|

|

The Sea and the Desert is a chapter in Henry David Thoreau’s chronicle of his extensive ‘sojourning’ around Cape Cod in the 1860’s.

We might think of rising sea levels and creeping desertification as uniquely contemporary symptoms of anthropogenic climate change but Thoreau noticed them way back in his day, recording with his characteristic eye for detail, a great many meteorological, ecological and human phenomena that together create the shifting territory of the thing we call ‘the Cape.’

This desert extends from the extremity of the Cape, through Provincetown into Truro, and many a time as we were traversing it we were reminded of “Riley’s Narrative” of his captivity in the sands of Arabia, notwithstanding the cold. …. In one place we saw numerous dead tops of trees projecting through the otherwise uninterrupted desert, where, as we afterward learned, thirty or forty years before a flourishing forest had stood, and now, as the trees were laid bare from year to year, the inhabitants cut off their tops for fuel.

Though Cape Cod has been in a state of constant flux ever since it was first bulldozed into place by the glaciers of the last ice age, there is a certain poignancy to its more recent, post-colonial history, as one of the first landfalls of European incursion into North America. The successive human waves that broke upon its shores left their own layers of deposition–the accumulated strata of hopes, ambitions and failures are embedded all over the landscape, if one knows where to look.

Thoreau encapsulated the protean quality of the Cape so beautifully:

The sea-shore is a sort of neutral ground, a most advantageous point from which to contemplate this world. It is even a trivial place. The waves forever rolling to the land are too far-travelled and untamable to be familiar. Creeping along the endless beach amid the sun-squall and the foam, it occurs to us that we, too, are the product of sea-slime.

It is a wild, rank place, and there is no flattery in it. Strewn with crabs, horse-shoes, and razor-clams, and whatever the sea casts up,—a vast morgue, where famished dogs may range in packs, and crows come daily to glean the pittance which the tide leaves them. The carcasses of men and beasts together lie stately up upon its shelf, rotting and bleaching in the sun and waves, and each tide turns them in their beds, and tucks fresh sand under them. There is naked Nature, inhumanly sincere, wasting no thought on man, nibbling at the cliffy shore where gulls wheel amid the spray.

There is still a seething, hissing quality about the place; a sort of fragility too, as if all the quaint human infrastructure, the architectural bric-a-brac of National Seashore information kiosks, the tourist shops and thriving gay bars of Provincetown, the upscale beach houses and black-topped roads could all be washed away with the slightest turning in the weather.

Given my interest in disturbance ecologies, I was thrilled to be offered an artist’s residency at one of the Cape’s oldest houses, at a place called Phats Valley near the town of Truro. I was joined there by my friends and collaborators, Liz Ellsworth and Jamie Kruse of the New School, whose artistic practice focuses primarily on matters geologic and the study of deep time, and who both have had a long term aesthetic engagement with the landscape and culture of the Cape.

We set ourselves a mission of a contemplative nature: to endeavour to capture something of the essence of our locality in its current, Anthropocenic, moment; to attune ourselves to its ephemerality by simply walking, pausing and observing. Our inspiration was the 17th century Japanese poet Bāsho, who set set out on a five-month journey, documented in his poetic chronicle: Narrow Road to the Interior. While traveling, Bashō drew upon and modified the traditionally collaborative haiku practice known as renga, which incorporates sensations of place, events and allusions to literature, history and myth. Renga, in its most basic form, is written by multiple authors who link their verses, building upon each other’s words under the inspiration of the environmental and social contexts of the moment (the trees in bloom, the stage of the moon, and who else is present at the renga party.) At its best renga embodies the impermanence, the ‘this-ness,’ of an instant in time.

Deleuze gave (this) ‘this-ness’ a name, calling it haecceity, from the Latin ‘to behold.’

A season a winter, a summer, an hour, a date have a perfect individuality lacking nothing, even though this individuality is different from that of a thing or a subject. They are haecceities in the sense that they consist entirely of relations of movement and rest between molecules or particles, capacities to affect and to be affected.

A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia (with Felix Guattari)

With the inspiration of Thoreau and Bāsho to guide us, Liz, Jamie and I set out under the great blue vault of a magnificent late summer sky to begin what the theorist Jane Bennett refers to as microvisioning, in reference to the way Thoreau practiced his art of engaged observation and deep attention–not an overly probing or systematic scrutiny–but rather more of a perceptual wandering; a seeing without preoccupied looking.

Go not to the object; let it come to you…

(Thoreau’s Journal 4:351)

From our base at the verge of time and space on the margin of Phats Valley’s picturesque salt marsh, we sojourned to various nearby localities, making a daily practice of easing into our immersive awareness, starting our sessions with conversation and tea before we delved into contemplative observation and ultimately, the generation of the renga stanzas. These take the format of (5,7,5,7,7) syllables. .

(5, 7, 5,7,7)

My gaze it returns

To dying rays of sunshine

A vulture circling

In an otherwise empty

Blue anthropocenic sky

(For example)

Liz and Jamie’s long-standing relationship with the Cape complimented my situation of never having been there before, and writing together gave us the chance to meld our sensibilities and subjectivities, our responses to the environment and the material conditions we encountered; both in the perfect individuality of the moment and in the larger geologic and historic frameworks where these moments seem to float. I had just been at the massive (600,000 person strong) People’s Climate March in New York City–a watershed moment in the public acknowledgement that something ought to be done–but what did it all mean? Through renga, I hoped I might get a little closer to some kind of understanding

Our daily practice evolved as a kind of meta-narrative, a record of our pausings, when we made the time to observe and acknowledge the this-ness of a given moment within the multiplicity, or white hiss, of all the other moments, extending through space and time.

We ended our residency with a public renga writing party and shared a lovely afternoon with a group of intrepid poets, who composed the renga with us on large rolls of paper, tacked to the outside walls of the historic Phats Valley headquarters. The whole event is nicely documented here on Liz and Jamie’s blog. Thanks in particular should be given to the residency coordinators Ann Chen and Davey Field of the Nomadic Department of the Interior, who made our residency possible. The house, dating back to the American Revolution, has been in Davey’s family since the early 1960’s and staying there was truly a delight, though when I first walked in, about to spend the night in it alone, I could sense there was some kind of ghost or other (palpable though not visible) presence sharing my abode. As is my custom, I introduced myself to the empty yet somehow electrically charged air of one of the attic bedrooms, and from that point on a cosseting calmness descended and I was able to sleep most soundly. Ghosts very much need to be acknowledged I think, and might appreciate a certain degree of politeness. After all, who knows what it might be like for them having to put up with us clattering around like boors in the overlapping domains of our reality?

