been found there with doubtless many more to come. One of the more impressive displays at the George C. Page is a long, back-lit display, like something out of a high-end shoe store, containing hundreds of Dire wolf skulls, each an embodiment of one individual’s lack of impulse control. It seems that whenever a pack of them came upon an animal in distress in the tar, they would pile right on in on top of it, dooming themselves by their own overly developed killer instincts and susceptibility to peer pressure. The fact that the Dire wolf seems to have been exceptionally competitive, didn’t help matters. Males in areas where there was high population density developed outsized fangs with which to fight each other. It’s hard not to imagine the pack dynamic being a rather savage affair, especially when they chanced upon a bleating animal, trapped in tar. For the Dire wolf, there likely wasn’t a lot of time for second guesses. Though heavier and likely much meaner than their little cousin the coyote (Canis latrans), the Dire wolf failed to survive the Pleistocene, while the coyote still thrives in LA’s hills and canyons, feeding on what it finds in trash cans and snatching up unguarded pets. Though the Tar Pits weren’t the only factor in the Dire wolf’s continent-wide extinction, the evidence of its behaviour at La Brea indicates an inherent inflexibility, which must have been a major handicap in what, at the end of the Pleistocene, was a rapidly shifting set of conditions including changes in climate and the incursion of the first Paleo-Indians into its environment, who competed aggressively with the wolf for prey.

dire wolf skulls Though we may think our species’ ability to show foresight gives us particular resiliency–after all we started out in minuscule numbers, survived an Ice Age and proceeded to take over the world–we find ourselves now under a similar delusion to that which befell those hapless beasts at La Brea. Could it be that in the black, viscous materiality of petroleum we have finally met our match? Though we may think we have mastery over our fate, we seem blind to the possibility that it might be a substance that has control over us…

As an evolutionary trap– a nemesis–petroleum is the perfect agent. It is the very essence of death, a distillate of corpses from untold myriads of prehistoric organisms, which has quietly waited for us beneath the earth. If substances possess their own agency, as Jane Bennett surmises in her (2010) Vibrant Matter, is it so far-fetched to suggest that petroleum is luring us in, manipulating our innate behavioural vulnerabilities to ultimately absorb us into its oozing corpus? Like the sabre-toothed cat and Dire wolf before us, petroleum has exerted its ability to hypnotize, to communicate directly with our vulnerable animality, bypassing our much vaunted capacity for reason and discernment. It’s not that big a leap from the Tar Pits to the Tar Sands…

As happened to the Pleistocene creatures who got stuck in it when they put aside their caution, petroleum–ever protean– has set its exquisite trap for us in the form of a fata morgana, which gives us the illusion of eternally abundant and convenient energy with no long-term consequences. We are probably already in too deep to realize what has happened; that we are becoming petroleum, absorbed by the wily substance to become one with its subterranean deposits.

The Anthropocene might be remembered as a geologically brief period during which our species was allowed an overdraft, a blip during which we extracted a quantity of the black ooze before we had to repay our loan with the highest of interest; our lives, and those of the countless other organisms we took with us after we have made the planet uninhabitable. In so doing, we are offering up billions of putrefying corpses, untold tonnage of petrochemical garbage and entire landscapes of withered vegetation to be re-incorporated into the geologic, where unstoppable tectonic regimes will reprocess it into the mother of all oil fields.

So it is a mistake perhaps to wax too moralistic about our failure to rein in our natural impulsivity, to plan sensibly or imagine a future free from our addiction to this substance. Our connection to it might be too deep, too genetically encoded for us to resist through mere self critique.

Following the logic of the Dire wolf, our own species is competing increasingly viciously for what is (for the geologic moment anyway) a limited resource. The power elites in localities dependent primarily on petroleum production (Russia, Nigeria, Libya and others) have drawn whole societies into animality and impulsivity.

Even Canada, long a role model for liberal democracy, has slid into this petro-brutality. Under the prime ministership of oil-mad Stephen Harper, its government has declared a totalitarian war on scientists who study climate change and associated environmental contamination. The uncomfortable facts they keep bringing up highlight Canada’s abysmal record on these matters, which, aside from being an international embarrassment, threaten to push the usually complacent Canadians into a confrontation with the ecological Real (boring!, depressing!), invoking questions the Harper government is determined not to let us ask. Important and long-standing research facilities and environmental monitoring stations have already been shuttered, their scientists sacked and the scholarly material packed away or even thrown into the garbage. Those few scientists still working have been given STASI style minders, through which all communication with the public must be vetted. They even shadow the scientists at academic conferences to make sure they don’t say anything deemed ‘off message’ to the government’s single-minded agenda.

Yet given that our attraction to petroleum is demonstrably biological, can we really blame the individual oil worker, warlord or myopic Canadian bureaucrat? By doing their part to hasten mass extinction, they are in the service of the long term interest of petroleum itself. By extending its sticky tendrils through a higher dimensional space than most of us are letting ourselves imagine, petroleum assumes the characteristics of what the philosopher Timothy Morton calls a ‘hyperobject,’ an entire set of relationships, interactions agencies and desires of which we are but a small and transient part.

tar sands (via National Geographic)

dwarf birches and tundra  suddenly – reindeer!

The morning broke grey and brooding outside the Kilpisjärvi Biological Station and after a quick breakfast, we were on the trail, hiking up Saana Fjell, guided by Erich Berger of the Finnish Bioart Society. The idea was to familiarize ourselves with the geology, ecology and cultural history of the vicinity so we could dive into our research plans as soon as possible.

The Australian bio-hacker, Oron Catts had already been here for a week to do some scouting for his group’s ‘Journey to the Post-Anthropogenic’ project. They planned to perform a comprehensive bio-archeological survey of the crash site of a German Junkers 88 bomber that came down on Saana in 1942, which included a metagenomic analysis of the plane’s debris field and a recreation of the crash trajectory using a remote-controlled drone.

debris field It wasn’t long before we passed the tree line where the mountain birches gave way to an expanse of open tundra sweeping out before us in a swath of russet heath and exposed rock, with quivering patches of silver cloud here and there snagged on the crenellations of the topography. As if on cue, a small herd of reindeer appeared over the crest of a nearby hill and galloped across our field of view, cocking their heads as they past us and then just as quickly melting into the gloom of the opposite horizon. It is hard to judge distances here in this cold desert. An unusual rock formation in the distance might be small and quite close by or enormous and very far away.