Be it the accumulated spirits of the deceased inhabitants or the drifts of plastic waste piling up on its beaches, Cape Cod is all about layers. It is a shifting palimpsest that appears to will itself into being; reconstituting itself out of the products of its own decomposition and perpetually reemerging as the new Cape, out of the shifting, drifting sediments of the old. With its vitality, agency and interconnectivity to the deep, swirling cycles of geology and weather, Cape Cod is truly a hyperobject.

In order to engage such an ephemeral subject at a given instant, we thought it helpful to embrace Thoreau’s concept of ‘incomplete learning,’ an experience akin to what one feels when starting a foreign language, when the sounds and meanings are not yet clear and still largely perceived as an undifferentiated continuum–with the inherent capacity to startle, yet without being subsumed into the banality of explicated meaning.

‘Not until we have lost the world do we begin to find ourselves’

(Thoreau, Walden 171)

Jane Bennett makes reference to this non-judgemental, rather Zen-like practice of observation, in her 2002 ‘Thoreau’s Nature: Ethics, Politics in the Wild,’ where she builds a convincing case for his surprisingly post-modernist tendencies.

mineraloids The Phats Valley house and its immediate environs exist as a kind of microcosm for the cycles of ebb and flow, erosion and sedimentation that so define the ‘Cape-ness’ of the Cape. The salt marsh is bisected by an artificial ithmus– the abandoned causeway of the Cape Cod railway, now the domain of sombre pitch pines and scraggly sumachs. In its rubble, I found anthropocenic mineraloids– fragments of slag, coke and brick constituting the geologic stratum of a once thriving Steam Age civilization that existed here during the 19th century. The quaint house, archetypical Americana, with its prim clapboard and gnarled, rustling trees, now seems a world away from the spectre of machinery. The long driveway floods during the higher tides, adding to the sense of splendid isolation.

Yet the view from the front door, which now looks out over an olive-coloured expanse of soughing cord grass and wheeling marsh birds, was once very different; the railway passed by just a few feet away, and I can imagine the chugging, clanging locomotives vibrating the windows of the parlour, backlighting the curtains with a roiling orange glow as they pulled their squealing train cars on into the magnetism of their destination.

That is all long gone now of course–another layer obscured by more recent sediment, continually accreting. The topmost strata is unmistakable in that it contains massive inclusions of discarded plastic, the most ubiquitous material of our age. In the relatively short time of its existence, plastic has spread throughout the biosphere, substantial parts of which, particularly in marine environments, can now legitimately be called the plastisphere, as organisms have already adapted to the problematic material by colonizing it and breaking it down into an even greater multiplicity of substances potentially harmful to man. Indeed, Plastics “R” Us!, as water-soluble plastic chemicals like bisphenol A (BPA) and flame retardants already circulate in all of our bloodstreams.

At Phats, the plastisphere is most visible in the zone of flotsam deposited at the high tide line. Plastic dominates this territory in a surprising variety of material expressions, creating an overall aesthetic experience that borders on the beautiful or the repulsive, depending on what frame of mind one is in. I include some photos of these happenstance assemblages at the start of this post.

Poking around those drifts of discarded polypropylene, polyethylene, styrene, vinyl, polycarbonate and nylon, I wondered what will form the stratum of the next geologic age? Will it be the ashes of human extinction that mark the dawn of the post-human, the way the K-T boundary delineates the quick and brutal end of the dinosaurs? Or will we be someday heralding the age of the neo-human, having somehow morphed into a species with greater sensitivity to the material realities of the planet on which we evolved.

Whatever will come next?

Whoever?

North Troy NY brownfield savanna

safari into the Williamette Cove brownfields

Those of who call ourselves ‘environmentalists’ have a tendency to imagine a prelapsarian wilderness that once was pristine and then became progressively defiled and diminished through the carelessness of humankind. But the earth had been through many environmental catastrophes long before we came along– though this doesn’t exactly excuse us from our manifold sins. The infamous Chixculub asteroid impact suddenly ended the long reign of the dinosaurs and the more insidious yet equally catastrophic evolution of photosynthesis deep within the cells of certain cyanobacteria contaminated the earth’s early biosphere with oxygen– a fatal poison to the majority of organisms present at the time, resulting in what is now known as the oxygen catastrophe, a mass die-off of the earth’s biodiversity and a climate change event that froze the planet in the longest snowball earth episode in geologic history.

What is unique in the present (Anthropocenic) moment is that we know we are causing a massive and likely suicidal ecological crisis and yet choose not to do anything about it. Here we are at the tail end of 2014 with atmospheric CO2 levels higher than they’ve been for 800,000 years and the 6th mass extinction accelerating to the point where the earth has lost half of its wildlife species in the past 40 years. Political leaders, particularly those of oil rich countries like my native Canada either willfully ignore the scientific consensus or in the most egregious cases, (again Canada), actively censor the findings of scientists and even weather forecasters. Because a little knowledge can be a dangerous thing. Or is it?

In a recent video, Žižek makes the perhaps startling case that there is considerable poetry in our present situation, that is to say, our disavowal, our state of knowing that something is true and yet acting as if it wasn’t. He argues that to “truly love the world, we must love its imperfections,” including, presumably, the ones for which we are directly responsible. “In trash,” he declares “is the true love of the world,” a sentiment similarly observed by a Zen priest in the masterful little documentary, Tokyo Waka, which explores the world of Tokyo’s ubiquitous and trash loving crows. To be more precise the priest observes: “In trash is the residue of desire,” a sentiment perhaps less direct but still elevating garbage to a kind of reified affection.

To follow that logic, when an entire landscape becomes trashed, it should be particularly worthy of our love and it was in this spirit that I embarked upon my summer explorations…

But first some background: The Superfund was originally set up in the America in 1980 to identify and facilitate the cleaning up of the country’s most hazardous waste sites. In theory this might have created sufficient funding and legislative willpower to deal with this dangerous and unhealthy problem but between partisan politics and bureaucratic ineptitude, implementation fell far short of what was needed.