I felt for a moment as if I had been transported back to the Pleistocene, as the landscape I was looking at was what much of Europe and North America would have been like at the end of the last Ice Age, though (other than the reindeer) there wasn’t any of the charismatic megafauna such as the woolly mammoth and the cave lions I would have had to concern myself with back then. Semi-domesticated, reindeer have sustained the local Sami people since ancient times and they are of the few creatures (other than snails) to manufacture the enzyme lichenase, enabling them to survive on lichen during the winter months.

How this delicate ecological balance will be affected by climate change is unclear but to my mind it doesn’t look good. Lichens exist in fairly specific temperature and humidity conditions and in Kilpisjärvi many are symbiotic with the birch trees, themselves a cold-dependent species. A continued warming trend in this region is bound to mean diminishment of suitable reindeer habitat. This has already occurred in North America, where the closely related Woodland Caribou has steadily disappeared from the southern portions of its range.

Standing in the middle of this iconic subarctic landscape, it is hard to imagine rapid changes occurring. For thousands of years, the processes shaping it have been gradual and incremental – the slow scouring of glaciers advancing and retreating, the infiltration of frost with its insidious heaving and splitting, the seasonal flows of meltwater into the lakes and rivers. The cold accentuates the sense of Deep Time here. Rocks dragged by ancient ice flows sit solemnly in place as if they stopped moving only yesterday. The sparse, slow growing vegetation is no match for the overwhelmingly geologic feeling of the place. Even minor disturbances stay visible for centuries.

But add even a small degree of warming and there would be potentially huge changes. Vegetative growth would ramp up, allowing trees to flourish in areas that were once windswept barrens. It is easy to imagine the slopes of Saana darkening as the Scotch Pine (Pinus sylvestris), now found only intermittently in the Kilpisjärvi area but quite common further south, finds conditions more suitable to it and becomes a dominant species. True tundra and the flora and fauna that depend on it could disappear from the area entirely.

lone Scots pine Fast-forward a little further and there could be a whole host of new species that find the once frigid environs of Kilpisjärvi newly tolerable. A good many of these are likely to be weeds, which thrive on man-made disturbance. Investigating the grounds around the research station, I soon found a small clump of English plantain (Plantago major) a cosmopolitan weed, dubbed the ‘white man’s footprint’ by North American First Nations, who noticed it growing wherever European colonizers had disturbed the original ecosystem. The humble plantain is just the beginning. I predict that larger weed species will soon be gaining a foothold at Kilpisjärvi; their seeds imported on tire treads or blown in with the wind.

I wondered how it might look here when Ailanthus altissima, a tree variously known as the ‘Ghetto Palm’ or ‘Tree of Heaven,’ moves into the Finnish subarctic. Originally from China, Ailanthus is exuberantly invasive, and has already moved into ruderal (ruin) ecologies throughout the world without any signs of stopping. This tree has the astounding ability to feed off concrete, allowing it to thrive in cracks in pavement, the roofs and facades of under-maintained buildings and pretty much any other place its myriad seeds are able to lodge themselves long enough to germinate.

Ailanthus trees As the global south becomes uninhabitable due to increasing drought, wildfire and relentless heat, it isn’t hard to imagine a newly temperate Kilpisjärvi becoming a major magnet for climate refugees, human and non-human. Higher annual temperatures, as well as attracting different flora and fauna, could make the cultivation of cereal crops a possibility and perhaps other kinds of intensive agriculture, now more characteristic of Central Europe. This could transform the wild, transhumance landscape into a ‘Kulturlandschaft,’ the subarctic wilderness giving way to ploughed fields, perhaps even orchards. There might be a property boom as the open range lands once suitable only for reindeer husbandry become hosts to cash crops and housing estates. The effect on the traditional Sami lifestyle would be incalculable.

A climate-changed Kilpisjärvi would be a kind of ‘hyperecology’– a co-mingling of adaptive, cosmopolitan weeds, perhaps a few resilient local organisms and a steady in-migration of biota from the south. Outside the national parks and reserves, post-climate change nature will have even less of a free hand. There is massive industrial development afoot for Lapland, particularly mining and its ancillary industries which threaten to blight vast tracts of the relatively pristine landscape with open pit mines, tailings ponds and processing infrastructure, which, as well as inevitably introducing all sorts of pollution will create a new terrain vague of slag heaps and factory wastelands. These ‘brownfields,’ ubiquitous in much of the industrialized world are the preferred habitats of the globally distributed ragamuffin flora: Ailanthus, Buddlea and Robinia, which find the toxic and impoverished soils to their liking.

Industrialized, intensely cultivated and densely populated, the Kilpisjärvi of the not-to-distant future might look strangely familiar to any present day resident of a more temperate latitude. Yet what has been predictable there for so long will soon become much more extreme. We may all find ourselves moving north.

But climate change isn’t likely to stop at this arbitrary point. The heat will likely continue to build, especially if mankind continues dumping carbon into the atmosphere and particularly if the much feared ‘runaway greenhouse’ effect kicks in. What then for Kilpisjärvi? The Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum that happened some 55 million years ago gives us a clue. In those days, the weather north of the Arctic circle was sultry and humid the year round. In addition to the Sciadopitys trees I described in my previous posting, vast swamp forests of Metasequoia and Taxodium spread out across the far north of Eurasia and North America, with turtles and crocodiles plying through the black water and mire. It would have resembled the bayou country of Louisiana or subtropical China, with snow and ice pretty much non-existent, a far cry from the frigid Kilpisjärvi of today, which can be icebound 200 days a year.

Eocene landscape Northern regions are well on track for a repeat of these subtropical conditions according to the most agreed upon climate change models, which predict an up to 4 degree Celsius rise globally by the end of the century, with a strong likelihood that changes in high latitudes will be more extreme. Though the biota will surely be more impoverished than it was in the Eocene, not having had anywhere near as much time to evolve, an anthropogenically tropical Lapland would be a mind-boggling yet disturbingly real possibility.

Though our species’ effect on climate can (and will) precipitate far-reaching changes in areas like Kilpisjärvi, there are many planetary processes playing out over which we have no control. The evolution of biota over Deep Time is as much happenstance as forward movement, with periods of great flourishing such as the infamous ‘Cambrian Explosion’ interspersed with ‘reversal’ or mass extinction, either organically or extraterrestrially engendered, which often obliterate whole classes of once dominant organisms and provide opportunities for minor ones to come out of the wings.

Past instigators of mass extinction have included: asteroid impacts, widespread volcanic eruptions with concomitant ocean acidification, even the evolution of photosynthesis by cyanobacteria, which released the toxic gas oxygen into the atmosphere to the detriment of the once dominant anaerobes. Any and all of these scenarios will likely play out again somewhere in the fullness of Deep Time, but barring the elimination of all life on the planet, it is worth speculating on the impact such upheavals would have on the vegetated landscape.

For example, what would happen if flowering plants, also known as angiosperms, dramatically declined, perhaps taken out by some pandemic or selective evolutionary pressure? They’ve really only been common since the Cretaceous and it isn’t hard to imagine Kilpisjärvi’s abundant so-called ‘lower’ plants – mosses, club mosses and liverworts, moving into the vacuum and attaining gigantic proportions, as was the case during in the coal swamps of the Carboniferous Period.

Neo-Kilpisjärvi with giant club mosses A reduction in the availability of sunlight due to volcanic ash or widespread dust storms could have equally bizarre consequences. With green plants and algea in decline because of the challenge to photosynthesis, there would be a selective advantage for fungi, which might take over Kilpisjärvi forming bizarre, colossal structures as they did during the Devonian Period, some 400 million years ago, and again during the mayhem of the Permian mass extinction. Whether our own species would survive under such extreme and alien conditions is an open question, but life of some sort is almost certain to find a way. Perhaps fungi will regroup to form the planet’s supreme intelligence. Some would say, they already have!

It is this last point that gives me a vestige of hope. We Homo sapiens are a problematic creature, a classic, invasive species that thrives on disturbance, tends toward monoculture and displaces competing biota from its habitat. Yet in the overall scheme of things we are likely to be a transient phenomenon. We will either precipitate our own extinction, (and if the surviving ecosystems of the planet could sigh in relief, they surely would!), or we will find a way to live within our ecological means and develop a more equitable arrangement with the fellow denizens of the biosphere. My stay at the Kilpisjärvi Biological Station offered me the ideal vantage point to consider this conundrum. What we are in now is not so much of a ‘watershed’ moment but more of a ‘timeshed’ moment!

Neo-Kilpisjärvi with giant fungi

Saana Fjell – Kilpisjärvi (in a warmer season!)

Sciadopitys in Helsinki Botanical Garden

What will the future look like?

A reasonable question and one which the human race has spent a long time thinking about.

I felt quite honoured to be asked to participate in this year’s ‘Field_Notes – Deep Time’ artist’s residency which took place this past September at the Kilpisjärvi Biological Station in the spectacular subarctic environs of Finnish Lapland. I was part of a working group led by my pals Liz Ellsworth and Jamie Kruse and our mission was to explore the concept of ‘Deep Futures in the Making.’

In many ways the bleak solitude of Kilpisjärvi proved the perfect vantage point from which to delve into ‘Deep Futures,’ both due to the majestic, timeless feeling of the landscape but also the unique vulnerability of the fragile ecosystem, which like others at high latitudes is likely to suffer disproportionately from the effects of anthropogenic climate change.

Perhaps biting off more than I could chew, I tasked myself with compiling what I called a ‘Speculative Botany’ for the future of subarctic Finland, based on what is there now and what is likely to happen in both the near and the long term.

The effects of global warming on arctic and subarctic ecosystems are already proceeding apace and in addition to the well known images of abject polar bears stranded on rapidly melting ice flows, there have been many other effects on northern biota. Here in North America, more southerly species such as robins (Turdus migratorius) and Pacific salmon are colonizing high arctic latitudes. A little to the south, vast tracts of Rocky Mountain forest are turning brown under an unprecedented onslaught of pine beetles, whose numbers are no longer kept in check due to milder winters and hotter summers.

So what about ‘Deep Futures?’

Environmental conditions are changing so rapidly that I frequently get the feeling I have already woken up Rip Van Winkle style in some deep future, where the things I have long taken for granted are no longer recognizable. Like the frogs that used to teem in the ditches of my suburban Toronto childhood. They are now disappearing worldwide, their once exuberant choruses silenced by a strange new fungal pandemic. The Western black rhino has just gone extinct – all of them. Gone. Wiped off the earth by relentless poaching. Neither you nor I nor anybody else will ever have a chance to see one. We blew it. And countless other species are on the brink of the same fate.

Climatologically, the obvious effects of anthropogenic warming are now everywhere and we are seeing weather events that are routinely more extreme than anything experienced in the recent past, though they have long been in our collective imagination. Reminiscent of J.G. Ballard’s dystopian 1960’s fantasies – ‘The Drowned World’ and ‘The Wind from Nowhere’ we now live in a world where ‘superstorms,’ extreme flooding and the disappearance of Arctic sea ice are the new normal

With the scientific consensus emerging that global temperatures will continue to rise by at least 4 degrees C by the end of the century, I wondered what might happen at Kilpisjärvi, which presently finds itself in a delicate mountain birch forest ecosystem, where normally the snow doesn’t melt until June. Already it is clear that with less severe winters, plant productivity and abundance in many far northern areas has significantly increased.