Though most people would want steer clear of toxic wastelands, I wanted to see if there were any adaptive ecological processes operating there that might be transforming these zones of exclusion into useable habitats. I had the strong sense that conventional ecologists and environmentalists might be missing something very important, that nature was capable of doing an end run around our destruction, if only we would get out of the way. My summer safari took me to sites on both sides of the continent–Troy, NY and Portland, Oregon–and what I observed there gave me some hope and insight into nature’s surprising ability to colonize the messes we have left behind.

I was invited to Troy by my pal Kathy High for a collaborative investigation into the area’s extensive brownfields. Once known as the ‘collar city’ for its shirt, collar and textile production, Troy is considered the birthplace (and graveyard?) of the American industrial revolution. A fortuitous confluence of rivers made it possible for early factories to harness abundant mechanical (and eventually hydroelectric) power as well as to cheaply transport products and raw materials. Like so much of America’s industrial heartland, the area has suffered from economic decline and many of its once thrumming factories lie in ruin in within highly contaminated terrain.

Some of the worst sites are situated along the banks of the picturesque Hudson River, which transitions here from tidal to freshwater, the end of a long estuary. Downstream, all of the Hudson is classed as a Superfund site because of extensive contamination by PCBs, a potent carcinogen, dumped for decades by the General Electric Corporation as a byproduct of manufacturing transformers and other electrical components. PCB’s are a persistent organic pollutant (POP) that bioaccumulate in the river’s fish, making many species unsafe to eat–including the reputedly delicious striped bass that spawns nearby at the junction of the Hudson and Mohawk rivers.

chimney swifts over North Troy Despite being a very degraded ecosystem Troy’s former industrial landsa are full of surprises. As part of a summer youth program, I led a ‘bio blitz’ of a community garden that had been established on a brownfield site near the Sanctuary for Independent Media. It wasn’t long before we found a magnificent stag beetle hiding in the rotting stump of an (invasive! exotic!) Ailanthus tree. High overhead, chimney swifts traced their invisible arabesques into the topaz air of the summer evening. This species, has long adapted to human presence and as indicated by its common name, makes its nests in disused chimneys. The chimney swift is a close relative of the Vaux’s swift, which puts up a spectacular display every evening as great clouds of the birds funnel into in a large chimney at the Chapman School in Portland, Oregon.

A local Troy resident told me she had recently found red-backed salamanders under debris in her backyard yard, situated quite near some of city’s most contaminated industrial sites, with nothing that might be deemed ‘intact’ woodland anywhere in the vicinity. With the sharp decline of amphibians worldwide, even in protected national parks, it might seem surprising to find them surviving in such anthropogenically disturbed habitats but this is consistent with findings in the UK where rare newts and other amphibians as well as lizards, slow-worms and grass snakes make their last stands in these unprepossessing environs, among the trash, eroding pavements and ruined buildings. In fact brownfields turn out to be far more suitable habitat for these delicate little creatures than is the intensively managed agricultural landscape that has obliterated large tracts of Europes’s biologically diverse ‘Kulturlandschaft’.

stag beetle in Ailanthus stump At a Superfund site at the foot of Troy’s Ingalls Ave, I watched turkey vultures soar over an edenic looking mosaic of meadowy expanses that have cloaked the heavily contaminated soil. These neo-savannahs are punctuated by lush groves–a botanical mosh pit of weedy natives like box elder, black locust and cottonwood mixed in with exotic Ailanthus and Paulownia. All of this is gloriously unmanaged, left to its own rampancy, and though the species constituting this habitat are largely considered ‘invasive,’ they embody a new kind of ecological becoming, their novel juxtapositionings and processes of succession–a ‘Nature 2.0′ in the making.

If we put aside our purist bias, we might celebrate brownfields as territories of regeneration and marvel at how they adapt to the disturbances and wastes we leave in our wake. One might even regard them as ‘wilderness’ of a certain kind as they are one of the few ecological realms we have let slip from our control–leaving them free to reconfigure themselves and follow independent trajectories of neo-evolution.

Troy NY’s future brownfield rangers The collapse of industry though, leaves more than just picturesque ruins and novel habitat in its wake. For human communities,‘Detroitization’ means decaying infrastructure, diminished economic opportunity and the adverse health effects of pervasive chemical contamination. If sufficiently de-toxified, these lands can be rehabilitated as perfectly reasonable urban nature parks (see my previous posting on Berlin’s Templehof airport) but the challenge is to do so without diminishing their often surprising biodiversity.

Troy might be an ideal location for a Brownfields National Park, where local youth could work as ‘brownfield rangers,’ leading tours of the area’s ecological and historical heritage as well as doing field studies and cataloging the species to be found there. Though this necessitates a change of perspective in what we North Americans typically think of as a ‘natural’ park experience, it is high time we open our minds to such opportunities. Brownfields are the future. Brownfields are us!

Over on the other side of the continent, I met up with artist Marina Zurkow in Portland, Oregon. Together, we led artistic incursions into a Superfund site on the edge of the Williamette River. We explored first by water, using a flotilla of kayaks peopled by an intrepid collection of individuals who responded to our call for participation in what (to the less adventurous) might have seemed an arcane enterprise. We conceived our expedition as a kind of group imagination exercise and christened it -“IF YOU SEE IT–BE IT!” in the spirit of the biosemiotician Jacob Von Uexküll, who did such groundbreaking research on the spatio-temporal worlds of animals, which he termed the ‘Umwelt.’ Aboard our tiny craft, we collectively tried to imagine/channel what it might have been like to navigate the contaminated and disturbed riparian environment from an animal’s point of view (water striders, otters, sturgeons, etc.) – inhabiting (in our mind’s eye) their biosemiotic state, ‘becoming’ them, as it were, in a collective thought exercise.

Marina’s long term plan is to construct a raft-like roving laboratory she calls the Floating Studio for Dark Ecology, on which artists and researchers ply the river, exploring its narratives of contamination and recovery as well as disseminating practices of contemplation and engagement between its human and non-human communities.