What novel re-groupings, permutations and combinations might occur as the climate of Kilpisjärvi warms up? Will the existing plants grow more rampantly or will they begin to find the new conditions intolerable and fade from the landscape? There are some basic principles I thought I could extrapolate from. For example, rapid climate change is likely to favour generalists, often weed species, capable of riding out a wide variety of conditions and quickly colonizing disturbed habitats. Cold-loving, habitat specific specialists will have a much more difficult time and would disappear from many of their more southern haunts.

the future of arctic fauna?

How long might it take for major changes in the biota to occur? There are so many things to consider. For example, birds can colonize newly habitats quickly, which in turn will be a vector for certain plants whose seeds travel long distances inside their digestive tracts to be deposited on new terrains. Wind borne seeds and spores are likewise rapidly distributed. We humans are perhaps the greatest agents for the dispersal of species, transporting them deliberately or by accident, through the shipment of goods, gardening and even on the soles of our shoes. The deeper the future, the more daunting the range of possibilities, so I thought it reasonable to start with the situation in Kilpisjärvi at the present day and project onward into deeper and deeper horizons of time, with a corresponding decrease in certainty.

I am an artist, not a scientist, so I knew my speculations would be more qualitative than quantitative, but I figured it was worth trying to extrapolate obvious trends and imagine how they might unfold in both the near and long term.

A few hours after first touching down in Helsinki and pleasantly catatonic from the jet lag, I took a long walk through the venerable Kaisaniemi Botanical Garden. It is a habit of mine to visit the botanical garden of any city that is new to me and I was curious to see what the Finns managed to cultivate at such a high northern latitude. And I wanted to establish some sort of a baseline for what would typically constitute northern flora. Admittedly Helsinki is a good deal further south than Kilpisjärvi but is nevertheless considered the world’s most northerly metropolitan area and I reckoned the climate of Kilpisjärvi would begin to drift toward that of present day Helsinki as the planet continues to warm. Established in the early 1800’s Kaisaniemi has the agreeable and lush historicity of an old, lovingly maintained park, a world within itself of specimen groves and steamy glasshouses, where the casual stroller or the committed anomophile can each commune with the diverse array of the botanically possible.

From the very beginning gardeners have always pushed the envelope of what can be cultivated in a given climatic zone and Kaianiemi is no exception. For example there is an enormous walnut (Juglans regia) tree, sprawling and laden with nuts far to the north of its usual more temperate haunts. I was delighted to see one of my favourite living fossils, the monotypic Sciadopitys verticella, commonly referred to as the Japanese umbrella pine, as it is now only native to a small area of Japan. Yet during the Eocene Thermal Maximum 50 million years ago there were whole forests of these trees in the vicinity of what is now Finland and the resin they produced was so ubiquitous it makes up the bulk of the area’s famous Baltic amber. During that long ago time, the average temperatures on the earth were extemely high, as high, in fact, as it is expected to rise again within this next century, due to man-made global warming. Could it be that Sciadopitys might one day hop Kaianiemi’s garden fence and make itself at home again in the forests around a newly tepid Baltic? I wonder…

In contrast to how compact everything generally seems to a North American traveling through Europe, the distances in Finland are quite vast. The day after arriving in Helsinki, I was en route on the seven hour trek to Kilpisjärvi, which began with a one hour flight north to Rovaniemi,‘the hometown of Santa’ and the capital of Lapland (not necessarily in that order), followed by a six hour bus ride on a two lane highway to almost the 70th parallel. As the scenery passed by and the tires hummed and the vegetation grew more sparse, we were able to acquainted with each other and start thinking about how we might address a topic as vast as ‘Deep Time.’

On a more prosaic note: I loved the bizarre and über-Nordic aesthetic of the coffee-shops in roadside Lapland, a few of which we were able to sample on the bus ride to and from Kipisjärvi. Amazingly, there is a pension for Thai food up here. Their secret ingredient – reindeer meat! And by the way, the wood carvers are definitely on drugs – perhaps some taiga version of the magic mushroom… Check out the whacky wooden dwarfs that are the regional specialty. The carving style out-Seusses Doctor Seuss! Oh those long winters! I think I understand the flying reindeer now…

An hour or so from our destination, and the landscape morphed into a vast, misty expanse of exposed rock, russet heath lands and dwarf birches, their branches stripped of all but a few remaining yellow leaves despite it being only mid September – still, as far as the calendar is concerned – summer! When we finally pulled into the Kilpisjärvi Biological Station it was almost dark. The air had a thin, alpine quality about it and the massive silhouette of the Saana fjell loomed over us like some giant recumbent beast. We were told we’d be climbing it the next day and we collapsed into our beds…

Sanaa socked in with cloud

bonfire of the crocodiles

“What remains is the red wind in the field with the name of the rose upon its lips”

(Russian metaphorical poem)

It’s an unspecific hour; morning probably, but not according to my biological clock, which is still mired in the mudflats of sleep. I’ve just touched down at Helsinki Vantaa Airport and outside the glass curtain walls, an anemic subarctic sun washes across tidy parking lots and spills over the crowns of the birch trees that quiver golden against the cold blue vault of the Nordic sky. It’s only mid-September yet fall has locked itself in.

The life force seeped out of me somewhere over Greenland and I need somehow to absorb enough caffeine to re-start my misfiring nervous system and begin to part the skeins of translucent eye plankton that drifted across my field of vision since I stumbled off my Finnair flight. Not that Finnair is a bad airline -far from it! My flight had none of that Nilodor meets stale sweat and leatherette odor that greets the nostrils on the cheap airlines I usually take, where the business model increasingly seems focused on finding new and exquisite tortures for us coach class customers so that we’ll start coughing up money for what used to be free:

Want to eat something? Check baggage? Board in a timely manner or sit in a seat that won’t cut your circulation off? It ‘ll cost you. The limits of human endurance have already been reached though I can’t help wondering what the next iteration of airline indignity will be. Perhaps a charge for using the toilets or maybe getting rid of the seats entirely and piling us up like sacks of UNHCR rations to be lashed into the hold with bungee nets.