Our early evening voyage proved suitably anthropocenic: a bald eagle gliding through the shimmering cottonwoods of Ross Island–a section of river whose bed is being continually scoured by heavy gravel mining machinery–the blue tarp and scrap lumber bricolage of homeless encampments festooning the banks of the Williamette–the third world within the first world, the metabolic waste of neoliberal capitalism as it eats its way through our material reality.

Neo-ecologies of Williamette Cove Once again there were fascinating and new ecological assemblage in these zones of dereliction and abandonment. Washed up on the industrial shore of a former shipyard–exquisite hydrozoans of a type I have never seen before:

hydrozoan The brownfields of the former factory site at Williamette Cove, though dangerously contaminated with heavy metals, wood preservatives and organic pollutants, proved not so ‘brown’ after all and were resplendent with novel botanical groupings–neo-succession! Native species like Arbutus menziesii (Madrone) formed habitat groupings with such hardy exotics as Paulownia tomentosa (princess or empress Tree) and Crataegus monogyna (European hawthorn). It is thought the empress trees made their original landfall in North America via their fluffy seeds, once used as a packing material for porcelain and other fragile goods originating in China and Japan. A gust of wind and an open crate at the dockside and their botanical colonization of the continent would have been begun.

In addition to brownfield neo-ecologies there is a parallel and equally fascinating neo-geology emerging from the material detritus of our age. Mineralogically, these are mostly composites and conglomerates or pyrolized residues of industrial processes such as coke and slag, as well as ceramics that have been fired into the form of brick, tile and pipe, much of it broken up into rubble. This so-called ‘urbanite’ is dominated by concrete and ferro-cement in various states of decay and petrochemically based asphalt and asphalt concrete, widely used in paving.

Sometimes though, a geologic object occurs that is of more obscure though still clearly anthropogenic provenance. At Williamette Cove, we came upon an exquisite specimen–a fossil of sorts–consisting of a fused mass of ribbed metal fragments, the armouring of industrial electrical cable, set within a matrix of a more indeterminate material, which might have been partially incinerated plastic. Perhaps this mystery mineral was formed when some itinerant metal collector tried to salvage copper wire by throwing scrounged cable into a campfire to melt off its rubber insulation and loosen the metal cladding. I may never discover this exquisite object’s true origin and it might well become the topic of frenzied conjecture to some future archeologist, wondering what our experience was like as we drifted deeper into the fraught and turbulent horizon of our anthropocenic future.

neo-geological form

where it all went down… The great blue bowl of the California sky has doubtlessly presided over some strange affairs, but perhaps none is stranger than the serial cycle of entrapment and petrification that started around 38,000 years ago in a collection of deceptively limpid ponds in what is now a quiet park in downtown Los Angeles. After it rains here, the play of sunlight and clouds is mirrored on their lambent surfaces, beneath which lies a menacing secret: for what first might appear to be a refreshing pool in an arid terrain is only a thin film of water obscuring an abyss of sticky bitumen, which has been oozing steadily from petroleum-bearing rock formations deep beneath the earth.

These are the notorious La Brea Tar Pits and since the days of the Pleistocene their peculiar configuration has served as both death trap and mausoleum for thousands of creatures–great and small, thirsty and merely curious–who venture into them and get stuck in their viscous pitch. Like a giant version of the ‘cockroach motel,’ once they ‘check in’ they never ‘check out’ and indeed the thrashing and bellowing of trapped victims attracts predators, whose natural wariness proves no match for the promise of an easy meal, ensuring they too are quickly doomed after jumping in for the kill. And so for thousands of years, whole conglomerations, entire food chains of animals have met their ends here: predators and prey sinking down alongside each other, each creature naïvely repeating the fatal mistakes of its predecessor: sabre-toothed cats and Dire wolves, with fangs and claws sunk into the contorted bodies of mastodons and camels, all of them frozen in elemental struggle as if in some Classical frieze. Not even the carrion eaters escaped the gruesome fate. Outsized vultures, giant condors and hideous, meat-eating storks, wheeling and squabbling for landing rights on the bloated corpses and almost corpses, snagged themselves when a carelessly extended talon or trailing pinion made contact with the merciless tar, that pulled them in, flapping and screeching , never to fly again. As well as being deadly, the tar has miraculous powers of preservation. The seething, interconnected beds of bone that have accumulated there have kept scientists busy ever since they first started excavating back in the early 1900s. Many of the rich paleontological finds are on display at the adjacent George C. Page Museum.

When I was a boy in Toronto back in the early 1960s, a small piece of the La Brea Tar Pits was on display in a dusty diorama at the city’s Royal Ontario Museum. This was a few years before the ROM adopted the loathsome trend for ’interactivity’, which consigned much of the museum’s extensive palaeontology collection to back rooms, out of public view, and what we got instead was an ersatz mishmash of mood lighting, audio tape loops and fibreglass models of dinosaurs standing aura-less amid plastic palm trees. Anyway before all that stupidity, I remember how transfixed I was ‘just looking’ at the thing itself, without being told how to think about what was in front of me – the tea coloured skeleton of a sabre-toothed cat, its outsized canines filigreed with tiny age cracks, poised to stab the neck of a hapless ungulate (a proto-camel? an extinct horse?) which had already begun to sink. It was the futility of it I remember the most, that both animals died together in the same inescapable way, the first doomed by thirst (or bovine idiocy), the second by carnivorous savagery. And I knew this scenario was to play itself out again and again because it was elementally and inherently unavoidable. Presiding over the sad scene was a tromp-l’oeil painted backdrop of a clot of vultures, hanging like wind-ripped umbrellas in the branches of a skeletal tree, and in broad brush strokes, a distant herd of mammoths melting into the horizon.

When I finally, this spring, got to tour the La Brea tar pits firsthand, I couldn’t help but see them as a kind of trope for contemporary times.

LA is a strange enough place to begin with–its palm-studded freeways and rivers of twinkling windshields pouring into the heat haze of the hyper- illuminated horizon–a place at once banal and startling, the High Baroque of American drive-thru suburbia amid scintillating beaches flooded in a golden, Canaletto-esque light. There are people there, of a certain age, whose faces have been so surgically altered it is as if they’ve been sucked through a magic wind tunnel. The mismatch between their wrinkle-less heads and the sun-withered bodies is chimerical, as if bands of Surrealist ‘exquisite corpses’ had gone AWOL, pulling themselves off the canvases and walking around. Los Angeles is the very essence of the American Anthropocene and yet prehistory bubbles and belches everywhere just beneath the surface. The city sits astride a massive oil field, where serried ranks of mini malls and tract homes lie nestled in the napes of brown hills and rustling eucalyptus groves, the edges of which bleed into a kind of terrain vague of ponderously nodding pump jacks tirelessly sucking petroleum out of a deposit dating back to the Miocene– a geologic epoch already long gone by the time the first mammoths sank into the tar.

Wandering through the pleasant grounds of Hancock Park, the past becomes the present and one soon encounters a pair of giant, chocolate-coloured ground sloths, like outsized Easter confections, placid and dim-witted in expression, yet armed with menacing fore claws that could easily rip the face off almost any attacker. As late as 10,000 years ago, these ungainly beasts lumbered across what was a vast North American range – their remains having been found from the Yukon to Mexico. At La Brea, they were regular victims to the suffocating tar.

yours truly and the ground sloths

In a still bubbling tar pit encircled by construction fencing, a family replica of gigantic Columbian mammoths replays a pathetic tableau. An adult is hopelessly stuck in the pit, its mouth agape in panic, its trunk frozen between the great curved brackets of its tusks, frantically gesturing to its mate and calf who stand helplessly on shore. The theme of serial entrapment and the futility of instinct gets amplified as soon as one enters the museum, which is packed with reconstructed skeletons and glass cases full of phylogenetically arranged remains, memorializing the legions of hapless creatures who died there over thousands of years, who just couldn’t stop themselves from making the same fatal mistakes over and over, in a senseless and recurring cruelty against which no benevolent god or Walt Disney narrator would intervene to warn ‘Stay out of those pits, yo!’ If only Spielberg had been in charge…

In paleontological terms, the tar pits are what is known as an ‘evolutionary trap.’ These create a stimulus that certain species are unable to resist and the results are often fatal. A contemporary equivalent has been the sad epidemic of dying albatrosses we’ve been seeing on Pacific Islands, their body cavities packed with bits of plastic that they seem programmed to snatch up from the waves and swallow in place of their natural food. Like the victims of La Brea, they just can’t help themselves.

Back at the Tar Pits, the Dire wolf (Canis dirus) seems to have been a particularly slow learner. To date the remains of over four thousand of them have been found there with doubtless many more to come. One of the more impressive displays at the George C. Page is a long, back-lit display, like something out of a high-end shoe store, containing hundreds of Dire wolf skulls, each an embodiment of one individual’s lack of impulse control. It seems that whenever a pack of them came upon an animal in distress in the tar, they would pile right on in on top of it, dooming themselves by their own overly developed killer instincts and susceptibility to peer pressure. The fact that the Dire wolf seems to have been exceptionally competitive, didn’t help matters. Males in areas where there was high population density developed outsized fangs with which to fight each other. It’s hard not to imagine the pack dynamic being a rather savage affair, especially when they chanced upon a bleating animal, trapped in tar. For the Dire wolf, there likely wasn’t a lot of time for second guesses. Though heavier and likely much meaner than their little cousin the coyote (Canis latrans), the Dire wolf failed to survive the Pleistocene, while the coyote still thrives in LA’s hills and canyons, feeding on what it finds in trash cans and snatching up unguarded pets. Though the Tar Pits weren’t the only factor in the Dire wolf’s continent-wide extinction, the evidence of its behaviour at La Brea indicates an inherent inflexibility, which must have been a major handicap in what, at the end of the Pleistocene, was a rapidly shifting set of conditions including changes in climate and the incursion of the first Paleo-Indians into its environment, who competed aggressively with the wolf for prey.

dire wolf skulls Though we may think our species’ ability to show foresight gives us particular resiliency–after all we started out in minuscule numbers, survived an Ice Age and proceeded to take over the world–we find ourselves now under a similar delusion to that which befell those hapless beasts at La Brea. Could it be that in the black, viscous materiality of petroleum we have finally met our match? Though we may think we have mastery over our fate, we seem blind to the possibility that it might be a substance that has control over us…

As an evolutionary trap– a nemesis–petroleum is the perfect agent. It is the very essence of death, a distillate of corpses from untold myriads of prehistoric organisms, which has quietly waited for us beneath the earth. If substances possess their own agency, as Jane Bennett surmises in her (2010) Vibrant Matter, is it so far-fetched to suggest that petroleum is luring us in, manipulating our innate behavioural vulnerabilities to ultimately absorb us into its oozing corpus? Like the sabre-toothed cat and Dire wolf before us, petroleum has exerted its ability to hypnotize, to communicate directly with our vulnerable animality, bypassing our much vaunted capacity for reason and discernment. It’s not that big a leap from the Tar Pits to the Tar Sands…

As happened to the Pleistocene creatures who got stuck in it when they put aside their caution, petroleum–ever protean– has set its exquisite trap for us in the form of a fata morgana, which gives us the illusion of eternally abundant and convenient energy with no long-term consequences. We are probably already in too deep to realize what has happened; that we are becoming petroleum, absorbed by the wily substance to become one with its subterranean deposits.

The Anthropocene might be remembered as a geologically brief period during which our species was allowed an overdraft, a blip during which we extracted a quantity of the black ooze before we had to repay our loan with the highest of interest; our lives, and those of the countless other organisms we took with us after we have made the planet uninhabitable. In so doing, we are offering up billions of putrefying corpses, untold tonnage of petrochemical garbage and entire landscapes of withered vegetation to be re-incorporated into the geologic, where unstoppable tectonic regimes will reprocess it into the mother of all oil fields.

So it is a mistake perhaps to wax too moralistic about our failure to rein in our natural impulsivity, to plan sensibly or imagine a future free from our addiction to this substance. Our connection to it might be too deep, too genetically encoded for us to resist through mere self critique.

Following the logic of the Dire wolf, our own species is competing increasingly viciously for what is (for the geologic moment anyway) a limited resource. The power elites in localities dependent primarily on petroleum production (Russia, Nigeria, Libya and others) have drawn whole societies into animality and impulsivity.