I try to get my mind off these things as I settle into the first coffee shop I see, maneuvering my espresso and wheelie bag toward a vacant table. It is quiet and ordered here. The men’s room is awash with simulated birdsong and the beautifully designed faucets and the hand dryers actually work. There is none of that under-serviced, held together with duct tape and gum quality that pervades most American airports these days.

There’s not many people in here – some airport guys in orange safety vests and a large, older black woman in a black raincoat and multi-colored headscarf. She seems to be wearing a lot of layers.

On the TV monitor above us, there’s a morning talk show in progress, which the cuts to the image of a helicopter pulling a very large and very dead crocodile up from a muddy waterhole with a long steel cable. The Finnish celebrities discuss this for a moment as the shot goes to a close up of the cable tightening around the monstrous animal’s neck and then pans out to the silhouette of its great carcass swinging back and forth beneath the helicopter until both are engulfed into the vast pink inflammation of a tropical sunset.

The guys in the orange vests next to me have stopped talking and seem riveted to the screen.

The shot now is of the mountainous dead reptile slumping down in front of a group of park ranger type people dressed in khaki safari gear. A couple of burlier guys unhook the cable and the helicopter rises up out of the screen and we zoom in on several of the ranger people clamber over the tree trunk sized corpse with calipers measuring tapes and syringes. A dour looking guy in a blue uniform talks into a walkie talkie and looks on. A young ranger woman aims the lens of her large camera at the once mighty creature’s head and we cut to a close up of the sad, shrunken eyelids, which have deeply into the sockets underscoring that it has been dead for a long time. A florid faced man with a large pair of pliers pries out one of the crocodile’s enormous scales and drops it into a jar of liquid.

This seems somehow cruel and disrespectful but the crocodile is dead after all.

The scene changes and we see more dead crocodiles this time scattered like logs along a wide river bank. There are dozens of them and many are belly up, their lighter colored undersides looking swollen and puffy in the high contrast light, the armored skins seeping sickly death fluids, though this is only visible for an instant and perhaps I am extrapolating. Something is clearly killing those crocodiles and everyone seems to get that. It is being made very obvious. Carrion birds circle and land to prod haphazardly at the carcass but they don’t look too enthusiastic at the quality of what lies before them. Perhaps the crocodiles are poisoned or the corpses are not appealing to them or just too far gone. Too far gone for carrion birds? I find that hard to believe. The camera zooms in on some foot tracks and pans toward another muddy pool where we see the corpse of a smaller crocodile, six feet or so in length, festering in stagnant water. ‘It has crawled off to die here’ the narration must be telling us, albeit in Finnish, which for me is completely inscrutable, and anyways the sound is turned way down.

A ranger guy in very short khaki shorts (what is it about tropical Caucasians and their really short shorts?) loops a cable under the smaller creature’s forelimbs and watches it get winched up, deus ex machina, by the helicopter hovering overhead, which then ascends as before, dangling its payload against the picturesque, distant thunder clouds, pregnant with rain. This smaller croc gets dumped into the back of a pickup truck.

In the next shot we see a very large pile of dead crocodiles, which have been accumulating at some kind of a staging area. The helicopters keep arriving bringing more of them in. A couple of grad student type women are stacking logs and branches into a conical pyre type arrangement. We see a section where the crocodiles of all shapes and sizes are being dragged toward the pyre, the smaller ones being dragged by their tails the larger ones hauled in on buckets of heavy earth moving equipment or pulled in winches. The camera zooms in on gasoline being poured on the pyre. We pull out to a long shot of the burning pyre with its oily smoke roiling into a peach colored sky. People are milling around beside the conflagration in a kind of agitated way though some are just standing there with their hands on their waists.

It is night time now and we see a crocodile, apparently alive with its jaws fastened together with heavy duty duct tape. We cut to a flashback of it being pulled out of a waterhole and it is wrapped up in a painful-looking ensnarement of ropes and cables, which makes me think of Japanese rope pornography and its trussed-up women, only this time it involves an antediluvian reptile, so there is nothing sexual about it, at least not obviously so. With an electric drill, a man bores a hole through one of the larger scales on the dorsal crest through which he loops some kind of an electronic tracking device. This crocodile will probably never enjoy privacy again, I imagine, but this is probably ‘for the good of the species’ or something like that. The men finish calibrating the tracker and unfasten the ropes before gingerly backing away. The crocodile stays motionless for a moment then explodes into the dark water in a burst of spray. The men wander off with their flashlight beams bobbing up and down against blurry vegetation and everything seems calm for the moment.

The celebrity panel starts their banter again and the spell of the program is broken. The guys in the orange vests resume their gruff, unintelligible man talk and I can’t tell at all whether they were appalled by what we all just saw or are just talking about work. The black woman with her many layers of clothing stands looking at the screen a moment longer then gives out a long, sad sigh and slowly walks away.