Even Canada, long a role model for liberal democracy, has slid into this petro-brutality. Under the prime ministership of oil-mad Stephen Harper, its government has declared a totalitarian war on scientists who study climate change and associated environmental contamination. The uncomfortable facts they keep bringing up highlight Canada’s abysmal record on these matters, which, aside from being an international embarrassment, threaten to push the usually complacent Canadians into a confrontation with the ecological Real (boring!, depressing!), invoking questions the Harper government is determined not to let us ask. Important and long-standing research facilities and environmental monitoring stations have already been shuttered, their scientists sacked and the scholarly material packed away or even thrown into the garbage. Those few scientists still working have been given STASI style minders, through which all communication with the public must be vetted. They even shadow the scientists at academic conferences to make sure they don’t say anything deemed ‘off message’ to the government’s single-minded agenda.

Yet given that our attraction to petroleum is demonstrably biological, can we really blame the individual oil worker, warlord or myopic Canadian bureaucrat? By doing their part to hasten mass extinction, they are in the service of the long term interest of petroleum itself. By extending its sticky tendrils through a higher dimensional space than most of us are letting ourselves imagine, petroleum assumes the characteristics of what the philosopher Timothy Morton calls a ‘hyperobject,’ an entire set of relationships, interactions agencies and desires of which we are but a small and transient part.

tar sands (via National Geographic)

dwarf birches and tundra  suddenly – reindeer!

The morning broke grey and brooding outside the Kilpisjärvi Biological Station and after a quick breakfast, we were on the trail, hiking up Saana Fjell, guided by Erich Berger of the Finnish Bioart Society. The idea was to familiarize ourselves with the geology, ecology and cultural history of the vicinity so we could dive into our research plans as soon as possible.

The Australian bio-hacker, Oron Catts had already been here for a week to do some scouting for his group’s ‘Journey to the Post-Anthropogenic’ project. They planned to perform a comprehensive bio-archeological survey of the crash site of a German Junkers 88 bomber that came down on Saana in 1942, which included a metagenomic analysis of the plane’s debris field and a recreation of the crash trajectory using a remote-controlled drone.

debris field It wasn’t long before we passed the tree line where the mountain birches gave way to an expanse of open tundra sweeping out before us in a swath of russet heath and exposed rock, with quivering patches of silver cloud here and there snagged on the crenellations of the topography. As if on cue, a small herd of reindeer appeared over the crest of a nearby hill and galloped across our field of view, cocking their heads as they past us and then just as quickly melting into the gloom of the opposite horizon. It is hard to judge distances here in this cold desert. An unusual rock formation in the distance might be small and quite close by or enormous and very far away.

I felt for a moment as if I had been transported back to the Pleistocene, as the landscape I was looking at was what much of Europe and North America would have been like at the end of the last Ice Age, though (other than the reindeer) there wasn’t any of the charismatic megafauna such as the woolly mammoth and the cave lions I would have had to concern myself with back then. Semi-domesticated, reindeer have sustained the local Sami people since ancient times and they are of the few creatures (other than snails) to manufacture the enzyme lichenase, enabling them to survive on lichen during the winter months.

How this delicate ecological balance will be affected by climate change is unclear but to my mind it doesn’t look good. Lichens exist in fairly specific temperature and humidity conditions and in Kilpisjärvi many are symbiotic with the birch trees, themselves a cold-dependent species. A continued warming trend in this region is bound to mean diminishment of suitable reindeer habitat. This has already occurred in North America, where the closely related Woodland Caribou has steadily disappeared from the southern portions of its range.

Standing in the middle of this iconic subarctic landscape, it is hard to imagine rapid changes occurring. For thousands of years, the processes shaping it have been gradual and incremental – the slow scouring of glaciers advancing and retreating, the infiltration of frost with its insidious heaving and splitting, the seasonal flows of meltwater into the lakes and rivers. The cold accentuates the sense of Deep Time here. Rocks dragged by ancient ice flows sit solemnly in place as if they stopped moving only yesterday. The sparse, slow growing vegetation is no match for the overwhelmingly geologic feeling of the place. Even minor disturbances stay visible for centuries.

But add even a small degree of warming and there would be potentially huge changes. Vegetative growth would ramp up, allowing trees to flourish in areas that were once windswept barrens. It is easy to imagine the slopes of Saana darkening as the Scotch Pine (Pinus sylvestris), now found only intermittently in the Kilpisjärvi area but quite common further south, finds conditions more suitable to it and becomes a dominant species. True tundra and the flora and fauna that depend on it could disappear from the area entirely.

lone Scots pine Fast-forward a little further and there could be a whole host of new species that find the once frigid environs of Kilpisjärvi newly tolerable. A good many of these are likely to be weeds, which thrive on man-made disturbance. Investigating the grounds around the research station, I soon found a small clump of English plantain (Plantago major) a cosmopolitan weed, dubbed the ‘white man’s footprint’ by North American First Nations, who noticed it growing wherever European colonizers had disturbed the original ecosystem. The humble plantain is just the beginning. I predict that larger weed species will soon be gaining a foothold at Kilpisjärvi; their seeds imported on tire treads or blown in with the wind.

I wondered how it might look here when Ailanthus altissima, a tree variously known as the ‘Ghetto Palm’ or ‘Tree of Heaven,’ moves into the Finnish subarctic. Originally from China, Ailanthus is exuberantly invasive, and has already moved into ruderal (ruin) ecologies throughout the world without any signs of stopping. This tree has the astounding ability to feed off concrete, allowing it to thrive in cracks in pavement, the roofs and facades of under-maintained buildings and pretty much any other place its myriad seeds are able to lodge themselves long enough to germinate.

Ailanthus trees As the global south becomes uninhabitable due to increasing drought, wildfire and relentless heat, it isn’t hard to imagine a newly temperate Kilpisjärvi becoming a major magnet for climate refugees, human and non-human. Higher annual temperatures, as well as attracting different flora and fauna, could make the cultivation of cereal crops a possibility and perhaps other kinds of intensive agriculture, now more characteristic of Central Europe. This could transform the wild, transhumance landscape into a ‘Kulturlandschaft,’ the subarctic wilderness giving way to ploughed fields, perhaps even orchards. There might be a property boom as the open range lands once suitable only for reindeer husbandry become hosts to cash crops and housing estates. The effect on the traditional Sami lifestyle would be incalculable.