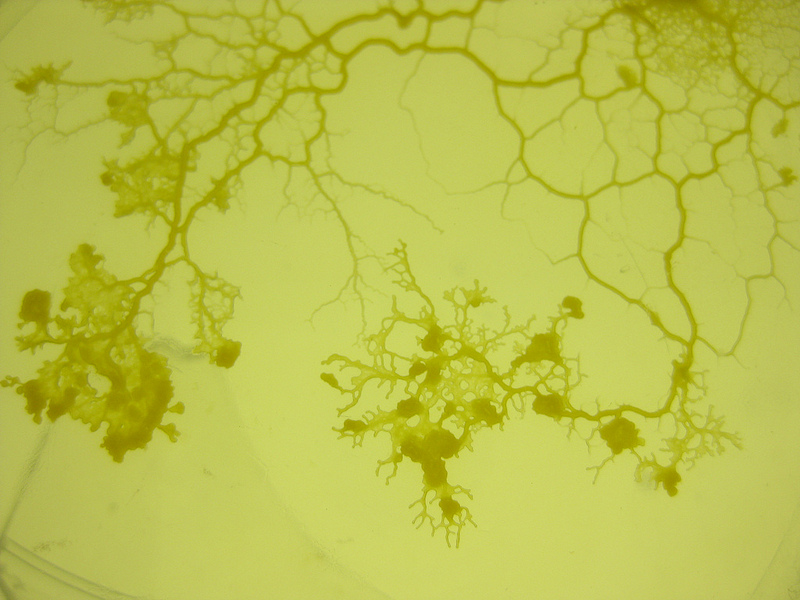

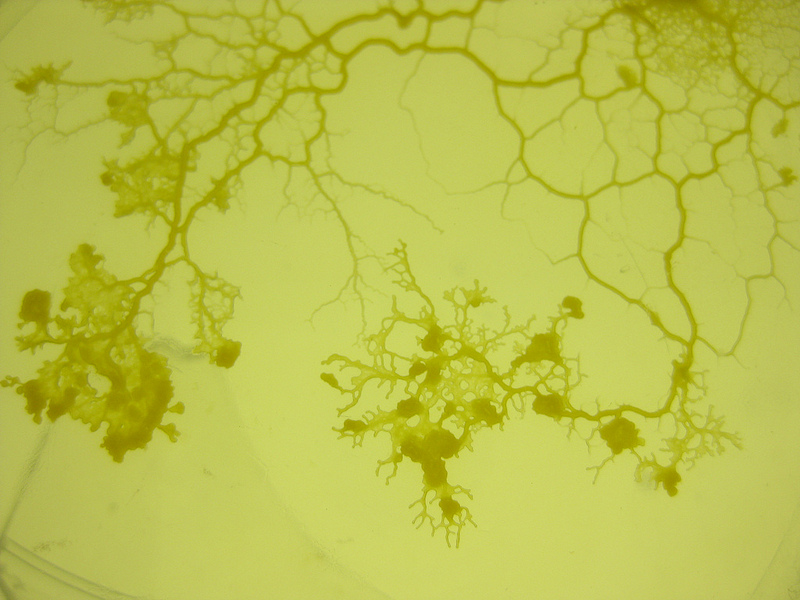

Fuligo septica in my back yard

Physarum polycephalum close up

Those of you who’ve followed my blog for a while will know I am fascinated by the intellectual capabilities of slime moulds…

This is the time of year when the dark coniferous forests near my house get brightened up by their white and yellow blobs of sentient goo. Around here, they are mostly the common slime mould Fuligo septica – otherwise known as ‘Dog Vomit slime mould,’ a rather harsh name, in my opinion, for such an engaging life form.

Far from being vomit or mould, these slimy masses are actually swarms of social amoebae that have combined their protoplasm and nuclei into a single super-organism called a plasmodium.

Once formed, the plasmodium creeps along the forest floor until it reaches a tree stump or log, at which point it climbs to a high enough vantage point from where it releases its spores into the slightly more active air. These drift, land, and eventually germinate into another generation tiny amoebas that one day will seek each other out, meld together and then start their complicated social migration process again.

This is all very fascinating, but the reason slime moulds have been the subject of such intensive research is that their plasmodial masses show an uncanny ability to solve computational problems – which is all the more remarkable given that slime mould has neither brain or a nervous system and its constituent amoebae are about as rudimentary a life form as you can get. But when large numbers of these simple beings are networked into a swarm, the principle of emergence takes over and we begin to see a unified intelligence. The rules governing emergence are fairly simple – as long as each individual is aware of and able to exchange basic sensory information with its neighbours, stimuli can be transmitted throughout the network, which can then react as a sentient whole, flowing toward attractants or away from danger.

This simple yet powerful mechanism is behind the flocking of birds, the flow of traffic and the evolution of memes on the internet. It is a non-hierarchical, ‘ur’-intelligence, an organizing tendency imbued in the very vibrancy of matter itself.

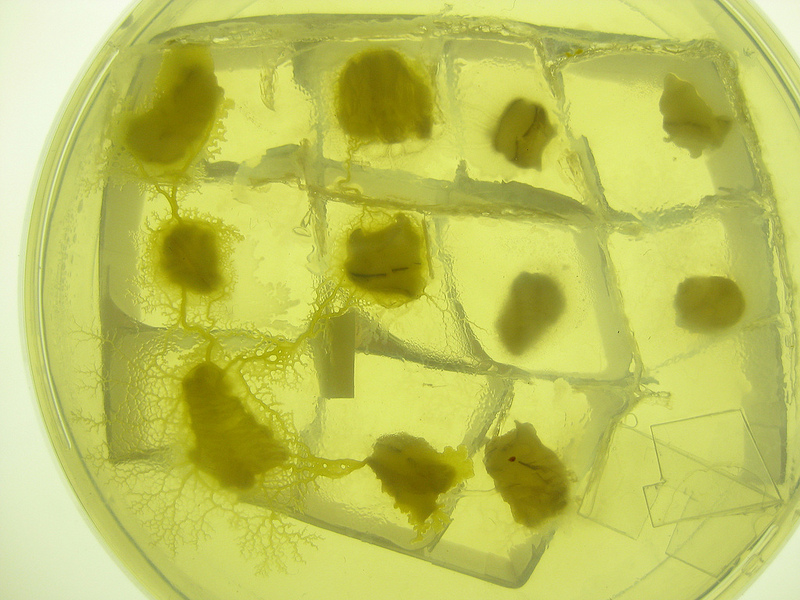

The lab rat of the slime mould world is the easy-to-raise species Physarum polycephalum and as such it has been the subject of much experimentation. Lured by oatmeal flakes, Physarum can outperform robots in solving mazes and it will figure out mathematically complex problems such as how to most efficiently connect an arrangement of arbitrary points, making it astonishingly good at designing highway networks and other mesh-like systems. Though brainless, Physarum has a rudimentary spatial memory. It recognizes where it has already explored by sensing the slime trails it has left behind, allowing it to focus its foraging energy on covering new ground.