A climate-changed Kilpisjärvi would be a kind of ‘hyperecology’– a co-mingling of adaptive, cosmopolitan weeds, perhaps a few resilient local organisms and a steady in-migration of biota from the south. Outside the national parks and reserves, post-climate change nature will have even less of a free hand. There is massive industrial development afoot for Lapland, particularly mining and its ancillary industries which threaten to blight vast tracts of the relatively pristine landscape with open pit mines, tailings ponds and processing infrastructure, which, as well as inevitably introducing all sorts of pollution will create a new terrain vague of slag heaps and factory wastelands. These ‘brownfields,’ ubiquitous in much of the industrialized world are the preferred habitats of the globally distributed ragamuffin flora: Ailanthus, Buddlea and Robinia, which find the toxic and impoverished soils to their liking.

Industrialized, intensely cultivated and densely populated, the Kilpisjärvi of the not-to-distant future might look strangely familiar to any present day resident of a more temperate latitude. Yet what has been predictable there for so long will soon become much more extreme. We may all find ourselves moving north.

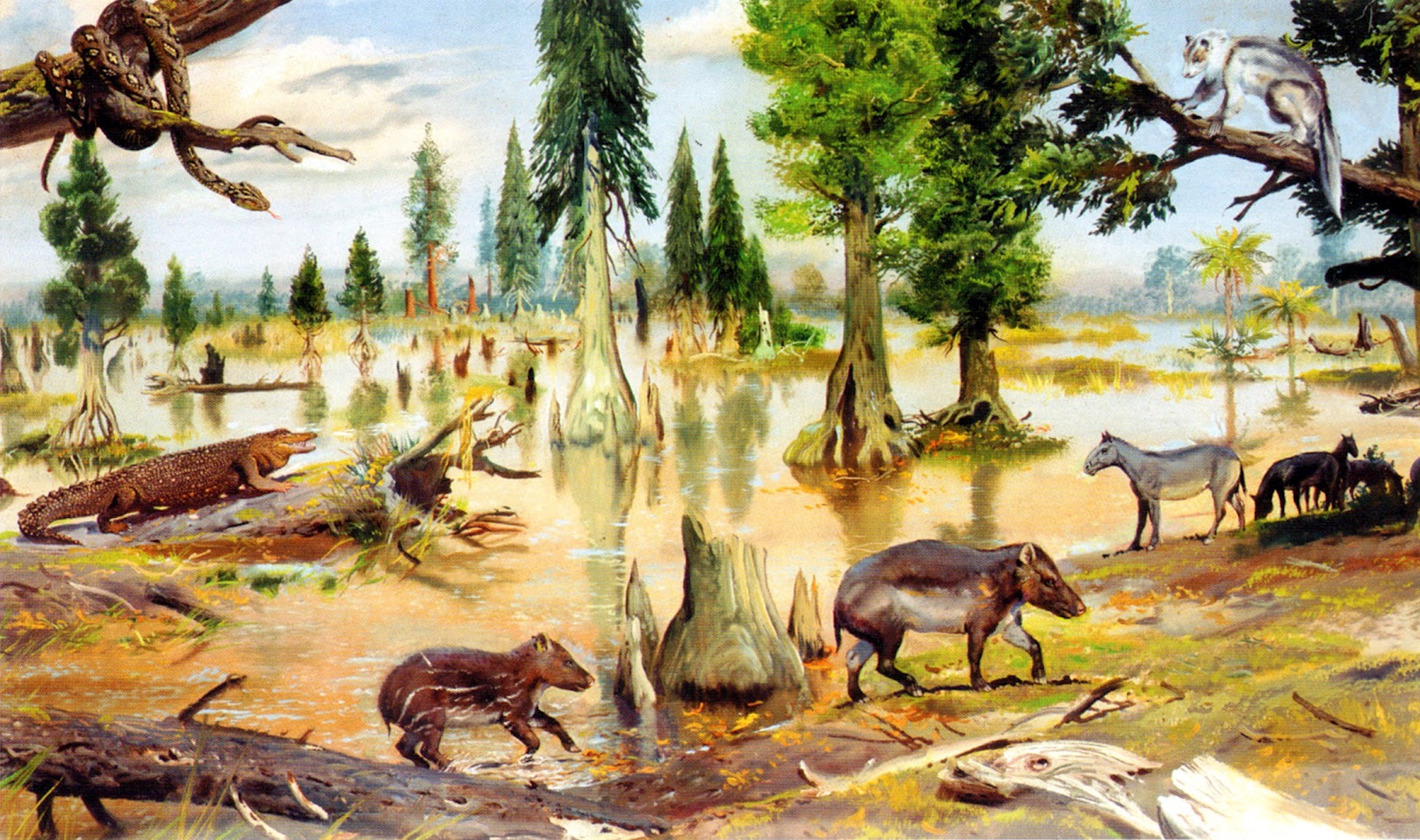

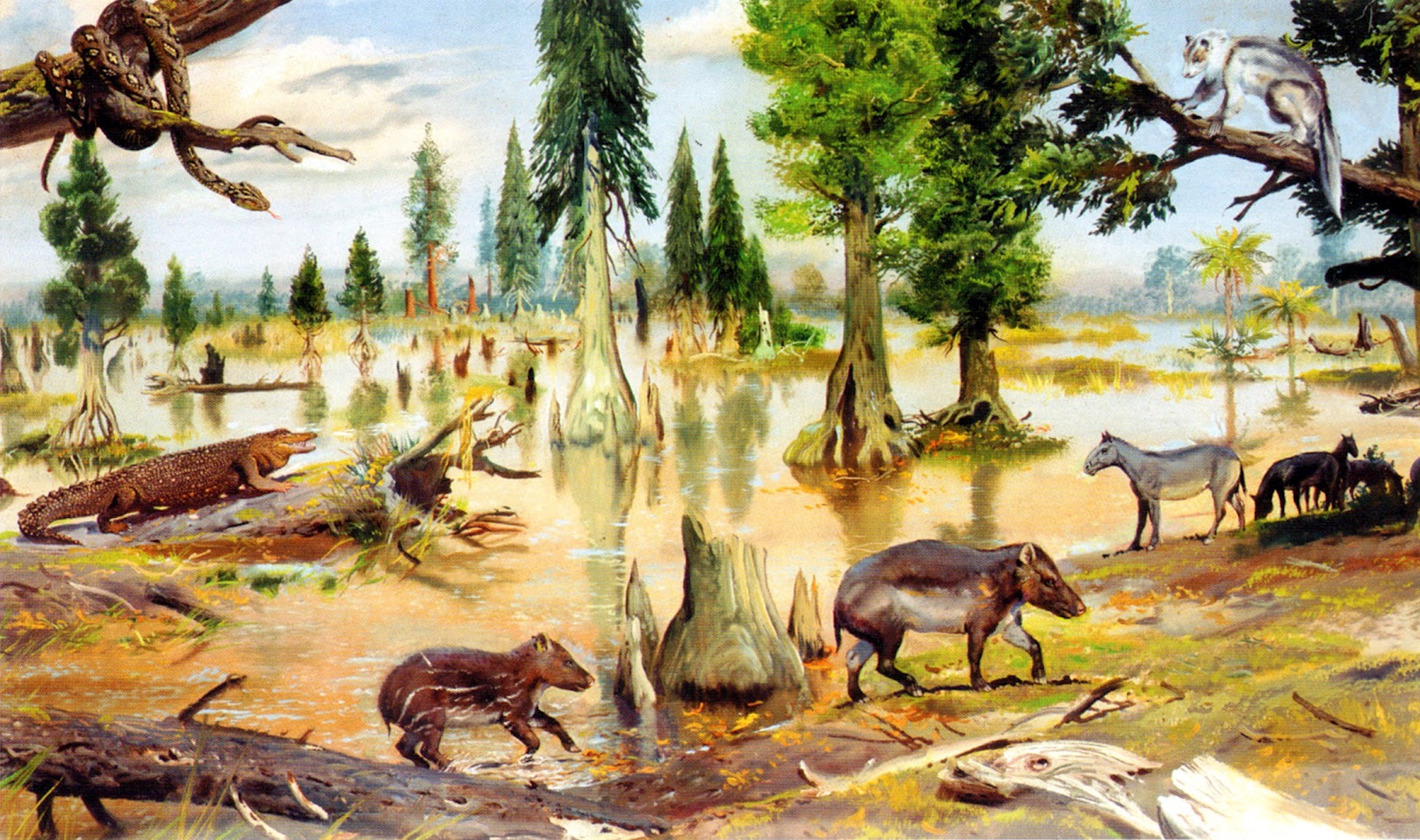

But climate change isn’t likely to stop at this arbitrary point. The heat will likely continue to build, especially if mankind continues dumping carbon into the atmosphere and particularly if the much feared ‘runaway greenhouse’ effect kicks in. What then for Kilpisjärvi? The Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum that happened some 55 million years ago gives us a clue. In those days, the weather north of the Arctic circle was sultry and humid the year round. In addition to the Sciadopitys trees I described in my previous posting, vast swamp forests of Metasequoia and Taxodium spread out across the far north of Eurasia and North America, with turtles and crocodiles plying through the black water and mire. It would have resembled the bayou country of Louisiana or subtropical China, with snow and ice pretty much non-existent, a far cry from the frigid Kilpisjärvi of today, which can be icebound 200 days a year.

Eocene landscape Northern regions are well on track for a repeat of these subtropical conditions according to the most agreed upon climate change models, which predict an up to 4 degree Celsius rise globally by the end of the century, with a strong likelihood that changes in high latitudes will be more extreme. Though the biota will surely be more impoverished than it was in the Eocene, not having had anywhere near as much time to evolve, an anthropogenically tropical Lapland would be a mind-boggling yet disturbingly real possibility.