Inspired by my time hanging around with the bio-geeks at Brooklyn’s GENSPACE, I decided to put old Physarum to the test by giving it some problems I thought worthy of its impressive powers.

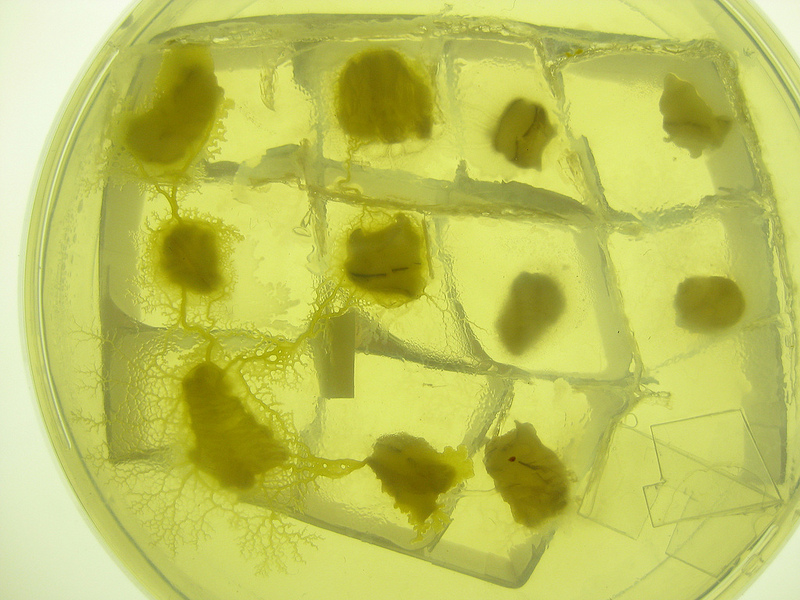

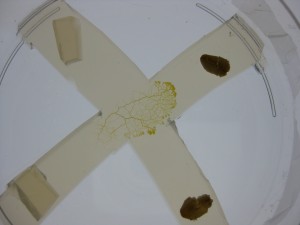

slime mould navigating a model of an IKEA 1) The IKEA vexation:

For years I have been irked by IKEA stores. What is the most efficient way to navigate through one of them? I find IKEA to be especially frustrating and always have had trouble finding my way toward the exit without being overcome by an anxious ‘trapped’ feeling. For me, IKEA is prime habitat for what it called the Gruen transfer – a deliberate architectural strategy aimed at disorienting people in shopping malls; an invocation of spatial confusion that makes us lose track of our original intentions and buy stuff we don’t need. I wondered if the slime mould could resist such distractions and efficiently find its way through an IKEA without getting sidetracked? To put this to the test, I built a tiny petri-dish sized model of the floor plan of the IKEA, modeled on the store in Richmond, British Columbia, which is more or less typical. Each department was baited with an oatmeal flake and I plunked a little bit of Physarum culture down near the store’s entrance to see what it could do.

slime mould says ‘yes!’

second choice ‘hazy!’

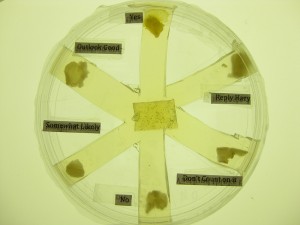

at the moment of ‘yes or no?’

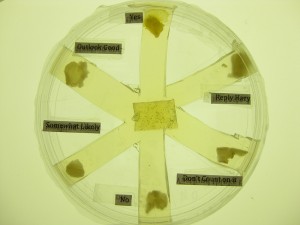

2) The Future is out there:

Decisions involving the future are hard for me to make, especially if there are a lot of equal seeming options. Throughout history, we’ve consulted soothsayers, fortune tellers and ouija boards in hopes we might get some guidance on how to choose between those many forks we encounter in life’s road. I’ve often despair and then make a seemingly random choice. If slime moulds are so good at solving problems in the here and now, how might they do in sussing out what hasn’t yet happened? Could they help me ‘Magic 8-Ball’ style make decisions on what to do next? Well, I was a little too clumsy to build a proper ‘8-Ball’, but I managed to make a reasonably convincing ‘6-Ball’ simulacrum, by cutting six (approximately identical) radial paths into the agar of a petri dish and having the slime mould choose which one it wanted to go down. I baited each ‘choice’ with a flake of oatmeal and labelled them: ‘yes,’ ‘no,’ ‘outlook good,’ ‘reply hazy,’ ‘somewhat likely,’ and ‘don’t count on it!’ I’d ask the slime mould a (secret) question then wait a few hours to see what it decided.

Well those of you who have had scientific training are probably about to bust a blood vessel about now, but bear with me!

ballistic behaviour Perhaps predictably, the IKEA ‘maze’ problem was quickly solved by Physarum. It relentlessly streamed from one ‘department’ to the next in search of its oatmeal rewards and within a couple of days, it arrived at the exit hungry for more. This is a very basic slime mould-solvable problem. Physarum tends to behave in what is called a ‘ballistic’ manner; once they have sensed a stimulus they will try to flow toward it taking the most direct route possible.

Except when they don’t

Because unlike a non-sentient being, slime mould will often abort its migration toward an attractant, if it senses a rival has gotten there first. Sometimes though, competitors will merge into one happy super organism and share the the love and the bounty.

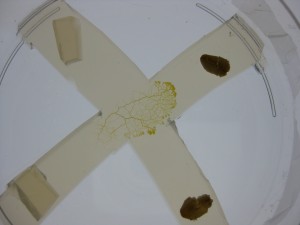

inputs A and B seeking oatmeal

A and B combining to one output

This makes for some interesting possibilities for ‘non-digital’ logic. Let’s say we place slime moulds, (let’s call them ‘A’ and ‘B’) in each of the two forks of a ‘Y’ shaped path and put an oatmeal flake in the remaining leg. If the slime moulds were to behave consistently that is to say ‘digitally’, you would have the basis for what is called an Exclusive ‘OR’ gate, a common component of computer logic. There has been some great research done on this by Andrew Adamatzky at the University of the West of England.

Given the slime moulds’ usual aversion to the presence of a rival, the one that gets to the bait first will dissuade the other. So in logic gate terms the presence of ‘A’ or ‘B’ (the inputs) will generate an output, i.e. either ‘A’ or ‘B’ gets to the oatmeal.

‘A’ and ‘B’ can’t both reach the oatmeal because the presence of one will (most of the time) repel the other, so the gate is considered ‘exclusive.’

But because slime moulds, though simple, are living things, with their own agency, they don’t always do what we expect. When the slime moulds ‘A’ and ‘B’ break convention and flow together to share the oatmeal, the logic gate becomes ‘non-exclusive,’ i.e input ‘A’ or ‘B’ or both can appear as outputs. Sometimes even that doesn’t happen and a slime mould gets distracted and decides to loiter around the perimeter of the petri dish, boycotting the experiment despite the presence of oatmeal. Who knows why? Are they following their bliss? Or are they just confused? To my mind, these ‘exceptions’ to the behaviour we deem ‘logical’ are the most interesting results. If we develop a new class of biological computers based on slime mould logic, the outputs generated might have a charming and useful variability. This could be used to more closely emulate the real world ‘twitchiness’ of such social phenomena as how people behave in the marketplace (they don’t always act rationally or in their self interest), or how they participate in riots or elections, which are also less than rational processes.

this time- both outputs are generated! And as for predicting my future, the slime mould oracle was initially quite decisive. It answered my first (secret) question with a resounding ‘Yes,’ but then started creeping around to investigate other nearby possibilities. To me that seems like a perfectly reasonable approach.

Vancouver Island highway scene At this ardently bright juncture of the year, there is something quite delightful about gazing up into the cool, rustling canopy of overhanging trees. It is a very deep memory for me. I must have been an infant, lying on the back bench seat of my parents’ old Buick, gazing up through the rear window at the dark tunnel of foliage billowing overhead, flashing here and there with orange bursts of interpenetrating sunlight. The dust from the road was starting to smell like the softer evening version of itself and the roadside insects, cicadas probably, hissed in their enormous, invisible numbers.

In my recent journeys between England and Canada, I have been struck by the contrast in attitudes toward what one might call ‘arboreal heritage’ between the two places. When driving on Vancouver Island I am inevitably torn between throwing up and crying whenever I see, as I almost always do, some of the last old growth Douglas firs (Pseudotsuga menziesii) getting hauled down the highway on some logging truck. Their rate of felling has been accelerated recently by a growth in demand from overseas, particularly Chinese, markets and the provincial government’s stupendously short-sighted decision to relax restrictions on the exporting of raw logs.

Each one of these ancient trees is a monument to the passing of centuries, a lynchpin around which complex ecological processes have evolved and yet we are losing the last primeval stands right at this very moment. To see one of those loaded trucks is like witnessing the carcass of a blue whale or a rhinoceros trucked off to a dog food factory but what more is there to be said? We have pointed our fingers yet the market economy has triumphed and the trees continue to fall. Soon all there will be left is a lingering sense of shame until that too eventually disappears. Outside a few relic specimens that happen to find themselves inside parks, the ancient fir groves of Vancouver Island will soon be obliterated. The Island Timberlands company continues to be a key player in this campaign of ecological extermination and is specifically targeting the large old trees on its vast private holdings to service an international market growing all the more lucrative as the global supply of first growth trees plummets.

this linden (lime) tree has been coppiced since at least the 13th century! While British Columbia has been embarrassingly and heartbreakingly remiss in its protection of Vancouver Island’s ancient firs, there are pockets of silvicultural enlightenment elsewhere in the world that can restore one’s faith in humanity. Last month Ruth and I spent a memorable afternoon at the Westonbirt Arboretum and got introduced to some of its innovative programs by director Simon Toomer. It may sound odd, but one of the highlights of our tour was seeing the manifold stumps of a recently harvested lime (Tilia sp.) tree, which has been harvested using the coppicing technique since at least the 13th century. The tree itself, which has spread out into about 60 individual stems, could be over a thousand years old! Coppicing (periodic cutting from regrowth regenerated from stumps or ‘stools’) is an ancient technique, suitable for a variety of mostly broadleaf trees, which paradoxically causes them to live much longer than if they were allowed to grow uncut. The practice periodically opens up parts of the forest canopy, allowing for an influx of light and a host of species dependent on brighter conditons, which enhances diversity in the forest, without massacring the entire structure over a large landscape as is done during industrial clear cutting. In British Columbia, it would definitely be worth testing out large-scale coppice management of Big-leafed maple (Acer macrophyllum) and Red Alder (Alnus rubra), both of which are capable of rapid regeneration from stumps and which have the potential to produce a range of sustainable wood products.

Westonbirt is also engaged in pioneering research on how forests will be affected by climate change and have initiated a series of long term trials of trees, hailing from a spectrum of locations, from the southern to northern parts of their present day ranges. If conditions continue to heat up, it is likely that trees evolving in more southerly latitudes will increasingly thrive within the British landscape, while more cold-adapted ones will only do well at higher latitudes and altitudes.

Back in British Columbia, I am beginning to draw similar conclusions. Though still in its early stages, the initial results of my Cortes Island ‘Neo-Eocene’ project indicate that some tree species now native to more southerly latitudes, such as Coast Redwood (Sequoia sempervirens) and Metasequoia (Metasequoia glyptostroboides) might actually grow faster under West Coast Canadian conditions than varieties currently prescribed for re-forestation, such as Western Red cedar (Thuja plicata). The difference is likely to intensify as northern climates continue to heat up. Climate warming is already causing massive mortality in northern populations of the native yellow cypress/cedar (Cupressus nootkatensis), because spring snow cover is no longer thick enough to protect their delicate roots from late frosts.