Though our species’ effect on climate can (and will) precipitate far-reaching changes in areas like Kilpisjärvi, there are many planetary processes playing out over which we have no control. The evolution of biota over Deep Time is as much happenstance as forward movement, with periods of great flourishing such as the infamous ‘Cambrian Explosion’ interspersed with ‘reversal’ or mass extinction, either organically or extraterrestrially engendered, which often obliterate whole classes of once dominant organisms and provide opportunities for minor ones to come out of the wings.

Past instigators of mass extinction have included: asteroid impacts, widespread volcanic eruptions with concomitant ocean acidification, even the evolution of photosynthesis by cyanobacteria, which released the toxic gas oxygen into the atmosphere to the detriment of the once dominant anaerobes. Any and all of these scenarios will likely play out again somewhere in the fullness of Deep Time, but barring the elimination of all life on the planet, it is worth speculating on the impact such upheavals would have on the vegetated landscape.

For example, what would happen if flowering plants, also known as angiosperms, dramatically declined, perhaps taken out by some pandemic or selective evolutionary pressure? They’ve really only been common since the Cretaceous and it isn’t hard to imagine Kilpisjärvi’s abundant so-called ‘lower’ plants – mosses, club mosses and liverworts, moving into the vacuum and attaining gigantic proportions, as was the case during in the coal swamps of the Carboniferous Period.

Neo-Kilpisjärvi with giant club mosses A reduction in the availability of sunlight due to volcanic ash or widespread dust storms could have equally bizarre consequences. With green plants and algea in decline because of the challenge to photosynthesis, there would be a selective advantage for fungi, which might take over Kilpisjärvi forming bizarre, colossal structures as they did during the Devonian Period, some 400 million years ago, and again during the mayhem of the Permian mass extinction. Whether our own species would survive under such extreme and alien conditions is an open question, but life of some sort is almost certain to find a way. Perhaps fungi will regroup to form the planet’s supreme intelligence. Some would say, they already have!

It is this last point that gives me a vestige of hope. We Homo sapiens are a problematic creature, a classic, invasive species that thrives on disturbance, tends toward monoculture and displaces competing biota from its habitat. Yet in the overall scheme of things we are likely to be a transient phenomenon. We will either precipitate our own extinction, (and if the surviving ecosystems of the planet could sigh in relief, they surely would!), or we will find a way to live within our ecological means and develop a more equitable arrangement with the fellow denizens of the biosphere. My stay at the Kilpisjärvi Biological Station offered me the ideal vantage point to consider this conundrum. What we are in now is not so much of a ‘watershed’ moment but more of a ‘timeshed’ moment!

Neo-Kilpisjärvi with giant fungi

|

|